Author: Rebekah Stovall

Asset Allocation Weekly (October 2, 2020)

by Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

The death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg was yet another political shock for 2020 in a year rife with unusual events. The year began with the first official case of COVID-19 in Washington State on January 20. The pandemic and subsequent measures to contain the virus have led to unprecedented levels of economic volatility. President Trump was acquitted of impeachment on February 5. Relations with China have deteriorated.

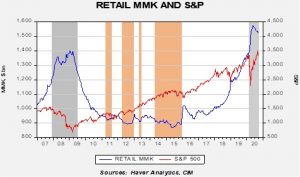

As we head into the election, investors’ fears are high. For example, retail money market funds (RMMK) remain elevated, though off their earlier peaks.

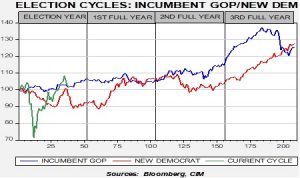

Our political cycle monitor suggests that a Biden win could result in a decline in equities into October.

Barring an unexpected landslide, it is quite possible that this election could be disputed. The last time this occurred, in 2000, the election wasn’t decided until December 12, when the Supreme Court effectively ended the recount. George Bush won a narrow victory in Florida and in the Electoral College (271/266). The financial markets were affected by the outcome; in the period from the election on November 7 until the Supreme Court decision, the S&P 500 range from high (made on November 8) to low (made on December 1) was 9.9%. A decline of this magnitude would probably not be enough to warrant substantial portfolio adjustments.

Voter attitudes were not nearly as hardened then as they are now. A Pew survey suggested that 45% of voters thought that the winner really mattered, while 49% believed “things would remain about the same.” Currently, 83% of voters think it really matters who wins and only 16% believe that “things would remain about the same.” The Pew survey suggests that this election is being viewed as zero-sum; losing is perceived as devastating, so both sides are primed to contest a close election.

Although equity markets have performed quite well from their March lows, the recent weakness does appear to be starting the process of discounting a Biden victory. Although we would not necessarily expect a decline to the 90% level implied on the above chart,[1] a period of weakness in the next few weeks is likely.

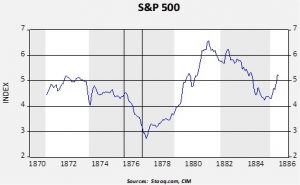

Is there a precedent for the current election? The best analog is the 1876 election, which was won by Rutherford B. Hayes in the electoral college by a single vote, 185-184 over Samuel J. Tilden. And, that result only occurred weeks after the November ballot. Hayes was given the presidency in return for ending Reconstruction. An analysis of this election will be the subject of an upcoming WGR, but the following chart offers some idea of the impact of an uncertain election outcome when it is perceived as zero-sum.

From March 1876 to March 1877 (when Hayes was inaugurated), the index, on a monthly average basis, fell 29.7%. Although the recovery from the lows was robust, the March 1876 level was not exceeded until October 1879. As we will discuss in the upcoming WGR, the 1876 election occurred during the long depression that began with the Panic of 1873, which was considered the worst economic downturn until the Great Depression. Thus, the disputed election cannot be blamed for the entire decline, but it likely contributed. Increased tensions in the November election is a factor the Asset Allocation Committee will grapple with in the upcoming portfolio rebalance.

[1] To quote Ned Davis, a famous market analyst, cycle analysis shown above should be used more for direction and less for level.

Weekly Energy Update (October 1, 2020)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

Here is an updated crude oil price chart. The recent dip in prices remains, although we are seeing some recovery.

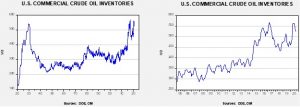

Crude oil inventories fell when a build was expected. Commercial stockpiles declined 2.0 mb compared to forecasts of a 2.0 mb rise. The SPR declined 8.8 mb; since peaking at 656.1 mb in July, the SPR has drawn 12.8 mb. Given levels in April, we expect that another 8.2 mb will be withdrawn as this oil was placed in the SPR for temporary storage. Taking the SPR into account, storage fell 3.8 mb.

