by Bill O’Grady and Kaisa Stucke

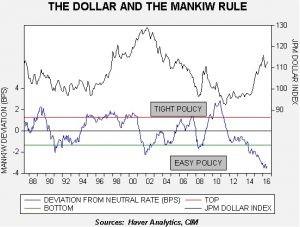

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] Market movement this morning is eerily quiet. The change in currencies is small, energy is roughly unchanged as are Treasuries. The lack of activity in front of Yellen’s remarks (which formally begin at 10:00 EDT) suggests that (a) the markets are mostly “squared” in front of the speech, meaning traders are not leaning in either direction, or (b) they have decided on a stance (dovish) and are vulnerable to a hawkish surprise. We lean toward the latter. On the other hand, we doubt her talk will be hawkish. In fact, we doubt it will say much at all about the current situation. We expect her speech to mostly focus on operating monetary policy in a low nominal interest rate environment. In other words, when the economy does slip into recession, the FOMC probably won’t be able to cut rates significantly. If this is the case, how will policymakers stimulate growth? We expect the Yellen paper to offer ZIRP, forward guidance and QE. NIRP will be mentioned but likely only as a last resort.

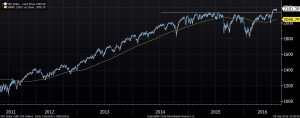

If our projection is correct, how will the markets react? Since we have seen rate hike expectations creeping higher on the back of recent FOMC member comments, Yellen’s comments will be seen as neutral to dovish. That outcome will be modestly bearish for the dollar, bullish for gold and commodities and supportive for equities and Treasuries.

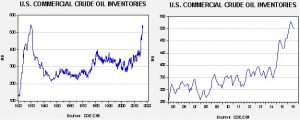

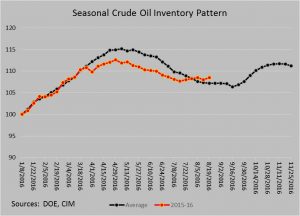

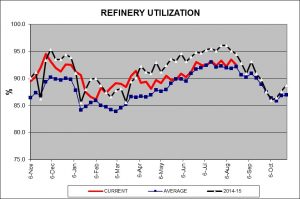

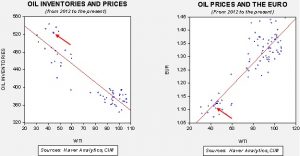

In other news, the Saudi energy minister, Khalid al-Falih, indicated today that the talk of a production freeze isn’t a big deal and added that the market is moving toward balance without outside intervention. This would seem to be a bid to temper expectations for next month’s meeting. Iran told Reuters that it would be willing to help stabilize oil prices as long as OPEC members allow Iran to gain market share…which is, of course, silly. Saudi oil policy, by design, is to gain and keep market share. The only way Iran can gain market share while allowing Saudi Arabia to achieve its production goals is if the other OPEC members cut output. That might occur but it won’t be due to policy—it would be due, most likely, to geopolitical events, e.g., a civil implosion in Venezuela. Since that isn’t much of a policy, we suspect the OPEC meeting won’t be able to maintain prices on its own. In fact, we note that the Saudis are planning to sell a dollar based bond soon. It might be that the kingdom is trying to prop up oil prices in front of that bond sale, which will bear watching.

We are also continuing to monitor rising naval threats to shipping in the Persian Gulf. Iranian vessels, operated by the Iranian Republican Guard Corp (as opposed to the tiny, official Iranian navy), have been playing “chicken” with U.S. warships. Over the past few days, the U.S. has fired warning shots at these vessels that were making threatening passes at U.S. ships. Iran appears to be increasing tensions in this area—the question is why? Gillian Tett of the FT has an op-ed today where she notes how the lack of clarity surrounding the DOJ’s treatment of foreign banks operating in Iran has led most foreign banks to shun Iranian business. Although the Obama administration has formally lifted the ban, there are other U.S. laws, such as counter-terrorism regulations, that might potentially snare foreign banks. Thus, the lifting of sanctions after the nuclear deal has not led to massive investment in Iran. It is not out of the question that Iran is expressing its frustration with U.S. policy through these naval acts. We should note that U.S. banks continue to be prohibited from doing business in Iran.

Finally, the Brazilian Senate has begun its impeachment trial against President Dilma Rousseff. To impeach the president, two-thirds of the 81 senators must vote to remove her from office. If the vote passes, as expected, VP Temer will be elevated to president and hold office until Rousseff’s term ends in 2018. Brazilian financial markets have rallied on expectations that Temer will be more business friendly than the leftist Rousseff, but we note that Temer is beset by low approval ratings and personal corruption. If the impeachment vote fails, we would anticipate market disappointment. However, even if it passes, as expected, the left will likely become obstructionist and Temer’s own shortcomings could weaken Brazilian financial markets.