by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] Happy employment Friday! We cover the data below, but the quick take is that the report is mixed. The drop in the unemployment rate to 3.5%, a new cycle low, is impressive. However, wage growth for non-supervisory workers fell to 3.5% from 3.6%, and the growth rate for all workers fell rather markedly to 2.9% from 3.2%. The headline payroll number came in at 136k, a bit below expectations. The data has triggered a risk-on trade, with interest rates rising amid stronger equity prices. Here is what else we are watching this morning:

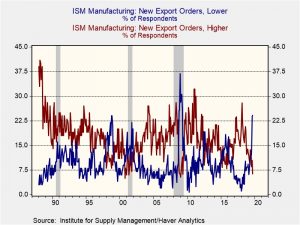

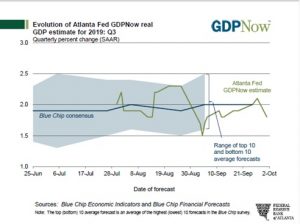

The economy and the Fed: Yesterday’s ISM services data came in soft and added to concerns that the economy was coming under pressure.

This index is generally a coincident indicator and doesn’t signal recession until it crosses 50. It also doesn’t have a long history, but the data is clearly in a downtrend. Unlike the manufacturing index, the exports portion was a bit weak but most purchasing managers were reporting steady export orders. Unfortunately, the subsector that showed the most profound weakness was employment, which has fallen from 56.2 in July to 50.4 in September.

Weaker economic data is raising expectations that the FOMC will accelerate rate cuts. Vice Chair Clarida seemed to support this notion. Hopes of easing likely led to yesterday’s equity market recovery. However, the drop in the unemployment rate (see below) will make it hard for the Phillips Curve faction of the FOMC to agree to a rate decline.

Brexit: PM Johnson’s plan for the Irish border fell with a thud in Brussels. Although there hasn’t been an outright rejection yet, it is unlikely that the plan as it is currently constructed would get all 27 nations to agree. Johnson has suggested he is open to other concessions but it isn’t obvious if they would be material. Meanwhile, Johnson is working on Parliament to see if they will approve his exit proposal. He might be closer than one would think. To pass, there are three groups he needs to win over. First, there is the matter of the 21 former Tories who he kicked out. He needs all of them. He needs all 9 DUP members. To get over the line, he needs some defections from Labour. There are a number of Labour MPs who come from Leave boroughs that might vote for Johnson’s plan. In fact, this is the primary reason why Labour has not actually taken a position on Brexit; the party is divided, and Corbyn would lose MPs if he elects to support Remain. If Johnson can get his deal passed and the EU rejects it, it appears to us that the U.K. will leave on Halloween.

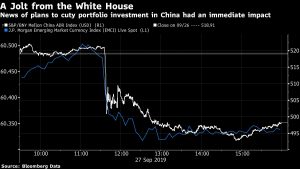

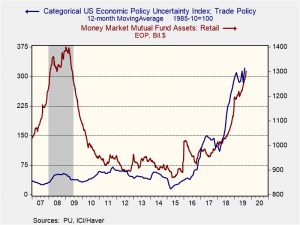

Next week’s trade talks: In light of market weakness, there is some speculation that the administration will at least agree to a truce. That would entail a postponement of tariffs and at least a jump in Chinese agricultural imports. However, a postponement without anything on intellectual property would look weak and it would be hard for the Trump administration to accept. Additionally, China views the U.S. as an unreliable negotiating partner because, from their perspective, the administration changes its position after a deal has been made. This charge is not exactly fair; instead, we suspect there is a high level of “strategic ambiguity,” where both parties say the same thing but mean something quite different. In reality, we don’t think either side is willing to make the concessions necessary to make an arrangement but neither wants a “blow up” either. There is also a narrative that Xi may simply wait out Trump and hope for a more compliant administration in 2020. Beijing may want to rethink that position.

Masks off: Carrie Lam will make it illegal to wear masks at protests. We doubt these measures will have an immediate effect, but it will make it easier for the government to arrest protestors who otherwise will be vulnerable to tear gas.

Israel: Prime Minister Netanyahu has agreed that if he is able to form a unity government with opposition leader Gantz, and if he is then indicted for bribery, fraud and breach of trust, as is widely expected, he will retain his title but give up his powers to an “interim premier.” The coalition negotiations are currently deadlocked, but the deal could help move things forward.

India: The Reserve Bank of India slashed its benchmark short-term interest rate to a nine-year low of 5.15%, from 5.40% previously. That marked the fifth rate cut in a row as the economy has slowed due to heavy corporate debt on weak consumer confidence. In fact, the RBI also cut its forecast of economic growth in the year ending in March 2020 to 6.1% from 6.9%.

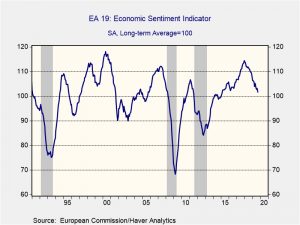

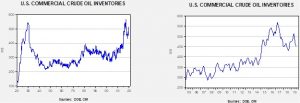

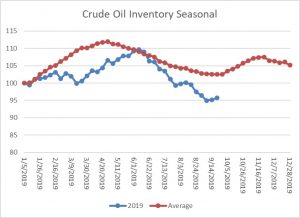

Odds and ends: Civil disorder has developed in Iraq. Although it appears to be driven by opposition to widespread government corruption, such unrest can be co-opted by outside actors (read: Iran) to disrupt oil flows or to mask attacks in the region. Although the situation in Kashmir has not been in the news lately, warnings that the conflict could escalate have been issued, cautioning that the problem could go nuclear. EU migration commissioner Avramopoulos warned that “irregular” crossings from Turkey into Greece are on the rise again. That raises fears of a new immigration crisis that could give nativist, populist parties renewed energy despite recent signs they may be on the wane. The risk of renewed political instability would likely weigh on Eurozone stocks and the EUR. Finally, we are monitoring the impeachment inquiry, but until it has a direct effect on the financial markets our commentary on the issue will be limited.