by Bill O’Grady and Kaisa Stucke

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] It was a very busy weekend for news. Let’s take a look:

Terrorist attacks: There were a couple of bomb explosions over the weekend along with a number of unexploded devices found in the Greater New York area. The story is evolving but security officials have named two suspects and are seeking three others for questioning. Although police and FBI have stepped up their investigation, so far, the public and markets are taking this event in stride. There is no evidence of problems in the financial markets. Separately, a terrorist attacked and wounded nine people in a stabbing incident in a Minneapolis shopping mall. This assailant was killed by an off-duty police officer. IS did claim responsibility for the Minneapolis attack but has not made mention of the New York bombings. We will have a WGR on terrorism out later today.

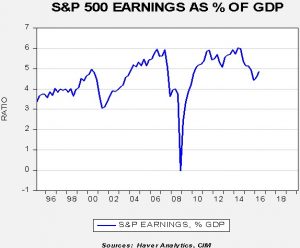

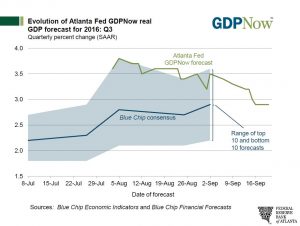

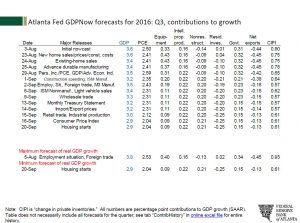

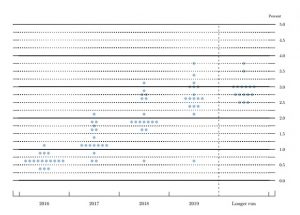

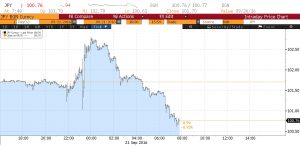

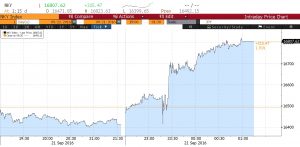

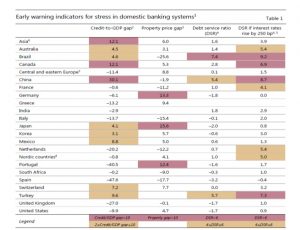

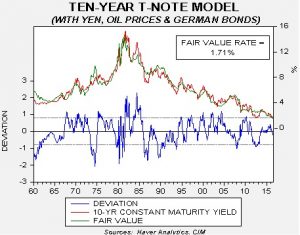

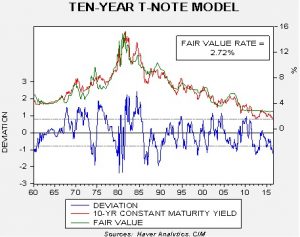

Central banks: The BOJ and Fed meet this week. Perhaps the most important is the BOJ meeting as this bank is starting to grapple with the problem of the exhaustion of monetary policy. Rumors continue to fly about what the BOJ will do. In our opinion, the key is getting the JPY to weaken. The most effective policy, QE with foreign bonds, probably won’t be implemented; we expect more QE. This may not satisfy the financial markets but it is also likely that this outcome has been mostly discounted. Meanwhile, the FOMC probably will not move this week but will likely signal a change by December. The WSJ has a profile of Boston FRB President Rosengren who has moved into the hawkish camp due to worries about overvalued financial assets. Although there is a case to be made for raising rates for this reason, it is hard for any Fed chair to go to Congress and explain that they raised rates because the stock market was too strong.

European elections: There were two elections over the weekend. In what was no surprise, the United Russia Party, which is Putin’s affiliation, won Duma elections in a landslide. The government had scripted the election, putting a virtual freeze on opposition media and thus making it nearly impossible for any opposition to campaign. United Russia won 76% of the Duma, or 343 seats, up from 238 in the 2011 elections. However, turnout was only 48% compared to 60% in 2011, suggesting that Russians are expressing their opposition by simply not voting. In Germany, the CDU, Chancellor Merkel’s party, lost ground in Berlin local elections, its second straight defeat in a local election. The populist AfD won 11.5% of the vote, which will give it proportional representation in the local government. The CDU won 18% of the vote, down from 23% in the last election.

