by Bill O’Grady and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EST] There is much to discuss this morning. Let’s get to it:

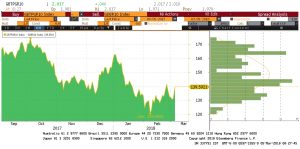

Cohn out: Gary Cohn, Director of the National Economic Council, resigned yesterday evening. Although reports suggest he has been considering the move for a couple of months, the proximate cause was the inability to turn the president on tariffs. The financial market reaction was swift—equity futures plunged after the announcement, although they have regained some of their initial decline.

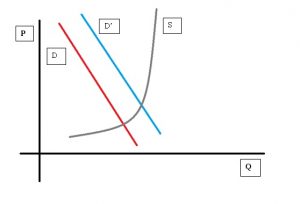

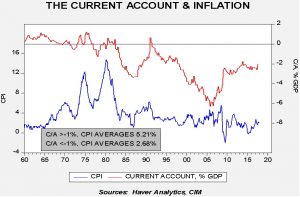

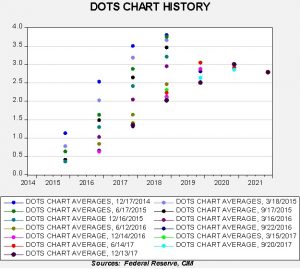

At this point, the broader market reaction has been rather scattered. A turn to protectionism is, over time, inflationary (using the structural/cyclical model discussed in the AAW below, this is a structural component), but Treasuries have rallied and gold has declined. This would suggest more worries about an economic downturn and less about inflation. Some of this reaction may be based on expectations that the Fed will maintain inflation expectations by lifting rates. Supporting that notion were comments late yesterday from Governor Brainard who suggested that growth “tailwinds” may speed policy tightening.[1] What makes this remarkable is that Brainard is one of the most dovish members of the FOMC, a consistent voter for accommodation. For her to turn even modestly hawkish does indicate tighter policy is likely.

How important is Cohn’s departure? From day one we framed the administration as made up of factions, populists and establishment. The former support policies that harm capital and support inflation, while the latter want policies that boost capital and contain inflation. The backdrop of the Trump presidency has been a consistent battle between these two sides. At first, the populists were winning, with Bannon and Miller seemingly driving policy. The ouster of Preibus and the installation of Kelly as Chief of Staff brought order and the rise of the establishment. The tax cuts were the clearest evidence of establishment power. Cohn’s departure suggests a populist counterinsurgency. But, it is clear that Trump doesn’t consistently favor one side over the other. Instead, he seems to foster an “ebb and flow” between the two sides. This is partly a function of his management style. He seems to like to watch conflict and use it to make decisions. So, now that it appears that the populists are winning, it wouldn’t be a shock to see him do something that flips the script. One signal of that would be replacing Cohn with Larry Kudlow, an avowed supply side economist who would also strongly oppose trade barriers. And, Cohn might not be completely gone. There have been rumors that he could replace Kelly as Chief of Staff.

So, there are two core ideas that we are using to analyze policy. First, pundits are turning themselves inside-out trying to divine the “real” Trump and watch him develop a consistent set of policies only to see constant vacillation. This isn’t a bug in Trump’s management, it’s a feature. No faction ever gets complete control because that would mean Trump loses the ability to change course. Trump does believe, at a visceral level, that trade deficits are “losses.” That is a common belief, but the reality is much more complicated. As a clear example, there is only one autarky in the world, which is North Korea. No other nation is trying to emulate the Hermit Kingdom’s economy. In other words, trade is good for an economy. In fact, if the president really wants to affect trade, he should have signed on to the border adjustment tax idea that was floated as part of the corporate tax reform. That would have raised import costs, likely reduced the trade deficit and made tax reform revenue neutral. But, that would have also taken away the president’s ability to bargain by offering and taking away benefits. In other words, the border adjustment tax would have affected trade in his favored direction efficiently at the cost of negotiating flexibility. The president seems to prize the latter over everything.

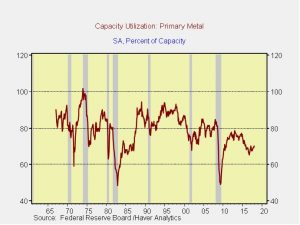

Second, although we watch the administration, we firmly believe in trends, not people. The rise of populism and a revolt against the establishment and capital is underway. Election results in Italy last weekend are just another example of this phenomenon. Trump’s election was part of this wave. However, he isn’t a perfect “vessel” of the trend because he does want the support of the establishment at times. So, we have tax cuts, which populists don’t necessarily favor. But, trade impediments are clearly part of the populist package. Although the Cohn news dominated, we also note Bloomberg is reporting that the U.S. is considering broader action against China for violating intellectual property rules.[2] That’s a much bigger deal. Thus, there is likely more protectionism to come. One of our paradigms is that economies go through 30- to 50-year cycles of efficiency versus equality. During the former, deregulation and globalization are supported, while it’s just the opposite during the latter. We have been in an efficiency cycle since 1978. We are moving into an equality cycle, although it may take another decade for it to become completely obvious. But, the tipping point is being reached. Trade impediments and reregulation are a likely outcome.

So, where does this leave us? The economy is still doing very well. Earnings are robust. The path of equities really comes down to the multiple. Based on consumer confidence, the multiple should be fine but what we saw yesterday can upend confidence and eventually lead to a falling P/E. For now, we still think the risk for equities is to the upside. If Cohn’s replacement is an establishment figure, equities will likely recover. We are much more worried about 2019; a tighter Fed and a lessening of the fiscal boost have the potential to weaken the economy and earnings. But, for now, we still think odds favor rising equity prices.

[1] https://www.bloomberg.com/amp/news/articles/2018-03-07/brainard-suggests-growth-tailwinds-may-speed-fed-rate-hike-pace?__twitter_impression=true

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/amp/news/articles/2018-03-06/u-s-said-to-consider-broad-curbs-on-chinese-imports-takeovers?__twitter_impression=true