In the details, U.S. crude oil production was unchanged at 10.7 mbpd. Exports rose 0.5 mbpd, while imports were steady. Refining activity rose 1.0%.

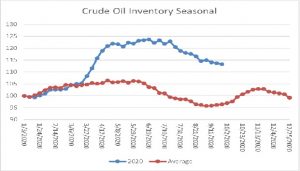

The above chart shows the annual seasonal pattern for crude oil inventories. This week’s data showed a decline in crude oil stockpiles, which is contra-seasonal. Inventories tend to make their second seasonal peak in the coming weeks. Tropical activity has started to wane (it usually ends by Halloween), so the continued decline is bullish for oil prices.

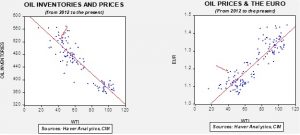

Based on our oil inventory/price model, fair value is $42.90; using the euro/price model, fair value is $63.11. The combined model, a broader analysis of the oil price, generates a fair value of $52.56. The wide divergence continues between the EUR and oil inventory models. As the trend in the dollar rolls over, it is bullish for crude oil. Any supportive news on reducing the inventory overhang could be very bullish for crude oil.

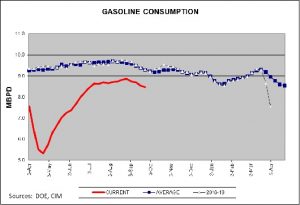

Gasoline consumption continued to decline this week. Seasonally, this is normal. Driving tends to slow as vacation season ends. As the chart shows, consumption declines slowly into mid-January. This year may be different; if a vaccine is developed that increases commuting then we could see driving levels rise, but without that result we should expect overall demand to fall through Q4.

Kuwait’s emir, Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah, died this week at 91 years old. He was the ruler of Kuwait when Saddam Hussein invaded in 1990. After that event, Kuwait became a close ally of the U.S. He will be succeeded by his half-brother, Crown Prince Sheikh Nawaf al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah; however, the incoming emir is advanced in age (83 years old) and in poor health. There is a potential leadership conflict that may develop once he dies or becomes incapacitated. The emir opposed normalizing relations with Israel, but with his passing there would be a higher likelihood of Kuwait joining the UAE and of Bahrain recognizing Israel.

Saudi Arabia claims it dismantled a terror cell that had ties to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Iran remains a threat to the Arab states in the region.

Last week, we discussed the growing fear that oil demand has peaked. Demand concerns have kept prices in a tight range, offsetting the bullish impact of dollar weakness. California’s new ban to prevent the sale of internal combustion engine cars by 2035 is further evidence that peak demand may be, at best, coming in the near future. Russian oil companies are criticizing the “green” direction of European oil companies, suggesting it is creating an “existential crisis” for oil supplies. Perhaps another way of thinking about this issue is that it is creating an existential crisis for Russian oil companies.

View PDF

The Case for Hard Assets: An Update (September 2020)

by Bill O’Grady & Mark Keller | PDF

Background and Summary

In this report, we use the term “commodities” to imply “hard assets.” In our definition, the latter is a commodity that requires multiple years to generate a supply response. This definition excludes agricultural commodities, which tend to create a supply response on an annual basis. That doesn’t mean all agricultural commodities have short-term supply responses. Coffee trees, for example, take three to four years to mature. But, once a tree is mature, a new crop occurs annually. Compare that to a mine which takes years from inception to producing ore. Even oil wells take about a year to drill (from pre-drilling work and actual drilling). Thus, a portfolio based on hard asset commodities will tend to have less supply volatility compared to soft asset commodities.

Secular markets are defined as long-term trends in an asset. There are both secular bear and bull markets. For example, a secular bull market in bonds is characterized by falling inflation expectations that trigger steady declines in interest rates. A secular bear market in bonds is caused by the opposite condition―rising inflation expectations which lead to consistently rising interest rates.

