Author: Rebekah Stovall

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Meet Fumio Kishida (November 8, 2021)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

Whenever a big, rich country gets a new leader, there could be potential investment implications, and Japan is no exception to this rule. When former Prime Minister Suga announced last summer that he wouldn’t seek reelection as head of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, the first step in Japan’s political transition to a new leader was the party’s vote in mid-September naming former Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida to take over as LDP chief and, upon a later majority vote in the Diet (Japan’s legislature), as the head of government. Facing a legal deadline to hold new elections by the end of November, Kishida called for the next ballot to be on October 31. Now that the LDP has won that election, giving Kishida a full four-year term as prime minister, it’s a good time to review his background, leadership skills, and likely policies going forward. At the end of this report, we also explore the likely investment ramifications as Kishida takes power.

Asset Allocation Weekly – #60 “Is Monetary Policy Affected by Financial Markets?” (Posted 11/5/21)

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Approaching a Traffic Light in Germany (November 1, 2021)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

Germany’s parliamentary elections in late September were momentous for several reasons. Perhaps most important, the elections set the stage for a new leader to take power as Chancellor Angela Merkel decided not to stand for another term after leading Germany since 2005. However, even though the retiring Merkel is likely to see her left-of-center rivals take control of the country, the coalition they’re forming may leave Germany’s key economic and financial policies relatively unchanged, with big implications not only for Germany itself but also for the broader European Union.

In this report, we parse Germany’s party structure and discuss how past coalitions have run their economic and financial policies. We next focus on how those economic and financial policies have played out in Germany and beyond during the 16 years of Merkel’s rule, and why the current coalition talks may leave many of those key policies in place. We conclude with a discussion of the investment ramifications if that turns out to be the case.

Asset Allocation Weekly – #59 “The Debt Ceiling & the Platinum Coin” (Posted 10/29/21)

Asset Allocation Weekly – #58 “The Inflation Adjustment for Social Security Benefits in 2022” (Posted 10/22/21)

Asset Allocation Quarterly (Fourth Quarter 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

- Although we expect the recovery’s rapid pace of growth to slow markedly, we believe the probability of a recession within our three-year forecast period is low.

- Supply shortages, labor issues, and their attendant impact on inflation are expected to abate over the next 12-18 months, leading to our expectations for inflation to eventually settle within the Fed’s threshold.

- The combination of aggressive monetary accommodation by the ECB, fiscal support across the continent, and solid GDP growth in the U.K. provides a favorable backdrop for European equities.

- Equity allocations among all strategies remain elevated with the retention of a heavy tilt toward value and, where risk appropriate, an overweight to lower capitalization stocks.

- The high allocation to international stocks remains intact given our expectations for overseas growth.

- Risks emanating from China lead to the elimination of emerging market positions in most strategies.

- Commodity exposure is retained with gold being employed across the array of strategies for the advantages it affords during heightened geopolitical risk.

ECONOMIC VIEWPOINTS

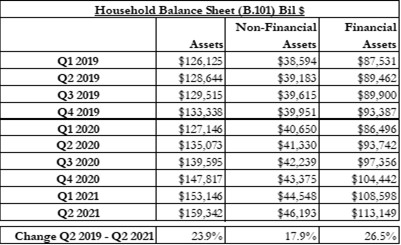

Our expectations for growth through our three-year forecast period are tempered by supply chain rebuilding, labor issues, a less accommodative Fed, and an uncertain path for ratification of an infrastructure package. Although we expect the economy to move from recovery into expansion, it likely won’t be in a linear fashion. Rather, the drumbeat of Fed tapering, a surge in retirements, supply shortages, and fiscal intransigence will create quarterly fits and starts in the economic progression. With regard to retirements, it is notable that policy accommodation has helped boost both financial and real asset prices since the beginning of the pandemic-induced lockdowns over 18 months ago. This rise in asset prices has made it easier for baby boomers to retire.

