by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT]

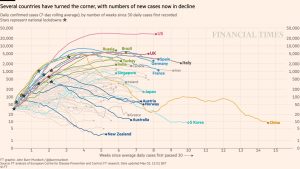

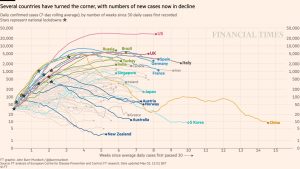

The risk-on tenor in the markets today reflects continued scientific progress against the coronavirus and further lockdown easing across the globe, although there are also worries that the easing might come too fast and spark a second wave of infections. Below, we review all the key virus news and related developments.

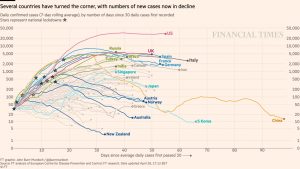

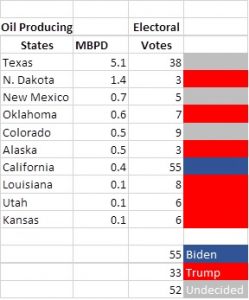

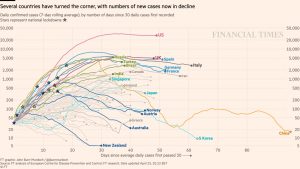

COVID-19: Official data show confirmed cases have risen to 3,603,217 worldwide, with 252,102 deaths and 1,174,006 recoveries. In the United States, confirmed cases rose to 1,180,634, with 68,934 deaths and 187,180 recoveries. Here is the chart of infections from the Financial Times:

Virology

- Hong Kong passed a crucial milestone of two weeks, or one full quarantine period, without recording any new, locally transmitted coronavirus infections, encouraging local leaders to continue loosening its relatively limited epidemic control restrictions.

- Under criticism for allowing inaccurate coronavirus antibody tests onto the market, the FDA will now require test companies to submit an application for emergency use authorization and show that the tests meet stringent precision standards.

- Currently, 13 tests on the market have received FDA emergency use authorizations, meaning they meet the agency’s standards.

- However, it’s important to remember that scientists still don’t know for sure whether or to what extent antibodies confer immunity from COVID-19.

- An online G20-backed pledging conference led by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen raised more than €7.4 billion for coronavirus testing, treatment, and vaccine research by the time it closed on Monday, even though major powers such as the United States and China declined to participate.

- Researchers have begun injecting healthy volunteers in the U.S. with four experimental coronavirus vaccine candidates in an effort to accelerate the identification of vaccines that work against the virus.

- Despite the apparent progress on getting control of the virus, continued lockdown easing in many countries and states have alarmed some medical and policy professionals, who warn that easing the restrictions too rapidly could spark a second wave of infections in the coming months. In an interview with National Geographic, top coronavirus official Dr. Anthony Fauci also called for great caution in reopening, warning that if given the opportunity, the virus will resurge.

Real Economy

- Even as Germany, France, Spain, and other countries in Europe continue to ease their virus lockdowns, the pace and method of easing the restrictions continue to generate controversy.

- Union leaders, politicians, and the wider public are often urging governments not to move too quickly.

- Pablo Casado, the leader of Spain’s center-right People’s Party, said he would not support Socialist Prime Minister Sanchez’s call for a two-week extension of the country’s lockdown, even though the lockdown is gradually being eased. Instead, Casado is demanding any extension in the state of emergency should be approved in legislation.

- Japanese Prime Minister Abe yesterday also extended his country’s lockdown for an additional two weeks.

- Rather belatedly, Saudi Arabia is finally ramping up efforts to support its domestic economy from the impact of the virus and the associated plunge in oil prices.

- In the U.S., even though the self-induced economic coma imposed to fight the virus has driven down all manner of asset prices and undermined activity, home prices have actually been rising. The reason: many sellers have taken their homes off the market during the crisis, crimping supply.

U.S. Policy Responses

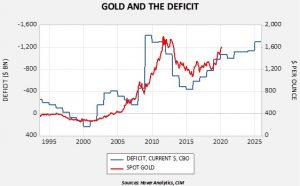

- The Treasury Department said it expects to borrow at least $4.5 trillion this fiscal year, up from $1.3 trillion last year, on account of the decline in tax revenues and increased spending related to the virus crisis.

- The department said it plans to issue $2.99 trillion in marketable securities in the second quarter alone, approximately five times the peak quarterly bond issuance during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2009.

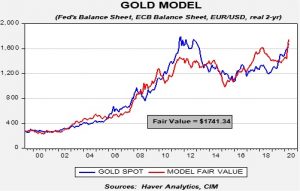

- As we’ve noted in previous analyses, burgeoning budget deficits tend to be associated with rising gold prices.

International Policy Responses

- Threatening the ECB’s massive bond-buying program, Germany’s constitutional court asked the institution to justify its purchases of public sector debt in recent years and warned it could block any new purchases of German debt if the ECB doesn’t respond within three months. The court also opened the door to fresh legal challenges against the ECB’s new €750 billion pandemic emergency purchase program, saying the earlier bond purchases were only acceptable because of various limits that have subsequently been eased under the new program.

- In its ruling, the court said the ECB needed to explain how it decided that the economic and fiscal effects of its bond-buying were proportionate to its mandated monetary policy goals.

- The European Court of Justice had approved the ECB’s quantitative easing program in 2018, sending the case back to the German court, but in today’s ruling the German court explicitly rejected the ECJ ruling as “inadequate from a methodological perspective.” That makes this another example of the EU’s faltering unity. If the case continues in its current direction, it could be a significant negative for European fixed income and equities.

- EU Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton said the virus crisis shows the need for Europe to bolster the resilience of critical industrial supply chains in sectors ranging from pharmaceutical ingredients to raw materials used in advanced batteries, adding to the evolving policy momentum toward deglobalization.

Political Fallout

- Just days after President Trump threatened to impose new tariffs on China in retaliation for sparking the virus crisis, and after U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo claimed he has evidence that the coronavirus escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin and Deputy National Security Advisor Pottinger on Monday offered assurances that there is no plan for punitive action against China.

- Although there has still been no official Chinese reaction to Pompeo’s accusation, Chinese state media angrily accused him of “spitting poison” and lying.

- U.S.-China recriminations over the virus are a negative for the financial markets because they could complicate the effort to get the global economy working normally again after the crisis subsides.

- As evidence that the Japanese may also be looking to blame China for the coronavirus, graffiti calling for all Wuhan residents to be killed was found on the wall of a restroom at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo.

Iran: The Iranian parliament has approved currency reform that will slash four zeros from the country’s currency to help ease the psychological impact of soaring inflation. Under the reform, every 10,000 rials will be swapped for one unit of a new currency known as the “toman.”