Commodity markets have secular cycles as well. Commodity demand is mostly a function of economic and population growth. Commodity supply comes from agriculture, ranching, mining, and drilling. In capitalist economies, technology usually acts to reduce demand and increase supply. Over time, we have seen consumption per unit fall for many commodities. Technology tends to reduce our per unit consumption; we get more output from consuming less commodities. Technology also enhances production. For example, agricultural technologies have improved production and reduced inputs. The impact of shale technology has revolutionized the oil and natural gas industry. Although globalization and trade can improve commodity demand, it also can make supplies more secure and lead to reduced inventories.

As a general rule, peace, stable economic growth, and orthodox monetary and fiscal policy tend to act as depressants on commodity prices. War, unusually strong economic growth, a breakdown in global order, and unorthodox policy are usually bullish for commodity prices.

Daily Comment (September 30, 2020)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] | PDF

Our Daily Comment today provides a short recap of last night’s presidential debate, as well as an update on the fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh. Next is a discussion of today’s positive economic data out of China. We also discuss some new developments in global monetary and regulatory policy, and finally, a few sundry other interesting tidbits.

U.S. Elections: President Trump and Joe Biden had their first debate of the presidential campaign last night, although you could be forgiven for thinking the debate was between Trump and moderator Chris Wallace, given their extended sparring. Our initial impression was that both Trump and Biden avoided any major campaign-killing gaffes, without scoring any knockout punches. Everyone from political analysts to individual citizens will now be assessing how things went, and a different consensus might arise over the coming day or two. For now, however, the most likely scenario is that the event will do relatively little to change the character of the race. All the same, the name-calling and insults did highlight the risk of political instability surrounding the election, which helps explain the modest pullback in stocks so far today.

Nagorno-Karabakh: For the fourth straight day fighting continues in Azerbaijan’s breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh, with Azeri forces and ethnic Armenian rebels launching attacks in several directions along the so-called Line of Contact dividing them. The fighting is now spreading well beyond the borders of the enclave and threatening to spill into all-out war between the former Soviet republics of Azerbaijan and Armenia. Even worse, the conflict has also threatened to draw in Russia, which has a security alliance with Armenia, and Turkey, which said today that it will back Azerbaijan with “every means available” in the conflict.

China: The country’s official Purchasing Managers’ Index for manufacturing rose to a seasonally adjusted 51.5 in September, beating both the expected level of 51.2 and the August reading of 51.0 (see data tables below). Like most major PMIs, the index is designed so that readings over 50 indicate expanding activity, so the gauge suggests the Chinese factory sector is continuing to recover from the coronavirus disruptions earlier this year. Since that means the Chinese economy could help power the global recovery, the news should be bullish for risk markets, although perhaps not enough to offset the growing concerns about resurgent infections and political tensions.

- A separate private gauge of activity, the September Caixin Manufacturing PMI, fell slightly but was still robust at 53.0.

- The official nonmanufacturing PMI, which includes both the service and construction sectors, jumped to 55.9 in September, its highest result since November 2013 and better than the previous month’s reading of 55.2.

Global Monetary Policy: For the first time, European Central Bank President Lagarde said the ECB would consider following the lead of the U.S. Federal Reserve by committing to let inflation overshoot its target after a period of sluggish price growth. However, she also sounded skeptical of the more flexible approach to monetary policy, adding, “Make-up strategies may be less successful when people are not perfectly rational in their decisions — which is probably a good approximation of the reality we face.” Of course, another concern with the new approach is that it could help fuel asset bubbles, as discussed recently by Dallas FRB President Kaplan.

Global Technology Industry Regulation: In an effort to improve competition and reduce the dominance of big, multinational technology firms (many of which are U.S. companies), a draft of the EU’s proposed Digital Services Act would require those companies to share data collected on their platforms with competitors if they want to do business in the EU. Meanwhile, the House Antitrust Committee is completing a probe that could result in legislation forcing the separation of online platforms. The developments highlight the growing regulatory risks faced by multinational tech firms, despite their strong outperformance in the stock market until recently.