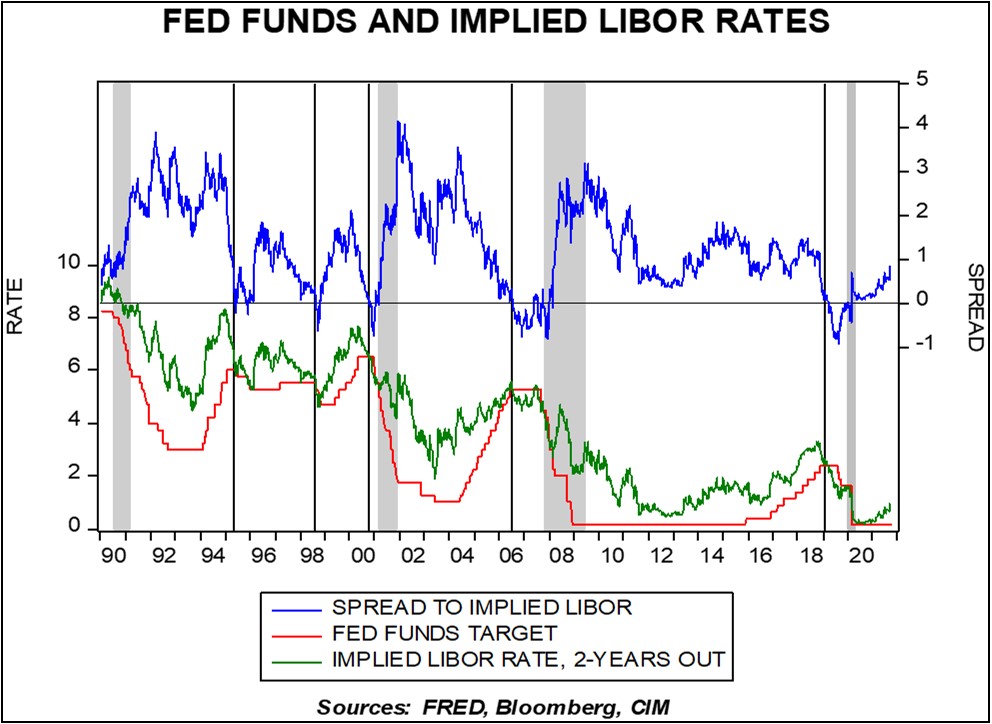

A sizable segment of the working population has found it economically feasible to retire, adding to labor pressure across virtually all sectors and industries. Against this force of labor is Fed monetary policy that will likely belatedly deliver needed discipline by normalizing policy. Though tapering of the aggressive $120 billion monthly balance sheet purchases of Treasuries and mortgages may well be concluded by this time next year, we believe an increase in the fed funds rate will be delayed. While the recently released dots plot indicates an earlier rise, the forecasts were made by a roster that has seen more changes than most college basketball teams. The known and potential departures on the FOMC underscore the increased probability of a Fed that leans toward a continued dovish policy that will delay a rate increase as long as possible. Although elevated numbers of retirees plus the ongoing pandemic would suggest deflation, the monetary accommodation by the Fed, crimping supply chains, and healthy household balance sheets not only offset deflationary pressures, but may support a rate of inflation persisting above the Fed’s 2% target level for the next 12-18 months, especially when including the more volatile segments of food and energy. The implied LIBOR rate, two years out, indicates the market’s anticipation for the Fed to begin raising rates. It is worth noting that, in most instances, the market’s expectations precede the Fed’s initiation of tightening by at least several quarters. Although the number of observations can hardly be characterized as statistically significant, this measure is the confluence of all market participants and, therefore, indicative of the broad range of expectations.

From a global perspective, the IMF recently cut its global growth forecast modestly for 2021, from 6% to 5.9%, due to the continued supply/demand mismatch in global supply chains. Despite this change, the IMF maintained its 2022 outlook with a moderation to 4.9%. Global central banks are responding differently to inflationary pressures as Brazil, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, and South Korea are among those that have already engaged in monetary tightening, while the ECB and BOJ are expected to maintain aggressive accommodation. While most expect recent inflationary pressures to subside, the uncharted nature of the pandemic has most policymakers on guard if inflation expectations prove to be more material. Adding to the economic dilemma are issues in China, inclusive of the property woes and saber-rattling toward Taiwan. Both issues heighten geopolitical risk. However, amassing U.S. and global elements into our forecast, we find that while the variability of outcomes is broad, the potential for recession within the next three years is low, albeit greater than zero.

