by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT]

It’s Monday in late August, the last one of summer. Global equity markets moved full circle overnight. Here is what we are watching:

The trade war: We were in the midst of writing Friday’s comment when China announced its retaliation against the most recent U.S. tariffs. This action was not completely unexpected. China had signaled that it would retaliate to the most recent tariff increase. However, it became clear that President Trump was incensed; in a series of tweets, he lashed out at China and the Fed. In what was perhaps the most momentous action, the president indicated that he planned to force U.S. companies out of China. The powers the president is invoking, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA), has generally been used for geopolitical events, not trade conflicts. However, even if the president can’t actually force companies to leave, the political pressure to draw down operations in China will be enormous. After the market closed on Friday, the White House announced additional tariff measures on Chinese goods, effectively putting levies on all Chinese imports. There were some voices suggesting that these actions looked a bit like the president was pulling his punches. Apparently, the president agreed with this analysis, indicating that he wished he had been tougher.

Equity market reaction on Friday was swift; stocks fell hard despite a rather supportive speech from Chair Powell. As is often the case, the White House does tend to be attuned to market developments and we have seen a series of comments designed to walk back some of the negativity. First, Economic Director Kudlow and Treasury Secretary Mnuchin both signaled that the president isn’t going to order American firms out of China. Second, the president stated that he got a call from Chinese officials indicating they wanted to talk, giving the impression that Beijing is caving. Chinese officials have disputed this account. This attempt to ease worries is a hallmark of this administration; they are clearly conscious of the reaction of various constituencies and react rather quickly to adverse feedback. Still, in the long run, it’s hard to make everyone happy.

Here is our take on the developments. From the time of Trump’s election, we framed his administration as a dynamic tension between the right-wing establishment and right-wing populists. The president won the election mostly because he ran as a populist, promising to deglobalize by restricting immigration, balancing trade and ending the offshoring of jobs. However, given his background, there was a case to be made that in office he would govern as an establishment figure, and he mostly did from the inauguration until February 2018. Regulations have been aggressively curtailed and taxes, especially on capital, were cut. He did keep pressing for a border wall and deployed restrictions on immigration. Although deglobalization was clearly a priority, it looked further down the list from the concerns of the establishment. Until February 2018, action on trade was mostly symbolic; there were tariffs on steel, but nothing broad. However, in Q1 last year, Trump began actively moving on broader sanctions on China and Mexico. Nevertheless, even with these moves, it was still difficult to see whether these actions were merely for show or if there was really a march toward serious trade restrictions.

China’s initial reaction to Trump appeared to be to offer small changes that would give the U.S. president actionable headlines, e.g., large purchases of grain. For a while, this policy appeared to be working. However, USTR Robert Lighthizer had bigger ideas. He wanted changes in China’s trade regulations that would be written into law, including intellectual property reforms. Last May, it looked like a deal was to be made. However, China made it clear that it would make promises but viewed changes to law as an infringement on sovereignty. China’s position is disingenuous—in general, trade law does restrict sovereignty and is really the essence of such law. Lighthizer wasn’t willing to accept that outcome; China decided it wasn’t willing to accept what it appeared to have agreed to, and relations have slowly deteriorated…until last week, when the deterioration accelerated.

