by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

Yogi Berra is famous for various quotes. He famously said, “Always go to other people’s funerals, otherwise, they won’t come to yours.” He also noted that, “A nickel isn’t worth a dime anymore.” The one we deal with most in asset allocation is the saying, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” But, as Hyman Roth remarked, “This is the business we have chosen.”

So, how do we make predictions? Our asset allocation process uses a committee approach and gives each member the freedom to create their own methodologies to arrive at their forecasts. This system has worked out reasonably well, in part because there is enough diversity of methods and opinions to cover a wide range of possibilities. From there, the committee comes to a consensus about the return, risk, and yield of 12 different asset classes.

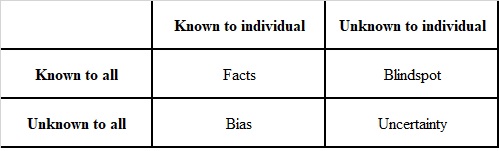

One way to examine this issue is to adapt a tool from psychology called the “Johari Window.”

This scheme was used by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld in his famous “known-unknowns” press conference. For our purposes, the “Facts” quadrant, quadrant one, is essentially history. This quadrant contains factual information—what we know is true. The second quadrant, “Blindspot,” is the area of known-unknowns. This is where we know a factor is important, but we don’t know what the outcome will be quite yet. This is the area of risk, where some degree of probability can be assigned. The other two quadrants are “Bias” and “Uncertainty.” Quadrant four, the uncertainty zone, is where we are not even aware of the outstanding risks. The third quadrant, the zone of bias, is where we think we know something but, in fact, we don’t.

To a great extent, quadrants three and four are where the problems lie. Of the two, bias is probably the most dangerous. This is the region of belief. John Maynard Keyes summed up this issue with the following quote:

Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.[1]

This is where narratives can dominate thinking and blind us to other possible outcomes. It is probably impossible to be a bias-free human. All of us carry self-evident truths that help us manage our lives. The key point is to be aware of them. One of the benefits of a committee structure, at least one with enough diversity, is that the bias risk can be offset by having “competing biases.” An even more effective committee can help each member become more aware of their individual biases as well.

Quadrant four, the area of the unknown, can only be divined by intuition. For the most part, this is the area where events haven’t happened before or occur so infrequently that there isn’t much history to work with. It isn’t impossible to predict these outcomes, but it isn’t easy. And, it is nearly impossible to get it right consistently. The history of markets is littered with analysts who were “one-hit wonders,” having made a great call once without repetition. A process in which multiple participants intuit the unknown at least offers the chance of a correct assessment.

Here is an example using the Johari Window with a current market issue. There is currently great concern about inflation. Here is what we know:

- Money supply growth is at record levels, up 25% on a yearly basis;

- The FOMC has changed its policy to end its primary focus on inflation control;

- Fiscal policy is expanding rapidly.

All these factors would support rising inflation risks. Offsetting these risks are:

- The bulk of cash remains on the balance sheets of the affluent;

- The U.S. economy remains mostly open, meaning that imports can help contain inflation;

- Household debt levels remain elevated and “scarring” from the pandemic will probably keep households cautious about spending.

So, what did the Asset Allocation Committee do, in light of these factors?

- We acknowledged the growing inflation risk well before the current situation. We have had an allocation to precious metals for nearly three years and have utilized bond ladders in portfolios with fixed income. We have also included an allocation to commodities for a year now.

- At the same time, given the distribution of cash, there is a chance that asset inflation could occur, at least in the near term. Price inflation will need less inequality. Thus, we are overweight equities.

- We also expect that policy will lead to a weaker dollar, and so we hold a sizeable allocation to international equities.

Essentially, Confluence’s asset allocation process attempts to take what we know and assess the quantifiable risks, based on history, consider what might happen that is uncertain, and make sure we don’t assume outcomes that may not be consistent with what we know.

[1] Keynes, John M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. (p. 383)