STOCK MARKET OUTLOOK

Over the near term, we expect equities to fare well as earnings growth continues, liquidity remains abundant, and investor sentiment is elevated. As a result, the relatively high allocations to equities are preserved this quarter. Beneath the veneer of the overall equity complex, we find a divergence in prospects among sectors in the U.S. The ability to navigate through supply constraints and pass higher prices onto consumers will likely favor lower capitalization companies as dexterity should be rewarded. In addition, more cyclically oriented companies have historically proven to have greater resilience during bouts of inflation, even during abbreviated periods such as we expect to unfold over the next 12-18 months.

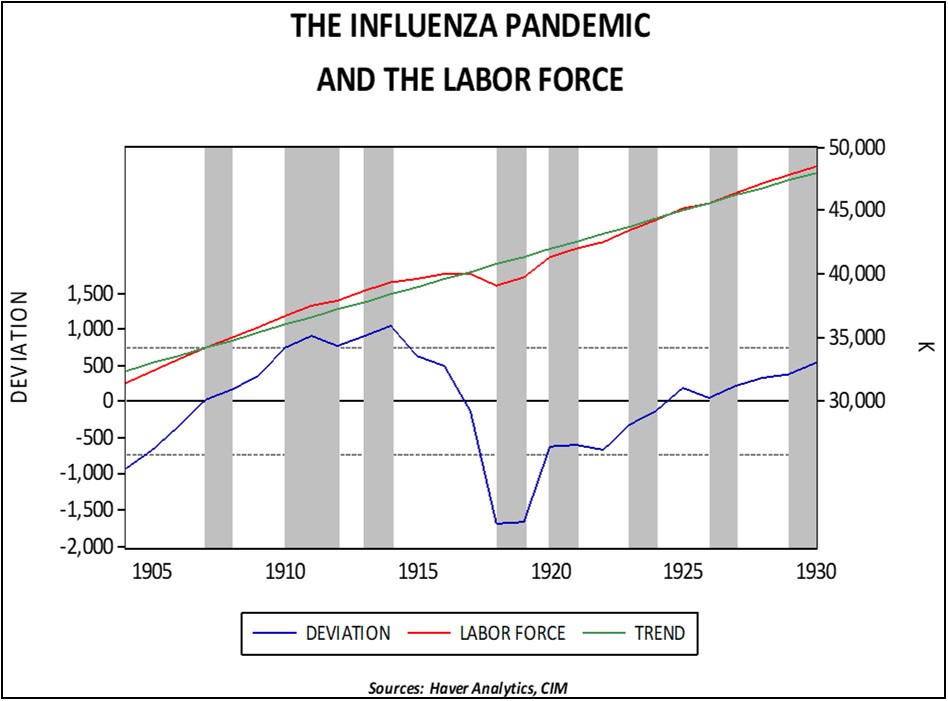

Longer term, the outlook is more indeterminate. Though the prior statement usually goes without saying, given the range of potential monetary and fiscal policy responses to labor, supply, and possible inflationary pressures, it carries even greater gravity over the next three years that compose our forecast period. Regarding the first element of labor, the analogue from the 1918 pandemic provides a level of comfort that a full recovery is probable, yet will probably evolve over several years. Similarly, the supply constraints should be resolved and help dampen the third element of pricing pressures on goods and services. However, the potential exists for lower fiscal support and even reactionary tightening of monetary policy toward the end of the period, which could lead to a decline in investor sentiment. Moreover, as the labor force recovers, aggregate labor costs could increase to the point of dampening corporate earnings. These aspects conspire to encourage some restraint on equity risk. Consequently, the heavy tilt toward value remains as does the U.S. large cap sector overweights to Materials, Industrials, Financials, and Housing.

Although global economies are experiencing the same supply chain issues and inflationary effects as the U.S., the ECB and BOJ appear committed to aggressive monetary accommodation. On the fiscal side, changes in government in Germany and Japan add some questions to their respective fiscal policies. Regardless of who they choose as leaders, they are expected to continue to provide fiscal support to their economies. While lagging the U.S. by several months in their fight against COVID, Japan and especially Europe appear to be well into their economic recoveries. In the U.K., the elimination of COVID restrictions has led to solid GDP growth. While the potential exists for a rate increase by the BOE prior to year-end and trade issues with the EU may continue to grow, corporate health is solid. Within emerging markets, however, the advantages many might have as they emerge from their fight against COVID are overshadowed by concerns surrounding China. Not only does China account for at least one-third of popular broad emerging market indices, but it wields significant influence on other emerging economies, particularly in the Pacific Basin and Latin America. Even ignoring the geopolitical risk engendered by its increasing pressure on Taiwan, China’s slowing growth and real estate market difficulties may have contiguous effects. Due to our views on developed markets, in general, and Europe and the U.K., in particular, the allocations to developed markets remain high, with overweights to the U.K. and Europe in strategies where it is risk appropriate. Emerging market exposure is eliminated in all strategies except Aggressive Growth, where the remaining investment excludes mainland Chinese equities.

