by Bill O’Grady and Kaisa Stucke

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] It’s shaping up to be a very busy weekend. In Brazil, the Chamber of Deputies will vote over the next couple of days to decide if the legislature should begin impeachment proceedings. As we noted earlier this week, Brazilian financial markets have rallied on expectations that President Rousseff will be ousted at some point and the political turmoil will diminish. We doubt that will be the case. Although we suspect the legislature will vote for impeachment, Rousseff and her predecessor, Lula, still have widespread support and we would not be surprised to see a surge in civil unrest regardless of the outcome. Therefore, we suspect the financial markets have gotten a bit ahead of themselves and a post-impeachment vote correction is likely.

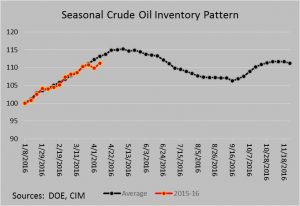

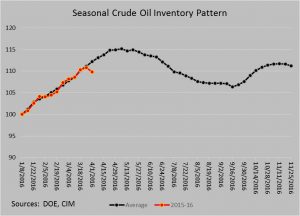

The other major event is the Doha oil producers meeting, bringing together OPEC members and Russia to decide on an output freeze. Oil markets have recovered strongly in anticipation that the freeze will be the first step in an agreement to reduce production. However, those hopes were dealt a blow this morning when Iran announced it would not send its oil minister but a second level representative instead; the news has oil prices falling this morning. Iran has made it abundantly clear that it is not planning to freeze output until its production reaches pre-sanctions levels. Saudi Arabia has sent mixed signals with regards to its plans; initially, there were reports that the Saudis would not promise to freeze without Iran doing the same. However, later comments suggested that the Saudis would probably go along with a freeze even without Iran. By downgrading its representation, Iran is signaling that there is no chance of a surprise freeze agreement. There was almost no chance even if its oil minister did attend, but a lower level functionary likely guarantees no change in Iran’s position.

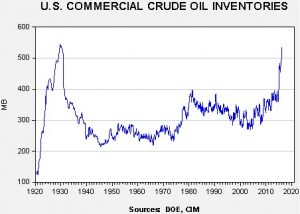

In general, we view a freeze as having a modestly positive impact at best. Most oil producers have been boosting output in front of the freeze meeting to ensure that they won’t have to reduce output as part of any agreement. It is positive for oil prices that major producers are in discussions. However, we don’t expect a freeze to have a material impact on the current supply situation. We agree with the IEA, who noted yesterday that the oil markets will achieve supply/demand balance by the end of this year, mostly due to declines in non-OPEC output, which will be sizeable in North America. Nevertheless, balance doesn’t address the inventory overhang which will take some time to reduce. We would not be surprised to see oil prices fall after this meeting, if for no other reason than the oil markets appear to have already discounted the most likely outcome, which is a promise to freeze output and a meeting environment that suggests cooperation, at least on the surface. Anything less than that could be much more bearish for oil prices.

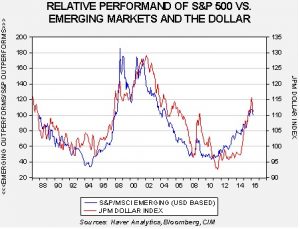

China’s GDP came in at 6.7% in Q1, within the new 6.5% to 7.0% range. As usual with China, it was a “good news/bad news” situation. The good news is that growth remains elevated. The bad news is that growth is coming the old fashioned way, from debt and investment. In Q1, total credit rose to CNY 7.5 trillion, a 58% increase over last year’s level and 46.5% of nominal Q1 GDP. For March, new loans rose CNY 1.37 trillion, well above expectations. New net corporate bond issuance rose CNY 695 bn. Yearly cement production rose nearly 25% for the first two months of the year. Total fixed investment, on a rolling quarterly basis, increased 10% but state sector investment rose 23%. Floor space jumped 40% from last year. Essentially, as China’s growth has slowed, it has returned to its old practices of boosting investment in the State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and housing, using massive amounts of debt to bring economic recovery. This has boosted commodity demand and emerging markets. There are two key unknowns. First, how long will this “goosing” last, and second, when does China run out of debt capacity? The goosing probably lasts into Q4 at the least but we would expect a return to rebalancing. The second question is a clear unknown. At some point, just as Japan discovered in the late 1980s, China will run out of borrowing capacity. Because it delayed restructuring, it will likely face years of sluggish growth. However, for now, China’s policy actions will be bullish for commodities and emerging markets.