by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA, and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM ET] | PDF

Our Comment opens with an analysis of the market’s reaction to Nvidia’s earnings before turning to the ongoing negotiations between the US and Iran. We continue with a brief overview of the Cuban attack on a US-registered vessel, the White House’s push to advance the president’s retirement proposal, and our take on the Texas primary. We conclude with a summary of key economic data from US and global markets.

AI Uncertainty: Despite another strong quarter, Nvidia’s results did little to dispel lingering concerns about the AI trade. The chipmaker reported quarterly revenue of $68.1 billion, topping expectations of $66.2 billion, and guided to $78 billion for the current quarter, well above the consensus of $72.1 billion. The stock initially moved higher on the news but quickly gave back gains, underscoring persistent worries about the broader AI and semiconductor sector.

- The market continues to closely track Nvidia, whose semiconductors remain in heavy demand among the major players driving the AI boom. Investors view the company’s performance as a key gauge of capital expenditure trends across the industry. During the quarter, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta collectively announced plans to invest around $650 billion in coming years. The sheer scale of these commitments has become a central source of market anxiety over the sustainability of AI‑related spending.

- The shift in sentiment underscores a marked change in how markets view tech firms, from a “build, baby, build” mentality to a “show me the money” mindset. Investors, once content with ambitious growth narratives, are now scrutinizing the massive capital commitments big tech has made to AI infrastructure and other long-horizon projects. The focus has turned to how quickly these investments can deliver measurable, durable returns, especially amid rising political and regulatory pushback.

- Although Nvidia recently caught a break after the White House approved limited sales of some H200 chips to China, other tech companies may soon face fresh headwinds. President Trump is reportedly preparing to require major tech firms to pledge to supply their own energy for data centers. While this move could help defuse political backlash over the sector’s heavy resource usage, it would also likely push project costs higher by forcing companies to invest more heavily in dedicated power infrastructure.

- Given the significant demand for AI, which shows no signs of abating, and with optimism in the sector beginning to reaccelerate, the underlying growth story remains intact. However, this renewed momentum is accompanied by considerable uncertainty, suggesting that volatility will remain a defining feature of the market. In this environment, investors may benefit from adding selective international exposure to help balance regional risks and reduce concentration within their portfolios.

