Daily Comment (September 18, 2019)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT]

Markets are stable this morning after a wild day in the overnight lending market. The Israeli elections did not yield a clear result. The FOMC meeting concludes today. Here is what we are watching this morning:

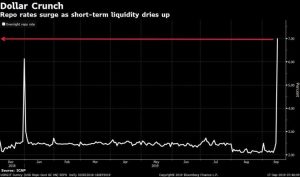

The funding problem: We have received many inquiries on the state of the money markets. Yesterday, the money markets were roiled by an apparent funding shortage which sent repo rates soaring.

Bids for fed funds reached the 5% level, well in excess of the upper limit of the fed funds target, currently at 2.25%. For the first time since the onset of QE, the New York FRB conducted overnight repo operations; the NY FRB was authorized to purchase up to $75 bn of collateral to inject cash into the system with about $58 bn being drawn. In an unsettling development, the “plumbing” didn’t work initially, and the operation was delayed by about 25 minutes. The fact that this facility hasn’t been used in over a decade is probably the reason for the delay; it’s possible that a number of people on the NY FRB’s desk had never been involved in such an operation.

However, before we jump into all of that, a bit of history is in order. The Fed used to routinely intervene with repurchase operations before the financial crisis. When banks were in the settlement period at the end of the month, banks with excess reserves would lend them to other banks that were lacking. Occasionally, spikes in fed funds occurred; around holidays, a bank somewhere would find itself short of reserves and by the time they came to the Fedwire, most banks were closed and the ones that were not could lend at a penalty rate. Usually, the next day, the Fed would conduct repo operations to buy securities and put liquidity back into the system.

Then QE happened, and the traditional way that money markets operated was changed. The banks were flooded with reserves, so the Fed could no longer guide the policy rate by adjusting the level of bank reserves. Instead, it began paying interest on reserves and that Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER) rate became how the policy rate was set. There is no incentive for a bank to lend reserves below that rate, so the IOER has become the effective floor for interbank reserve lending.

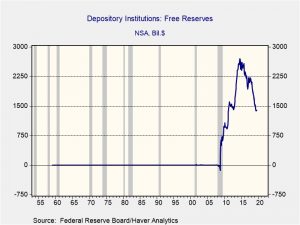

Free reserves are total reserves less required reserves and other borrowings from the Federal Reserve. Other borrowings are very small, so, for practical purposes, free reserves are excess reserves. As the chart shows, excess reserves in the banking system are $1.386 trillion. So, at first glance, it seems odd that a shortage would develop.

Here is what we think is happening:

- Perhaps the most interesting part of this issue is the inability of entities to turn securities into cash. Essentially, that is what a repurchase agreement (repo) is. This sort of transaction is the lifeblood of finance. When entities would rather have cash than earn interest on that cash, that signals a problem.

- As the charts above shows, there are ample reserves in the aggregate banking system, but there seems to be a problem of serious maldistribution. It appears the major banks are holding the bulk of the excess reserves and seem unwilling to lend them. The big banks complain that they are holding these large reserves due to regulation. Given that regulators have a goal of making the large banks safe, the banks seem content to hold high levels of cash and earn IOER, which is currently around 2.10%. Even with the possibility of risk-free profit at unusually high spreads, banks with reserves did not rush in to take advantage of the spreads. This means (a) they are inept, (b) they need the reserves more than the profits or (c) they don’t trust the counterparties. We lean toward “a, b” but if “c” is the issue, we have a bigger problem.

- The major media is reporting that a combination of tax payments, Treasury borrowing and other liquidity draining activities were the proximate cause of the shortage. Although these events probably contributed to the cash crunch, the amounts don’t seem strikingly large. Thus if these were the culprit, available liquidity is really tight and the Federal Reserve has a serious problem and needs to start re-expanding the balance sheet.

- An overlooked factor in all of this is dollar strength. Even though the dollar is excessively valued relative to inflation, and in some cases, unit labor costs, the dollar continues to be buoyed. Although the spreads against other nations’ interest rates are usually trotted out as a factor supporting the dollar, the persistence of dollar strength appears to be more like a dollar shortage. In other words, foreign borrowers that have financed in dollars are struggling to acquire dollars to service debt. A side issue is that the attack on Saudi Arabia may have played a role as well. Usually, the KSA funnels around $400 mm per day into the U.S. money markets from oil sales, but with the sudden halt in oil production, it is highly possible that the kingdom is actually doing repos to generate cash to meet its dollar obligations.