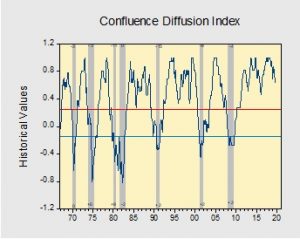

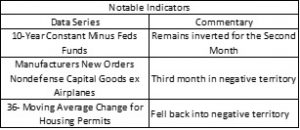

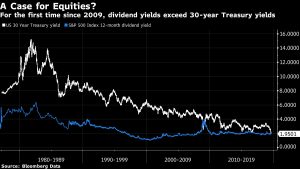

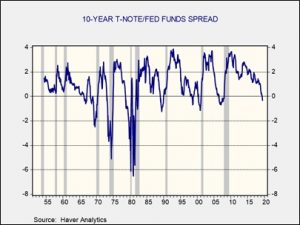

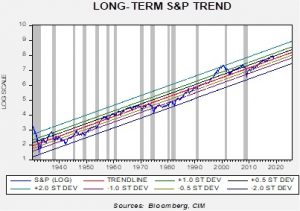

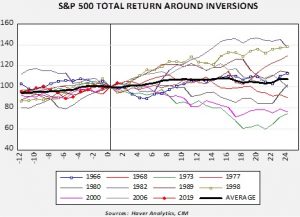

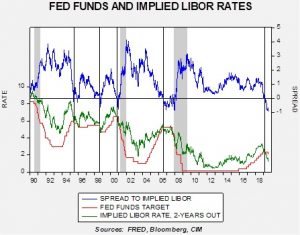

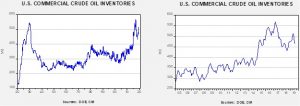

The recent yield curve inversions have led to analysis by strategists, including us, about the state of the economy and when a recession might occur. So far, the state of the economy is weakening, but still okay. However, as we thought about the situation this weekend, we were reminded that since the 1960s recessions have tended to have two sources, policy error (mostly monetary) and geopolitical events (1973-75, 1990-91). This escalation of the trade war may be putting us into the second category. The problem with the geopolitical recessions is that history isn’t much of a guide because each event is unique. The 1973-75 recession was mostly due to the oil shock—the rapid increase in gasoline prices shook consumer confidence. In June 1973, crude oil traded at $3.56 per barrel; by January, it was up to $10.11, at a 284% rise. Assuming $55 per barrel now, that would be like $156.19 per barrel in Q1 2020. In October 1973, the Conference Board’s consumer confidence index was 107.5; 15 months later, it was 43.2. The 1990-91 recession was triggered by the Persian Gulf War. Oil prices rose then as well but the fears about war reduced consumer confidence from 113.0 in December 1989 to 55.1 by January 1991.

Geopolitical recessions are tougher to time and, in the current case, there is still a chance of a resolution. However, we don’t see how either side can easily walk back the current turmoil despite today’s optimistic comments. The escalation of the trade conflict is increasing the likelihood of recession and, perhaps more troubling, is changing the calculus of estimating the downturn. In other words, obsessively watching for traditional signs of recession may be less effective if we are going to experience a geopolitically induced downturn.

Complicating matters is the notion that the president seems to believe that being tough on trade is a positive factor going into 2020. It might be, but winning reelection during a recession is a rare accomplishment, last done by Calvin Coolidge. It’s still not too late to pull back the trade issue, but trade restrictions do appear to be a core belief of President Trump. And, in his defense, the China issue does need some sort of resolution as the status quo was running out of runway. However, presidents who do hard things are usually not rewarded for their actions; President Carter’s appointment of Paul Volcker probably saved the U.S. economy but cost him the election. This is the risk that President Trump seems to be accepting.

So, where are we now? The remaining elements of the establishment wing of the administration, Mnuchin and Kudlow, are trying to keep trade talks in place and are talking up the economy. The populists, especially Peter Navarro, are pressing for greater confrontation. The president tends to vacillate between the two positions depending on his read of the political situation. So, uncertainty will continue, but this path may end up leading us into a downturn.

The G-7: This summit may go down in history as the one where it was no longer possible to paper over the differences between world leaders. President Trump was at odds with other members; President Macron, in a “stick in the eye” move, invited Iran’s foreign minister to stop by. Macron did give President Trump a “heads up” at a private lunch on Saturday afternoon. Still, the move by Macron could not have sat well with SoS Pompeo and NSD Bolton. PM Johnson got nowhere with the EU and now insists he won’t pay the £39 bn “divorce bill.” This G-7 meeting was clearly difficult, but that isn’t to say nothing was accomplished. President Trump indicated that a U.S./Japan trade deal is near completion. This announcement came after President Trump and PM Abe disagreed over recent missile launches from North Korea. In addition, France and the U.S. did come to a compromise on the former’s recent tech tax.