OPEC meeting: OPEC meets informally next week and, according to the cartel’s secretary general, if a consensus is reached at this meeting then an emergency formal meeting could be held. According to Venezuelan officials, the group is “close” to an agreement. We do not expect any move to cut production; at best, OPEC may freeze output at current levels. However, Iran won’t agree to such a move and Saudi output is near record highs. Thus, a freeze won’t do much to relieve the overhang. Simply put, we look for more supportive talk but little supportive action.

An EU military: Saturday’s NYT reported that EU leaders are considering a consolidated military force, something that would have been impossible before Brexit. The U.K. would not allow its soldiers to come under EU control but, now that the British are leaving, European leaders are considering a joint military force with its command in Brussels. According to the article, the French are solidly behind the idea. France has always tried to use the EU to leverage its influence. Eastern European leaders were less enthusiastic about the plan for a couple of reasons. First, they fear that the force won’t be strong enough to deter Russia but an EU army might tempt the U.S. to pull back from NATO. Second, the French have never been keen on adding additional members in Eastern Europe and they worry a French-led EU military might be willing to offer them up to Russia in return for other favors. Under a President Trump, the EU may have no other choice than to remilitarize, so preparing for that possibility is probably prudent. However, given the EU’s inability to act in concert on most matters, it does seem like a long shot that they could coalesce around a plan to defend themselves. In addition, the EU has long acted as a “free rider” to U.S. military power and it would be a shock for EU governments to actually take up their own defense.

The deplorable state of the U.K. military: The front page, below-the-fold article in the weekend FT was a telling of the woefully inadequate state of the British military. According to the report, the U.K. has no plan to defend itself from a conventional attack, meaning a Russian attack might succeed. It appears the defense plan is to call Washington. The article also noted that Navy and RAF planes deploy without adequate munitions due to their growing dependence on the U.S. Additionally, manpower has become depleted as it lacks adequate depth and the government has spent too much money on a few items of expensive military equipment.

The devolution of the British Labour Party: Next weekend, the British Labour Party will hold its annual conference and is expected to re-elect Jeremy Corbyn as leader. Corbyn is an unrepentant leftist who is taking the Labour Party back to its platforms of four decades ago. Although the political class abhors Corbyn, the rank and file Labour Party members seem to like him a lot. If the process continues as expected, the Tories would be fools not to call a snap election. The Conservatives may not have a definable opposition if they do. On the other hand, the fact that Corbyn can hold his current position after years in the political wilderness speaks volumes about changes in the Western electorate.

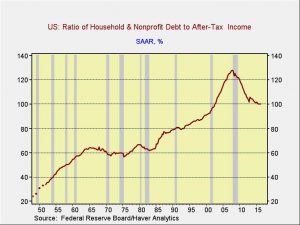

Good lives without good jobs: One of the more intriguing editorials in the Sunday NYT was about how to create good lives without good jobs. It discussed an ever growing safety net designed to boost household income for those earning low wages. This trend has been in place and growing for a while; we believe we are still in the early stages of this development. Globalization, deregulation and the rapid introduction of technology are creating conditions that offer an ever narrowing road to the middle class. For the bottom 50% of income brackets (and maybe up to the bottom 80%), jobs don’t pay well and have become increasingly uncertain. At the same time, without enough income for the majority of households, spending will be restrained as will economic growth. Social unrest will certainly rise. This isn’t a new problem; we have been tracking this trend since the late 1970s. However, the growth of household debt covered up this development and allowed this trend to continue. The financial crisis ended this response to weakening income growth. The article discusses how a patchwork of government programs, including disability, earned income tax credit, unemployment insurance, subsidies for health care, etc., have given households some support. Essentially, society has two choices. The first is a broader safety net that will provide some semblance of income for a workforce that is dealing with employment that is increasingly temporary and marginal, or a return to the 1950-60s model of essentially make-work programs where jobs were protected by regulation. The former model will mean higher taxes, low inflation and the continued expansion of technological and global progress. The second will lead to higher inflation, slower introduction of new technology, more regulation and less trade, but more people working. We suspect we will end up with something that takes a bit from both, but the preponderance will be from the first model.

View the complete PDF