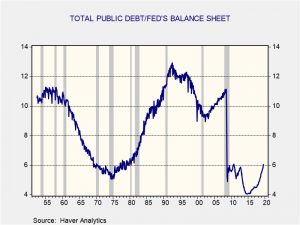

- The level of Treasury debt/Fed’s balance sheet has fluctuated over the years but has ranged between 6x to 12x. After QE, the ratio plunged to about 5x, and has fallen as low as 4x. However, the combination of rising Treasury borrowing and a shrinking balance sheet have pushed the ratio to a bit more than 6x. The historical record would suggest this is not an alarming level, but it is possible that in our current environment, the ratio may need to be below 5x for the money markets to have enough liquidity. In other words, the world changed after 2008 and the Fed doesn’t know for sure what are the proper level of reserves. However, it is looking rather obvious that they are too low.

- Another thought. Over the past four decades policymakers generally have relied heavily on monetary policy to guide the economy. Discretionary fiscal policy has been used occasionally, but only in emergencies when presidents can prod Congress to act. The problem with monetary policy is that it works through the financial system and its primary tool of stimulation is lending, with refinancing being secondary. However, if the real problem is excessive debt, monetary policy is simultaneously helping and exacerbating the problem. It’s a bit like a drunk trying to postpone the hangover by continuing to accept cocktails. At some point, the debt must be addressed; it’s the job of the political system to assign the cost of adjustment. What policymakers would likely prefer is to use inflation and financial repression to force the adjustment on creditors over a long glide path. Although, inflation can’t be triggered by monetary injection alone (yes, Milton Friedman was wrong); inflation needs reregulation and deglobalization to work, and financial repression needs reregulation of the financial system to force savers to accept negative real rates. We believe this process is underway, but progress is very slow (the last time we dealt with a debt overhang was the Great Depression and it wasn’t really resolved until we had the fiscal expansion with war spending). In the meantime, events may preclude addressing the debt overhang at a measured pace.

- So, bottom line, should we be worried? Yes, but it is hard to figure out what exactly to be worried about. It is difficult to see how we are on the cusp of a domestic banking crisis. As noted above, banks seem to have plenty of reserves. Fear itself, along with zealous regulation, may be prompting reserve hoarding and that may be exacerbating the problem. But, for whatever reason, there appears to be a dollar shortage and the Fed can address that by reflating its balance sheet. It probably will also be more aggressive in repo operations, perhaps even establishing a standing facility. However, these events suggest that even though the overall economy may not necessarily need lower rates, the financial system is in desperate need of cash and the Fed, as the global lender of last resort, should probably be cutting rates more aggressively. Still, given the Fed’s history, they don’t tend to act on these “plumbing” issues until a crisis develops. We will continue to monitor this issue and will be the first to admit that it is devilishly complicated. Nevertheless, two things do stand out; first, caution is warranted and second, the Fed should get aggressive in easing. A historical analog might be the 1998 LTCM crisis; Greenspan made a sharp emergency fed funds cut to flood the money markets with dollars. It prevented a crisis but it probably led to the last upleg in the tech bubble in equities.

FOMC: There is no doubt the Fed will cut rates by 25 bps today. Everything else will probably disappoint. We doubt the dots will signal further easing this year and we expect at least one dissent from the KC FRB. Additionally, the press conference will likely be non-committal; do not expect any clarity on the aforementioned money market issues in the presser. If we are right, the yield curve should flatten, gold will ease, equities will likely ease.

Oil: The KSA says it will return to normal production levels by the end of the month. We think this claim is wildly optimistic; we would expect, at best, 2.0 mbpd to 3.0 mbpd by the months end. Both the U.S. and the KSA seem to believe that Iran is behind the attack, but seem reluctant to assign blame. That’s because doing so will require action and neither the Trump administration nor the KSA seem to want a war with Iran. BREAKING: PRESIDENT TRUMP INDICATES HE WILL INCREASE SANCTIONS ON IRAN. This decision shows his deep reluctance to engage Iran militarily. This reluctance may encourage Iran to become even more aggressive.

Hong Kong: Protestors are increasingly pressing the U.S. to support its movement for democracy. The White House has mostly been non-committal; if the president intervened in the situation, it would likely end any chances of a trade deal. However, that isn’t stopping Congress from getting involved. House bill 3289 has been introduced, titled the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act of 2019, would force the executive branch to judge if the two systems program is being upheld, and direct the White House to take action if China is deemed to have undermined Hong Kong’s democracy. It is highly unlikely this will pass, but it does show that this issue could become a complication in trade negotiations.

Spain: The country will hold elections again on November 10th as Pedro Sanchez was unable to form a coalition government. This will be the fourth election in four years, and highlights a political problem seen across Europe; deep divisions in society are making nations nearly impossible to govern.