BOND MARKET OUTLOOK

As noted above, our expectations call for the Fed to conclude its balance sheet tapering prior to increasing the fed funds rate, which we believe will be later than many market participants anticipate. A plausible consequence is that the Fed will be viewed as being reactive, causing yields to rise as inflation becomes seen as stickier rather than “transitory,” leading to an intra-period steepening of the yield curve. Nonetheless, our expectation is that inflation will prove less than durable owing to the eventual increases in the fed funds rate, resulting in a relatively flat yield curve by the end of our three-year forecast period. Among credits, over the course of this year, spreads on both investment-grade and speculative-grade debt have ground tighter. However, as noted in the Stock Market Outlook, we anticipate that labor issues could lead to margin compression toward the back-end of our forecast period which could translate into higher borrowing costs and a resultant widening of spreads for investment-grade corporates and especially speculative-grade bonds. Regarding mortgage-backed securities [MBS], the spread versus Treasuries is fairly tight and not particularly attractive for the environment we envision. Consequently, MBS are excluded and we have an overweight to Treasuries in the taxable strategies where income is an objective.

OTHER MARKETS

Although traditional segments of the REIT complex have recovered over the past quarter, particularly office and retail, the variance of valuations between the traditional and technology segments remains wide. While we expect the traditional segments should continue to recover, valuations ascribed to warehouses, data centers, and cell towers may restrain returns. Therefore, our expectation for REIT returns over the full forecast period are roughly equivalent with the expected dividend yield. As a result, REITs are employed solely in the Income strategy for the varied source of income they provide.

Commodities continue to be included across the array of strategies. Albeit slightly restrained, our expectation for global economic recovery encourages an allocation to a broad basket of commodities, with an emphasis on energy. Gold is retained as a potential haven given heightened geopolitical risk emanating from a number of domiciles and especially from China.

Keller Quarterly (October 2021)

Letter to Investors | PDF

Before I begin to tap on the keyboard and write these quarterly letters, I always pick up the last few letters to remind myself what I recently wrote. I don’t want to appear ignorant of past comments, nor do I want to ignore a prognostication that proved to be incorrect. As I perused the last letter (July 2021), I was struck by how little had changed from an investment viewpoint, despite the torrent of news over the last three months. How could this be?

From a real-world economic perspective, we are seeing empty shelves in stores, prices rising for a host of items (especially commodities), and millions of jobs unfilled, leading to higher labor costs. In non-financial news, the COVID delta variant continues to be a problem, the crisis of the Afghanistan withdrawal shocked many, we have legislation that can’t get passed, our taxes may be going up, and the debt ceiling crisis is back (now kicked down the road to December 3).

That’s quite a list of turmoil, and it’s merely a partial list. These items are very important to most Americans. But these things have less of a negative impact on the long-term value of stocks and bonds than you might think.

Let’s address a few of these items. The COVID delta variant has been a big problem over the last three months. As I wrote last quarter, it appears to be more contagious, but less lethal, than the original variant. This doesn’t mean it isn’t very dangerous; it is! But it has proven to be manageable for the nation as a whole, given the arsenal of vaccines and treatments available. The result is that the early-reporting delta variant states saw their cases, hospitalizations, and deaths peak in late August. Nationally, cases, hospitalizations, and deaths appear to have crested in September. These peaks were lower than the COVID peaks we saw over the last winter. This is important from an economic perspective because the progress of the economy is inversely proportional to the lethality of COVID. As COVID recedes, and we expect that it will, the economy moves forward. This is good for jobs, incomes, corporate profits, and (ultimately) the stock market. This progress is not in a straight line, but it is moving forward.