European Union-United Kingdom: The U.K.’s chief Brexit negotiator, David Frost, conceded that the EU has refused to provide preferential import terms to British auto manufacturers in the trade deal he’s negotiating with Brussels. With four out of five British-made cars being exported, mostly to the EU, it raises prospects that the industry would face major disruptions even with a trade deal. The auto provision and other stumbling blocks continue to suggest a hard Brexit without a deal is becoming more and more likely.

Kuwait: The government announced that the country’s ruler, Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah, died yesterday at the age of 91. He has been succeeded by his half-brother, Crown Prince Sheikh Nawaf al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah, but he is 83 and in poor health. He isn’t expected to make dramatic changes to Kuwaiti policies. The real issue for Kuwait is the battle to succeed him as crown prince, which could prove divisive and drawn out. A key question is whether Kuwait will now continue its steadfast support for Palestinian statehood or follow the lead of the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain in finally recognizing Israel.

Cuba: The Cuban government is stepping up plans to devalue the peso for the first time since the 1959 revolution, as a dire shortage of tradable currency sparks the gravest crisis in the communist-ruled island since the fall of the Soviet Union.

COVID-19: Official data show confirmed cases have risen to 33,700,008 worldwide, with 1,008,874 deaths and 23,426,047 recoveries. In the United States, confirmed cases rose to 7,191,406, with 206,005 deaths and 2,813,305 recoveries. Here is the interactive chart from the Financial Times that allows you to compare cases and deaths among countries, scaled by population.

Virology

- Confirmed U.S. infections rose by more than 40,000 yesterday, roughly in line with the seven-day moving average of new infections. The seven-day moving average of deaths related to the pandemic remained at about 750. Infections continue to surge in some areas, including parts of New York City and in the Upper Midwest.

- The National Football League reported its first team breakout of the disease, with three players and five staff members in the Tennessee Titans organization testing positive. That prompted the Titans and the Minnesota Vikings, who played them on Sunday, to suspend all in-person club activities.

- With infections rebounding strongly in Russia, and in Moscow in particular, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin said the city would extend regular school holidays in October to two weeks to help contain the spread of the virus. Last week, the mayor urged anyone aged 65 years old and older to stay home.

- Canada is seeing a sharp rise in cases of COVID-19, alarming health officials and triggering a second round of lockdowns and strict distancing recommendations.

- Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen Hahn insisted yesterday that his officials would assess any coronavirus vaccine application against a previously published set of criteria that would make it all but impossible for a shot to be available in the U.S. before November’s election. The statement sets up possible new friction with President Trump, who has threatened to overrule those guidelines.

- Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (REGN, 573.61) said preliminary results from a clinical trial showed its experimental COVID-19 drug helped reduce virus levels and improved symptoms in sick patients who weren’t hospitalized, advancing development of a medication that could be among the first to treat the illness in its early stages.

Economic Impacts

- The Walt Disney Company (DIS, 125.40) said it would lay off about 28,000 employees at its U.S. theme parks who had been on furlough since April. In a statement, the firm said a key reason for the decision was the California state government’s pandemic restrictions, which would keep its Disneyland resort closed for the foreseeable future.

U.S. Policy Response

- House Speaker Pelosi and Treasury Secretary Mnuchin had a lengthy telephone call yesterday about the Democrats’ latest proposal for additional pandemic relief, and they are scheduled to continue their discussions today. The Democrats’ bill, which would total about $2.2 trillion, described in detail in our Comment yesterday, could be voted on as early as today or tomorrow. Pelosi expressed confidence that the two sides could come to an agreement, but the bill would still face tough sledding in the Senate.