Jackson Hole: In addition to Powell’s speech, BOE Governor Carney made headlines calling for a new reserve currency to replace the dollar. The problems with having a national currency as the global reserve currency are nothing new. Keynes saw the flaw at the Bretton Woods meetings in 1944 and the Triffin Dilemma emerged in the 1960s. The problem essentially is that as the world economy grows, the demand for the reserve currency grows with it, forcing the reserve currency nation to constantly expand its current account deficit to supply the world with its currency. This widening current account deficit distorts the economy of the reserve currency and puts us in the position we are now—the drive to deglobalization is, in part, due to the demands of supplying the reserve currency. However, moving to a multi-lateral reserve base solves nothing; for the reserve system to work, some nation must be willing to be the global importer of last resort. Otherwise, there will be a lack of global liquidity. The U.S. was generally willing to play that role during the Cold War because it became part of the system of communist containment. However, the end of the Cold War and the massive expansion of China have put tremendous pressure on the dollar reserve system; the 2008 Financial Crisis was partly due to foreign nations dumping their saving on the U.S. financial system and demanding safe assets, which expanded mortgage lending.

Can a new system be developed? Only if global nations are willing to give up monetary sovereignty. The real solution is not a basket of currencies, but a global central bank that would manage the supply of the global reserve currency. The battle for control of this entity would be epic. Carney isn’t wrong in his concerns, but his solution won’t work.

Hong Kong: As the city’s ongoing anti-China protests turned violent again yesterday, Hong Kong police used water cannons against the demonstrators for the first time. In one skirmish, an officer even used his gun to fire a warning shot into the air. In the meantime, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam reportedly met over the weekend with a range of politicians, academics and business people who urged her to make concessions to the demonstrators, but there are no signs of such a move yet, and Hong Kong’s economic activity and assets continue to face headwinds from the situation. Of course, the Hong Kong economy also continues to suffer from weakening economic growth abroad and the U.S.-China trade war. New data today shows Hong Kong’s exports in July were down a sharp 5.7% year-over-year.

European Union: Officials connected with the European Commission are considering ways to simplify and soften the Eurozone’s government debt rules so that they put less pressure on countries struggling with an economic downturn. Although Italy isn’t mentioned as a reason for the move, the measure would likely help ease tensions between the EU and Rome. It could even help undermine the populist League party of Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini, which would probably be positive for Italian assets.

Middle East: It appears that Israel may be engaging in widespread attacks on Iranian proxies in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq. So far, Israel has only confirmed action against Syria on a base that Israel believes was launching drone strikes on its territory. What we may be seeing here is Israel taking advantage of Iran’s current problems caused by sanctions. Iran’s economy is under severe pressure from sanctions and this is undermining its ability to maintain its network of proxies across the region.

Negative interest rates: The use of negative rates, or NIRP, has been controversial, to say the least. Europe has been the most aggressive in deploying negative rates. For the most part, European banks have been reluctant to inflict negative rates on depositors, fearful of disintermediation and political repercussions. German politicians are considering legislation that would make negative deposit rates illegal. This is a profoundly bad idea. The most likely response from banks would be to simply refuse to accept deposits. Although the academic community is somewhat sympathetic to NIRP, in practice, it’s really a divine message that monetary policy is exhausted.

Mexico: The Mexican government reached a preliminary deal with four private energy firms to resolve a dispute over a major new natural gas pipeline from Texas to Mexico. Under the agreement, Mexico would no longer have to pay stepped up transport fees over time, as in the original contract. Instead, the transport fees would essentially be leveled. Mexico would pay higher fees for the first 10 years of the pipeline’s operations, but it would realize savings afterward. The deal is likely to keep concerns alive about the sanctity of contracts under the populist government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

View the complete PDF