by Asset Allocation Committee

Last week, we reviewed Sebastian Mallaby’s recent biography of Alan Greenspan.[1] This week, we will focus on the issue of financial crises and financial stability. As noted in last week’s review, the financial system has evolved from a disjointed and diffuse system where banks could not establish themselves across state lines to one of increasing interconnectedness and concentration. Although this has made the financial system more efficient, it has also made it less robust. Simply put, we have created a “too big to fail” problem that means that the Federal Reserve must stand ready to intervene and support failed financial firms to prevent a broader systemic meltdown. This factor, coupled with inflation targeting, means that policy will tend to produce rising financial asset markets that are prone to infrequent large bear markets. The analogy we have used in the past is similar to a forestry policy that will not tolerate any forest fires. By preventing small fires, excessive underbrush grows, creating conditions that allow for extreme fire events that are difficult to control. By constantly rescuing smaller financial firms, policymakers encourage excessive risk which leads to unstable financial markets.

If FOMC officials are convinced that regulators and financial policymakers will not address the “too big to fail” issue effectively (and we tend to believe they won’t[2]), then in reality the Federal Reserve has three mandates—full employment, controlled inflation and financial stability. Currently, the FOMC uses monetary policy to address the first two mandates and relies on regulation to manage financial stability. The track record for regulation is poor—even Vice Chair Fischer noted that so called “macro-prudential regulations” don’t work all that well, based off his experience as head of the Bank of Israel.[3] Regulatory capture, the phenomenon where regulators are co-opted by those they regulate, is well-documented. The only effective policy available to manage financial stability is monetary policy—raising or lowering interest rates. However, it is very difficult for a central banker to raise interest rates because the equity P/E is too high or bond yields are too low; in fact, as we noted last week, it’s a good way for a central bank to see its independence stripped.

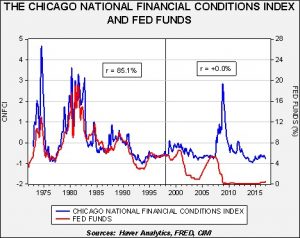

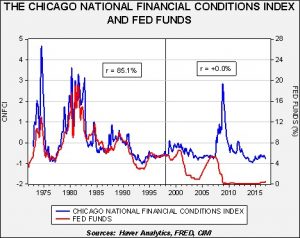

We have previously discussed the disconnect that has developed between financial stress and monetary policy.

This chart shows the Chicago FRB’s Financial Conditions Index (“CFRBFCI”) and the rate of fed funds. The CFRBFCI is a measure of financial stress—it has 105 variables that include interest rates, borrowing levels, outstanding debt, credit spreads, credit surveys and money supply among many other factors. In general, a rising number suggests worsening financial conditions and a reading above zero indicates worse than average financial conditions. From 1973, when the index was first created, until the end of 1997, the CFRBFCI and the level of fed funds were closely correlated, at +85.1%. When the Fed raised rates, financial conditions generally worsened and vice versa. Essentially, this relationship acted as a “force multiplier” for monetary policy. When the Fed raised rates, worsening financial conditions acted to depress the economy; when the Fed cut rates, improving financial conditions boosted growth. However, since 1998, the two have become completely uncorrelated. When the FOMC raised rates from 2004 to 2006, financial stress didn’t rise; when the financial crisis hit in 2008, the sharp drop in rates was slow to lower stress. In fact, it wasn’t until April 2013 before financial stress fell to pre-crisis levels.

We have puzzled over this change for some time. Mallaby’s biography of Greenspan offers one possible explanation. In 1998, during the Long-Term Capital Management meltdown and Asian Economic Crisis, the FOMC, pressed by Greenspan, cut rates 25 bps at three consecutive meetings (Sept. through Nov.). These cuts occurred in an environment of steadily falling unemployment. Simply put, the FOMC cut rates as financial stress rose even though the case for lowering rates was difficult to justify given the state of the economy. It appeared that investors concluded a policy asymmetry was in place—policymakers would cut rates if financial stress rose but would refrain from raising rates if stress was low. In other words, the “Greenspan put” on financial markets was in place.

This leads to a rather uncomfortable problem. If monetary policymakers are concerned that the financial system is fragile and cannot cope with much financial stress and they also conclude that regulators will never address this fragility due to regulatory capture, then they will be reluctant to raise rates and will only do so by clearly telegraphing their plans to avoid creating financial stress. There are four conclusions to draw from this problem. First, since the Fed will continue to target inflation, which is mostly held in check by globalization and deregulation (characterized mostly as the unfettered introduction of technological change), there will be a tendency for asset prices to reach unsustainable levels. Second, given the impotence of financial regulation, the FOMC will unofficially target the suppression of financial stress, also fostering higher financial asset prices. Third, investors will realize that the policy of suppressing financial stress will allow them to take on more risk.[4] Fourth, monetary policy will be only modestly effective in reducing financial stress when the inevitable drop in asset values eventually occurs.

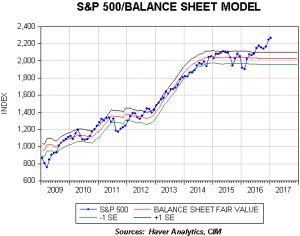

For investors, this policy situation creates a condition where one should remain invested in riskier assets until extremes in valuation are achieved.[5] History does suggest financial problems tend to occur during recessions, which is another factor we closely monitor. Overall, though, the central bank appears to be conducting policy in such a manner that supports asset prices and this is expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

View the PDF

______________________________

[1] Mallaby, S. (2016). The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

[2] There is an effective measure to address financial stability. It requires banks to hold more capital. That position is profoundly unpopular with banks because capital is something of a “dead weight” to the balance sheet. For a good introduction to this issue, we recommend the following podcast: http://www.npr.org/sections/money/2016/12/27/507125309/episode-744-the-last-bank-bailout

[3] https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/fischer20140710a.htm

[4] The problem discussed by Hyman Minsky. Minsky, H. (2008). Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill (First edition published 1986, Yale University Press).

[5] See Asset Allocation Weekly, 12/16/2016, for thoughts on equity levels.