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Erdoğan’s Leadership and the Turkey-Greece Dispute: Part I (September 28, 2020)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

When talking about international relations, it’s tempting to describe each country as a monolithic, rational decisionmaker with a settled set of concerns, goals, strategies, and tactics. Examples of such descriptions include: China wants to solidify its claim to the South China Sea; Russia is trying to undermine Western democracies; and the U.S. has tired of global hegemony. This convenient shorthand makes it easier to talk about geopolitics, but it can mask the reality that a country’s behavior is driven by the decisions and initiatives of powerful individuals. Those decisions and initiatives may reflect the country’s traditional perspectives, lessons from history, and habits developed over centuries. They may incorporate today’s popular opinion or the preferences of the ruling classes. But a country’s policies still reflect the decisions of individuals in power as constrained by their personal, political, and bureaucratic environment. Without Napoleon, it’s unlikely that post-revolutionary France would have embarked on its aggression against the rest of Europe in the way that it did. Without Adolf Hitler, neither would post-World War I Germany have done so.

If leaders and leadership really do count, a good example today is Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the way he’s deploying Turkey’s power in Asia Minor. In Part I of this report, we provide a deep dive into Erdoğan’s perspectives, goals, power, initiatives, and constraints. Next week, in Part II, we’ll show how Erdoğan is trying to make Turkey a player in the newly discovered, rich natural gas fields of the Eastern Mediterranean. Since that initiative could lead to a confrontation with other countries, Part II will also explore the potential implications for investors.

Daily Comment (September 25, 2020)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] | PDF

It’s Friday and we are closing another week. Equity markets continue to struggle. We lead off with policy news from around the world (including the U.S.). China news is next. We update the pandemic news followed by international news. As promised, a bonus chart is presented. And, being Friday, a new Asset Allocation Weekly report, podcast, and chart book are available. Here are the details:

Policy news: There are a number of developments worldwide as the Northern Hemisphere prepares for winter under pandemic conditions.

- House Democrats are putting together a new aid proposal. The fact that this is going out is not good news. Some Democratic representatives in “purple” districts want to approve some form of help, even the “skinny” bill offered by the GOP. The Speaker does not want to accept the GOP offer for two reasons. First, she thinks it’s inadequate, and second, she thinks she has leverage and can get more of what her party wants. To placate the uncomfortable representatives, she is offering a compromise bill that has spending levels well above that which the GOP has suggested it will accept. If she thought she had a chance of a deal, she wouldn’t bring this bill to the floor. She is likely bringing this bill to provide political cover for the purple district reps. We do not expect additional aid to be available until after the election. Although the economy is in recovery, there is evidence in the high-frequency data that the pace of growth is slowing. Given the reporting lag, if a slowdown is coming, it won’t be until well into Q4.

- U. K. lawmakers are shifting to a wage subsidy program, similar to Germany’s, and ending direct wage replacement. The new program shifts the burden of incidence to employers. The risk of the new program is that employers won’t keep workers on payrolls, but the government likes the lower cost. One interesting theme of the U.K. policy response is that it looks like the Johnson government is starting to prepare the country for a post-pandemic economy that will be fundamentally changed. There has been an underlying assumption in the West that the pandemic will fade, and everything will return to the pre-pandemic conditions. That assumption is slowly being replaced with the idea that even with a vaccine, the future world will not be the same.

- The IRS is moving to improve tax reporting on cryptocurrencies. This action may force Congress and regulators to actually define what these “things” are. Although proponents want them classified as currencies, they look to us more like securities, and capital gains on securities are taxable. Interestingly enough, capital gains on cash are not. If we have deflation, the gains from cash are not taxed.

- Europe is becoming more aggressive with member states that give companies special tax treatment. Such actions will exacerbate the constant tension between the EU and the sovereign nations within the union.

- With the Turkish lira in a near freefall, the central bank finally moved to raise interest rates. President Erdogan tends to oppose such measures, so we will be watching to see if any members of the central bank “resign” in the near future.

China news:

- FTSE/Russell has added Chinese sovereign debt to its bond indices, a move that will require passive managers to add some $100 billion of Chinese bonds to their portfolios. This action is further evidence of China’s growing inclusion into the global financial system.

- The Evergrande Group (EGRNF, $2.05), China’s second-largest property developer, is reportedly facing a cash shortage. The company is heavily indebted and is working on restructuring. A reported leak of a letter suggests the company is lobbying the government for help in its restructuring. The firm is probably too big to fail, and thus will get government aid; however, the leadership of the company may not be spared.

