Tag: trade

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Podcast – #63 “The Bessent Gambit” (Posted 3/28/25)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – The Bessent Gambit (March 24, 2025)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

Before the election, there was a sense developing that suggested a major shift in how the US manages the global financial system. This vibe was described as the “Mar-a-Lago Accord,” suggesting the changes were similar in magnitude to historic events such as the Bretton Woods Agreement, Nixon’s closure of the gold window, and the Plaza Accord. In recent weeks, articles and podcasts have emerged which discuss some of the ideas that are percolating. In this report, we lay out the issues facing the US economy, Treasury Secretary Bessent’s plans to address them (at least what we know so far), the likelihood that these plans would be implemented, and the associated potential market ramifications.

Note: The podcast for this report will be delayed until later this week.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Podcast – #11 “Mineral Commodities in the World’s New Geopolitical Blocs” (Posted 6/6/22)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Mineral Commodities in the World’s New Geopolitical Blocs (June 6, 2022)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

For many years, we’ve discussed how the United States has been backing away from its historical role as global hegemon, setting the stage for deglobalization and a fracturing of the world into separate geopolitical and economic blocs. In our Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report from May 9, 2022, we provided a detailed, comprehensive forecast of which countries are likely to end up in either the U.S.-led or China-led bloc, which countries will lean toward one or the other, and which ones will try to be neutral. As a follow-up to that analysis, this report looks at the distribution of key mineral resources among those camps and what the different endowments might mean for geopolitics, the global economy, and financial markets in the future.

With China and Russia becoming ever more threatening from a military and geopolitical standpoint, and with the coronavirus pandemic demonstrating the vulnerability of supply chains even in peacetime, investors have become more sensitive to the security of commodity supplies and the way nations might try to monopolize or weaponize them. As such, we conclude with a discussion of the ramifications for investors.

Don’t miss the accompanying Geopolitical Podcast, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify | Google

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Podcast – #9 “Parsing the World’s New Geopolitical Blocs” (Posted 5/9/22)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Parsing the World’s New Geopolitical Blocs (May 9, 2022)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

For more than a decade, we at Confluence have been tracking and writing about the waning commitment of the U.S. to its role as global hegemon. We’ve shown how U.S. retrenchment and protectionism have helped erode globalization. Factors like deregulation, falling transportation costs, improved technology, and easing geopolitical tensions following the end of the Cold War may have promoted political and economic integration for decades. Now, however, governments across the globe are erecting barriers to trade, investment, and migration, leaving authoritarian strongmen emboldened to assert themselves. The latest example of that has been Russian President Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Amid these developments, we’ve argued the world will fracture into at least two main political and economic blocs: a U.S.-led bloc consisting mostly of liberal democracies and a China-led bloc of mostly authoritarian states. This report discusses which nations are likely to join each bloc, which will merely lean toward one bloc or the other, and which may try to stay neutral. Based on our predicted makeup of each bloc, we describe their differing political, economic, and financial characteristics. As always, the analysis also includes ramifications for investors.

Don’t miss the accompanying Geopolitical Podcast, now available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify | Google

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #69 “The U.S. Trade Deficit and Global Prices” (Posted 2/22/22)

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – The U.S. Trade Deficit and Global Prices (February 22 2022)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

When Democrats passed the CARES Act in January 2021, it was viewed initially as a political achievement. Polling from Politico/Morning Consult showed 75% of registered voters supported the bill three months after its passing. Meanwhile, Democrats began touting President Biden as the next Franklin D. Roosevelt. The legislation was so popular that the politicians who voted against the package started taking credit for it. However, the bill may have had an unintended consequence. The fiscal stimulus injected new money before the global economy was ready to absorb it. While domestic firms were sitting on low inventory, the pandemic prevented foreign firms from operating at full capacity. Thus, American desire for goods led to a rise in global inflation as firms could not provide the necessary supply to offset the demand created by the newly injected stimulus. Additionally, the trade deficit rose to an all-time high, as excessive demand led to an increased need for imports. In this report, we discuss how the CARES Act contributed to the widening deficit and a rise in goods inflation. We will also explain how we expect countries will seek to reverse some of the bill’s impact and conclude with possible market ramifications.

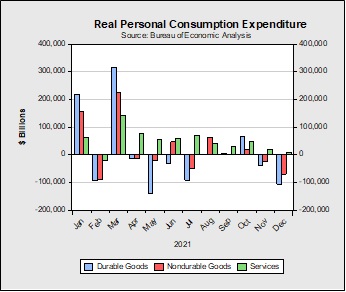

Following the passage of the CARES Act, Americans struggled to find places to spend their extra money. Because of pandemic-related restrictions, the availability of services was severely limited. In the first few months of 2021, restaurants hosted fewer guests, airlines offered fewer flights, and sporting events were, for the most part, uncrowded. With limited entertainment and travel options, consumers spent the bulk of their new money on durable goods. Last year, purchases of motor vehicles and recreational goods surged to levels not seen in the pre-pandemic era.