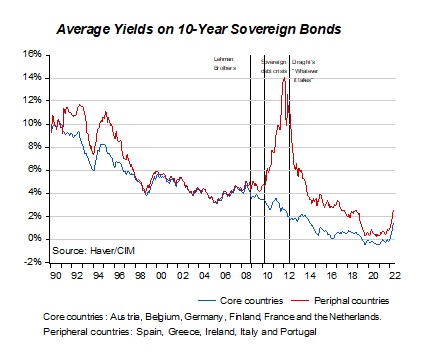

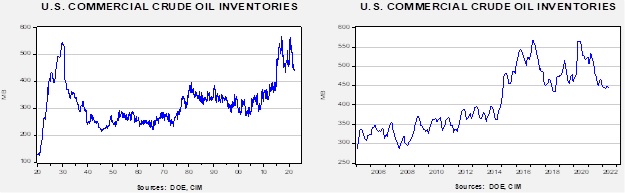

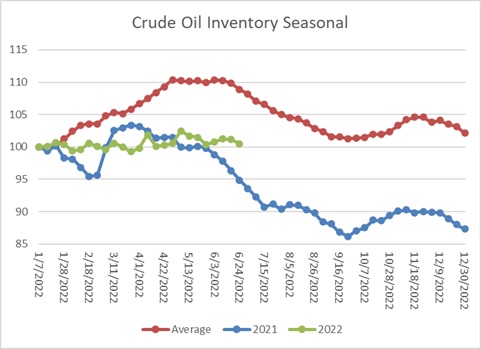

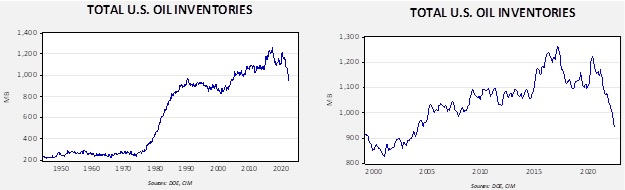

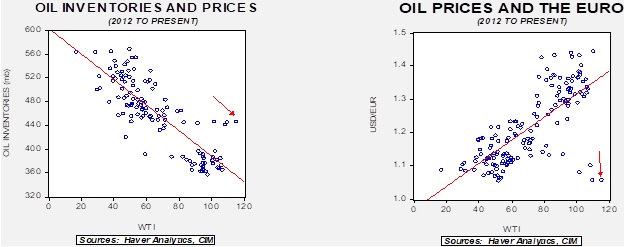

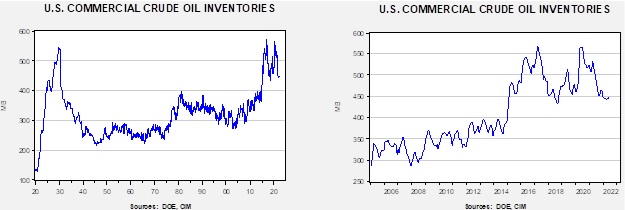

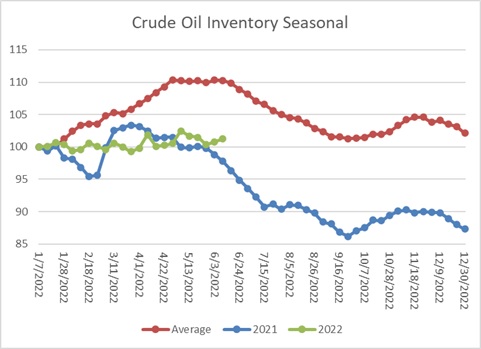

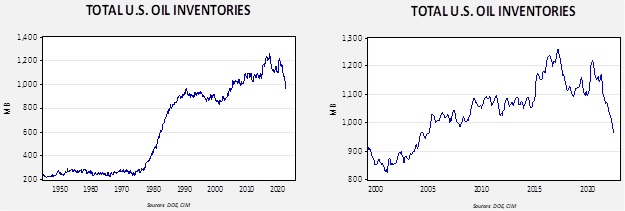

Iran-US talks: As the March 1-6 deadline for an agreement with Iran approaches, the two sides appear to be moving closer to a deal. Reports on Thursday indicated that negotiators were holding a third round of indirect talks in Geneva, with Oman acting as mediator. The discussions remain tense, with each side pressing for additional concessions while seeking to avoid open conflict. Financial markets have been closely tracking the negotiations to assess the likelihood of a broader war and its potential impact on asset prices.

- Going into the latest round of talks, Iran appears to believe it has already shown sufficient flexibility for a deal to be reached in the coming days. A representative of the Iranian delegation has reiterated that the country intends to maintain its uranium enrichment program for peaceful purposes. However, Iran is reportedly willing to make significant economic concessions, including potential investments in the US in areas such as oil, mining, and aircraft purchases, in an effort to secure an agreement.

- That said, the United States appears determined to secure as many concessions as possible and to ensure that any agreement has real staying power. US officials continue to press for limits on Iran’s ballistic missile program, despite Tehran’s resistance. Meanwhile, White House envoy Steve Witkoff has indicated that he wants any deal to avoid a “sunset clause” that would allow key provisions to lapse over time, a feature that was widely criticized in the 2015 Iran agreement.

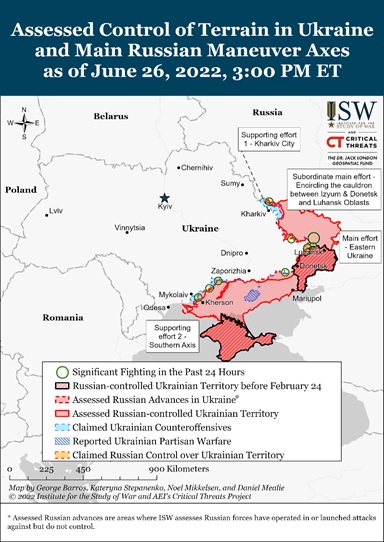

- Although talks are ongoing, there is a growing sense in the markets that conflict remains a real possibility. The United States has deployed more than 150 aircraft to bases in Europe and the Middle East, in what officials describe as the largest regional buildup since the 2003 Iraq war. At the same time, Iran has warned that it is prepared to retaliate both militarily and through asymmetric means, including potential cyberattacks, if it is targeted by a US strike.

- Our base case remains one of cautious optimism, assuming that geopolitical tensions ultimately will deescalate. Nevertheless, the risk of a direct conflict cannot be ruled out. In the near term, this backdrop is likely to favor commodity markets, supporting energy and precious metals. Conversely, meaningful deescalation would likely see that premium unwind, allowing prices to normalize. In this context, we continue to advocate for maintaining gold exposure in portfolios as a hedge against geopolitical uncertainty.

Cuba Strikes: Cuban forces shot and killed several passengers on a US registered speedboat headed for the island. According to Cuban security officials, the confrontation began when border patrol agents approached the vessel and the passengers opened fire. The United States has launched an investigation to verify Cuba’s account of the incident. The episode threatens to raise tensions between the two nations as the US continues to pressure the Cuban government into negotiations regarding its regime.

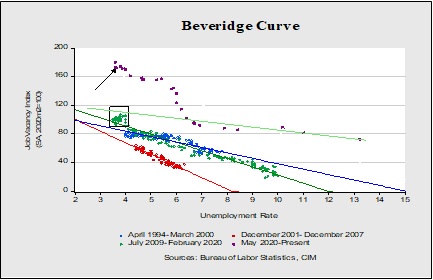

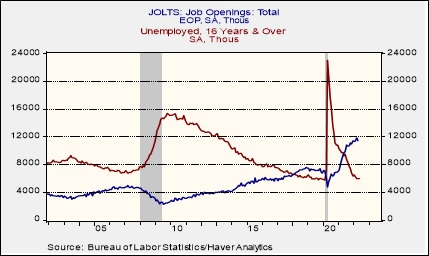

New Retirement Plan: US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent on Wednesday provided further details on the White House’s new retirement proposal. He indicated that the president’s plan to extend to all Americans access to the type of retirement accounts currently available to federal workers could be advanced through the budget reconciliation process, allowing it to pass the Senate with a simple majority. If enacted, the measure would likely expand market participation which could support equity prices.

Texas Primary: The largest red state is emerging as one of the most consequential Senate battlegrounds of the midterm cycle. Incumbent John Cornyn now trails Ken Paxton in the Republican primary, while Representative Jasmine Crockett leads State Senator James Talarico on the Democratic side. Cornyn would likely be favored in a general election, but a primary loss could suddenly put a traditionally safe Republican seat in play and reshape the broader battle for Senate control.