- The TikTok saga continues. It appears Trump administration officials are divided on the current arrangement. Meanwhile, the courts have delayed the implementation of a ban on the app, and the court seems inclined to give the company an injunction against the government’s plans to force the app off American phones.

- The SoS is warning states that China is attempting to woo them and divide the U.S. response against China.

- Germany will not impose a full ban on Huawei (002502, CNY 2.71), further evidence that the Merkel administration is not willing to fully commit to the U.S. policy on China.

- Further evidence that the Xi government is deepening its hold on private business in China is that the government has released a strategic emerging industries plan to further its goals of technological independence.

COVID-19: The number of reported cases is 32,273,914 with 983,720 deaths and 22,261,136 recoveries. In the U.S., there are 6,979,973 confirmed cases with 202,827 deaths and 2,710,183 recoveries. For illustration purposes, the FT has created an interactive chart that allows one to compare cases across nations using similar scaling metrics. The FT has also issued an economic tracker that looks across countries with high frequency data on various factors. The R0 data show 19 states with falling cases, and 31 with a rising trend. Ohio has the lowest infection rate, while Washington has the highest.

Virology:

- Novavax (NVAX, 102.44) has begun the final testing phase of its vaccine, the 11th candidate in the final stage. In the early testing, the company’s vaccine appeared to generate a robust immune response, raising hope that it may be particularly strong.

- As cases rise in Europe and surrounding areas, Israel has expanded its lockdown to bring a flare-up under control.

- COVID-19 has ravaged Tunisia’s economy. In response, an increasing number of Tunisians are trying to emigrate to Europe. As the emerging world suffers from the virus, a secondary effect may be a wave of emigration to the West.

- The Pac-12 will resume football.

International news:

- The U.S. no longer officially recognizes Belarus President Lukashenko as the legitimate head of state. This news comes after Lukashenko was sworn in as president in a secret ceremony.

- Alexei Navalny has been discharged from the hospital. He is expected to return to Russia. When he gets there, he will have trouble getting money; the government has frozen his financial accounts.

- The EU wants to create a new policy for dealing with refugees. The plan is to distribute them across the union rather than housing them in the nation where the refugee disembarks. This is unpopular with the central European nations; in return, the EU is offering cash to encourage them to accept more foreigners.

- Earlier this week, a South Korean official, apparently attempting to defect to North Korea, was captured by border control agents who killed the man and burned his remains. In a rare apology, Kim Jong Un said he was “very sorry” about the incident.

- Mexico is no stranger to political corruption. Transparency International puts Mexico in the same league as Myanmar and Laos. It ranks 130 out of 191 countries. Ukraine is marginally less corrupt. Mexican presidents serve a single six-year term, and their successors usually don’t prosecute them for their corrupt actions during office. When the PRI dominated Mexico, the outgoing president selected his successor, ensuring the outgoing leader would be left to a quiet retirement. AMLO is ending this tradition, accusing five former presidents of corruption with the goal of bringing them to justice. It isn’t clear whether any of them will actually face prison time, but the move is politically popular.

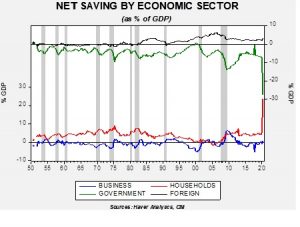

Bonus Chart: In macroeconomic accounting, all saving has to net to zero. That’s because the process is a sort of balance sheet. The reason we look at net saving is to determine where the flows are moving. We have just received the data for Q2, and they are remarkable.

Due to the CARES Act, we saw massive dissaving from the government sector; another way of saying this is the deficit widened. Note that the bulk of the saving is being held by households, although the rise in the current account, which includes foreign saving, also rose. This data indicates that households are holding large saving balances that will eventually flow back into the economy as spending.