We are certainly in an era of shortages and rising prices. This has logically led many to believe inflation will become a problem (especially those baby boomers, like me, who began our adult lives during the very high inflation years of the 1970s). Such shortages are common after a deep recession, such as the recent one. Production halts and truck driver shortages have played havoc with supply chains, particularly in a world of just-in-time inventory management. No one seems to carry just-in-case inventories anymore. Perhaps they will from now on. Empty parts bins and empty retail shelves are all part of the same story. While this is frustrating for all concerned, one must remember that demand exceeding pandemic-constrained supply isn’t all bad. The key is that demand is there. We would have much more trouble if demand was tepid relative to supply. Our experience is that such recession-induced supply problems work themselves out over time, usually in a year or two. I’d be surprised if this problem is still acute a year from now.

The labor situation is similar. There are millions of job openings not being filled. A major cause is that millions of older Americans have apparently decided to leave the labor force and retire. This has caused cascading labor dislocations and shortages everywhere. Is this bad? In some ways, yes. But it is a sign of economic strength, not weakness, that our economy is demanding more jobs than can be filled. The price of labor (wages) will eventually move up in response to the supply/demand imbalance. That may or may not produce higher inflation, but it is almost certain to produce higher incomes for those that are working, and higher incomes are good for consumer demand, the engine of our economy. In turn, that is good for American businesses and stock prices.

As for the government, an inability to pass laws has never been bad for stocks. Managers of businesses like the “rules of the game” to stay the same over time. We’re in a mode right now where the bills we’re likely to see come out of Congress are not expected to be as bad for business as was feared just a few months ago. Yes, Congress may raise taxes. There’s no way to spin that as a positive for stocks and bonds, except (once again) that what is likely to emerge from Washington isn’t as bad as we feared just a month or two ago.

In a nutshell, the world remains an unpredictable place, full of turmoil and tragedies, yet the overriding factor here in late 2021 is that the worldwide economy continues to emerge from the COVID-induced recession of 2020. In fact, last quarter, U.S. GDP exceeded peak GDP just prior to the recession. That means our economy is no longer in recovery but is now in expansion! I’ll bet you didn’t hear that on the news. Good news just doesn’t sell. But it does register in the financial markets. We continue to be optimistic for the remainder of 2021 and 2022.

We appreciate your confidence in us.

Gratefully,

Mark A. Keller, CFA

CEO and Chief Investment Officer

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Revisiting Thucydides (October 18, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

The Thucydides Trap is an idea that comes from the ancient Greek historian of the same name who described a situation where the incumbent superpower of the time, Sparta, was faced with an insurgent power, Athens. The two powers ended up in a ruinous war. Thucydides postulated that when an established superpower is being threatened by a rising one, the likelihood of war increases.

Graham Allison did a study of the trap[1] in 2017, examining earlier examples but focusing on the situation between China and the United States, which appears to have at least some of the same characteristics that Thucydides outlined in his History of the Peloponnesian War that led to the conflict between Athens and Sparta. Allison, as noted above, was primarily concerned about the potential for war between China and the U.S., but he also analyzed 16 other historical rivalries and concluded that 12 resulted in war while four did not. Obviously, this ratio is not comforting. Allison did conduct an examination of the trap conditions that didn’t result in war and tried to draw conclusions, but the concept of the Thucydides Trap has become a model for examining the U.S./China situation.

However, Hal Brands and Michael Beckley are proposing something of a twist to the trap. They don’t dispute that the odds of conflict rise when there are rising powers that threaten the existing power arrangement. But their position is that it isn’t exactly true that a rising nation is the problem. Instead, what leads to war is if the rising power perceives that its rise is slowing. They call it the “peaking power trap.” They argue that the real problem arises when an insurgent power begins to fear that its acceleration is slowing and thus the perception that a window of opportunity is closing is what produces war.

In this report, we will examine the idea that China may be reaching such a deceleration and therefore perceives that time is no longer on its side. If that is the case, there may be no better time than the present to move quickly to secure its geopolitical goals while it has the power to achieve them. The analysis starts with a review of the concept of the “high growth/low cost” (HG/LC) producer and the risks that emerge when that phase comes to a close. We will also include a discussion of population issues. From there, we will examine China’s geopolitical constraints and its capacity to overcome them. Finally, in the section on market ramifications, we will look at how these two issues combine to potentially raise the problem that Brands and Beckley have introduced.

[1] Allison, G. (2017). Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.