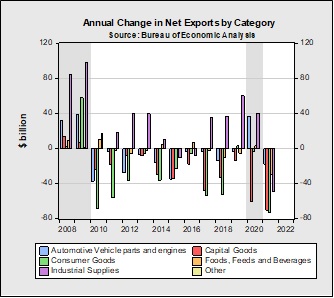

Robust spending in the first quarter of 2021 caught many firms off guard. In the previous year, when the U.S. went into lockdown, firms liquidated their inventories, believing the pandemic recession would be long-lasting. Rental car companies were particularly active because the lack of travel meant they would have to hold vehicles, a depreciating asset, on their balance sheets for an unforeseen length of time. Thus, these firms were motivated to sell their vehicles. The activity was so noticeable in 2020 that the U.S. recorded its first trade surplus in Auto Vehicle Parts and Engines since the Great Financial Crisis. The lack of available inventory carried by firms due to this selling activity contributed heavily to demand pressures seen in the following year.

Although consumers contributed to the jump in demand in Q1 2021, consumption data in March suggests firms also ramped up spending. Going into the Spring season, higher vaccination rates encouraged states to ease COVID-related restrictions. Consequently, firms expecting a travel rush, particularly in the Leisure and Hospitality industry, boosted spending on equipment and labor. This spending likely drove the rebound in durable goods from a lull in February to its highest level of the year in March. The aforementioned rental car agencies were big spenders during that time. The lack of available cars forced these companies to purchase used cars, something they typically try to avoid. Automobile consumption accounted for almost half of the total spending on durable goods in March. As a result, the price for new and used cars skyrocketed in 2021 and is currently one of the primary contributors to inflation.

While the U.S. was stimulating its economy, the rest of the world was still reeling from the pandemic. The difference in outcomes was likely related to the successful development and disbursement of COVID-19 vaccines. At the start of 2021, Americans found it relatively easy to sign-up and receive their first jab. Meanwhile, Europe found it difficult to distribute vaccines, Asian populations were vaccine-hesitant, and African countries struggled to even obtain vaccines. The emergence of the Delta variant made matters even worse. The new variant led to a surge in cases and severely hampered the efforts of countries to reopen their economies. Shipments were being delayed because ports were closing, and arbitrary quarantines resulted in constant labor shortages, and in some cases, factory closures. These pandemic-related disruptions meant foreign suppliers could not produce at levels sufficient to satisfy the U.S. demand for foreign goods. It had a negative impact on the global economy.

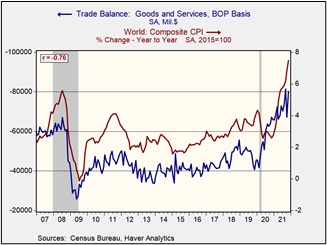

The combination of a lack of global production capacity and strong demand from the U.S. for inventories put upward pressure on the prices of goods and services around the world. The most noticeable rise in prices came from materials as demand for industrial supplies climbed sharply. Natural gas, steel, and crude oil were in exceptionally high demand because companies needed raw materials to ramp up production. Global demand for materials was so strong that the U.S. recorded its largest trade deficit for industrial supplies in at least 20 years, despite traditionally being a net exporter for that commodity group. Firms began looking at alternative sources for inputs, in some cases placing multiple orders with different vendors. In other cases, they were shipping inputs via airfreight as opposed to through ships. These orders may at least partially explain why firms, with the exception of automakers, are currently holding elevated inventory levels. Thus, much of the rise in the U.S. deficit for goods can be attributed to firms receiving multiple orders of the same goods from different suppliers.

U.S. demand for foreign goods may have pushed global prices upwards, but it will probably take a global effort to contain those price hikes. To combat rising worldwide inflation, we suspect that central banks across the world will start to tighten monetary policy. The rise in interest rates should relieve some of the demand pressure for goods and take some of the wind out of inflation. However, the primary driver of disinflation will likely come from countries easing pandemic restrictions and allowing firms to operate at full capacity. In the meantime, we think that conditions favor equities in the financial sector and commodities. Higher interest rates should make it easier for financial institutions to increase margins without taking much risk, and persistent demand for raw materials will probably continue to support commodity prices throughout 2022.