Asset Allocation Weekly – #12 (Posted 9/25/20)

Asset Allocation Weekly (September 25, 2020)

by Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

For more than a decade, U.S. investors who diversified their risk assets to include foreign equities have been sorely disappointed in the results. Since September 2010, for example, the S&P 500 Index of large cap U.S. stocks has provided an average annual total return of approximately 13.9%, but the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. Index of foreign stocks has provided a total return averaging just 4.6%. At those rates of return, an all-U.S. stock portfolio would have doubled in value every 5.2 years or so, whereas an all-foreign stock portfolio would have taken about 15.7 years to double. Even a broad index of U.S. corporate bonds would have beaten the broad foreign stock market over the last decade, with only about one-third as much volatility! It should be no wonder that many investors have chosen to exclude foreign stocks from their portfolios.

But if you understand the key drivers behind the U.S. outperformance and foreign underperformance in recent years, it can clarify your thinking about the proper asset allocation strategy for the coming years. As we’ve argued repeatedly, much of the difference in U.S. versus foreign stock returns can be traced to the foreign exchange value of the U.S. dollar. When the greenback is strong and appreciating, the broad U.S. stock indexes tend to show better returns than the foreign indexes. Indeed, the dollar was generally rising from mid-2011 to mid-2020, explaining much of the U.S. outperformance over the last decade. In contrast, when the greenback is weak and falling, foreign indexes tend to outperform. That’s important because it appears the dollar has recently rolled over and begun what could well be an extended slide. If so, the coming period is likely to strongly favor foreign stocks.

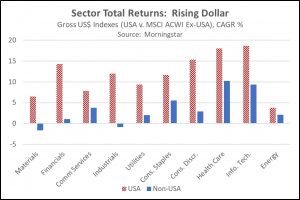

Of course, some of the recent outperformance of U.S. stocks simply reflects the preponderance of large cap Technology and Health Care names in the U.S. indexes. Those stocks have been particularly in vogue and have shown extraordinary growth in recent years. Nevertheless, taking a deeper dive into the relative performance of U.S. and foreign stock market sectors shows that the strength of the dollar is the predominant factor. If foreign stocks outperform U.S. stocks across a wide variety of sectors during a weak-dollar period, it should help confirm that the relationship is the most useful guidepost, and that is indeed what the data shows. This can be seen by examining the first chart below, which shows the outperformance of U.S. stocks (represented by striped red columns) versus foreign stocks (solid blue columns) over the last two strong-dollar periods from May 1995 to February 2002 and from May 2011 to July 2020. During these periods, U.S. total returns roundly beat foreign stock returns in all sectors for which comparable data was available (the data exclude real estate).

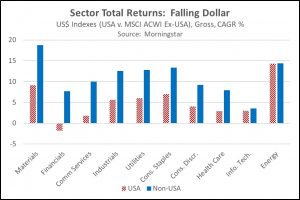

In contrast, the chart below shows how dramatically foreign stocks turned the tables during the period of dollar weakness from February 2002 to May 2011. In this period, foreign stocks handily beat U.S. returns in almost all sectors. The sectors are shown, from left to right, in the order by which the foreign returns beat the U.S. returns. The graph clearly demonstrates how dramatically foreign Materials, Financials, Communication Services, and Industrials stocks outperformed their U.S. counterparts as the dollar declined. Given the significantly greater exposure to Materials, Financials, and Industrials in the foreign indexes, those sectors account for most of the overall foreign outperformance during the weak-dollar period. In the high-growth Information Technology and Health Care sectors, foreign stocks also outperformed their U.S. counterparts as the dollar declined, but the relative underrepresentation of those stocks abroad kept the foreign outperformance smaller than it otherwise would have been.

Although the data set used in this study only began in 1995, covering just two rising-dollar periods and one falling-dollar period, the relationships described above make logical sense. For example, a low or falling dollar tends to support commodity prices, so foreign Materials firms should see improved finances when the greenback is sliding. Our analysis also indicates that foreign emerging market stocks have an even more pronounced advantage in a falling-dollar phase. In sum, the analysis indicates that if the dollar is indeed falling into a prolonged downtrend like we think, the new investment environment is likely to favor a wide swath of foreign equities in the coming years.