- Although presidential elections gather a lot of attention from investors, we believe the specific person or party getting elected in this cycle may be less important than the forces driving the elections.

- The Fed is likely to raise rates gradually and we don’t expect the tighter policy to create a recession.

- Our equity allocations remain primarily domestic, although we believe emerging markets present an attractive return/risk opportunity for risk-tolerant investors.

- We include a range of maturities in our fixed income allocations.

- Our commodities allocation remains focused on gold to help address certain geopolitical and currency risks.

- Our style guidance remains modestly in favor of growth over value at 60/40.

ECONOMIC VIEWPOINTS

For over 16 years, including many prior to forming Confluence, we’ve worked together providing quarterly reports about our asset allocation models. And every four years we face a presidential election that often attracts an outsized amount of attention from investors. We frame it as outsized because the outcome of most presidential elections alone is generally not of great consequence to the markets. Elections certainly do have broad consequences, but the financial markets usually adjust pretty quickly.

This isn’t to say presidential elections are insignificant. But right now, the specifics of who occupies the White House is perhaps less important than understanding the changing force voters are exerting on the U.S. political system. So, regardless of which party takes the helm, both are going to have to deal with this force, which we expect to continue and grow well beyond this election cycle. What does this force look like? It’s complex and multifaceted, but we think it’s essentially a transition. We believe our economic philosophy is shifting away from an emphasis on efficiency, and more toward one of equality. We expect this shift to take years, and last for perhaps decades. If we are near the beginning of the transition, as we believe we are, there a few things for an investor to monitor.

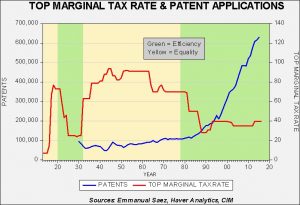

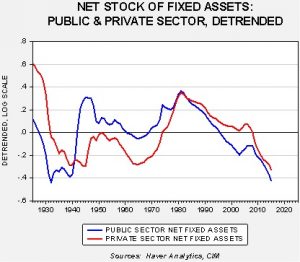

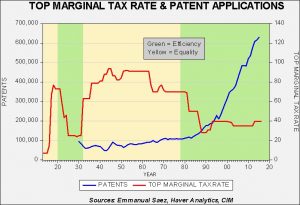

To begin, let’s consider what we mean by “efficiency” in the economy. With efficiency, tax rates and regulation are lower, fostering greater competition and innovation. Patent applications rise, along with technological developments that drive new products and processes. Business efficiency and profitability rise, while those building better mousetraps earn and keep significant wealth. Global trade rises as businesses seek to shift production to areas of lower cost, while simultaneously growing into new markets. Technology and globalization create obsolescence in the labor force, along with the creative destruction of existing plants, equipment and processes. Innovation and competition lower inflation, which benefits the broad population, but high returns on capital accrue disproportionately to those who have capital. In a nutshell, you get the Internet, iPhone and low prices, while workers are displaced and the wealthy become wealthier. We’ve been in the efficiency cycle for almost 40 years.

In contrast, with an “equality”-focused economy, tax rates and regulations rise, lowering incentives to innovate. Competition declines as a more rigid regulatory framework gains prominence. New product development declines, employment becomes more predictable and there’s less obsolescence. Global trade slows, creating more inflation. The income gap narrows between the wealthy and the poor. Here we see much longer cycles between the new iPhones, and they’re even more expensive with fewer meaningful upgrades. The retail industry is less threatened by Amazonian forces and participation in the labor market can stabilize and even grow. We may be heading into this environment. The chart on the next page illustrates the efficiency/equality transition.

A transition from efficiency to equality will take time and transcend several election cycles. The speed and depth of the transition are difficult to predict, but we feel the political parties are likely to feel ongoing pressure to change the established system of efficiency. Too many voters feel as though the current environment is unacceptable. Politicians and parties will adjust or lose their positions of governance.

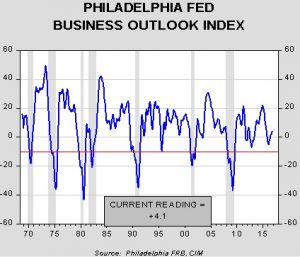

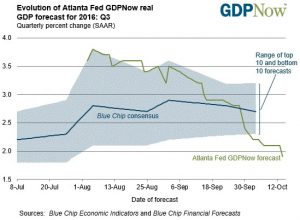

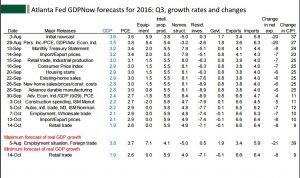

Although we may be at the beginning of a transition, we don’t believe it’s likely to create a recession over our projected forecast period of three years. On that front, we believe Fed policy is more immediately relevant. Although the Fed has telegraphed a moderate pace of raising rates, forward interest rates indicate a broad expectation that the Fed will go even slower. In this instance, our expectations are more aligned with the market, and we believe the economy is likely to continue along its path of slow growth for quite a while.

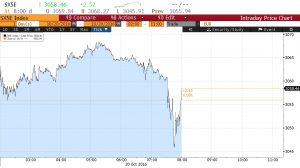

STOCK MARKET OUTLOOK

Although the aforementioned transition to equality may lower growth in corporate profits and increase inflation, we expect a gradual pace of change, allowing equities to perform reasonably well. Looking forward, we believe the return/risk profile of stocks is generally constructive and we continue to diversify across capitalization sizes. This quarter we trim the small cap exposure in some portfolios, recognizing its recent strong performance. We are also beginning to utilize emerging market equities across more portfolios as we see potential upside from favorable currency trends and low valuations. Still, emerging market equities are highly volatile, so we utilize only a limited allocation, except where risk tolerance is high.

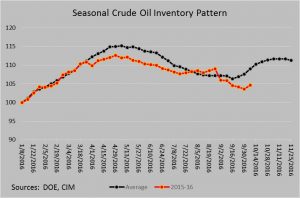

With regard to our large cap sector weights, we remain overweight energy but pare back the exposure after the sector’s very strong performance. We are also overweight the technology, industrial and consumer discretionary sectors, while being underweight financials, utilities and telecom. (We continue to allocate to real estate as a separate asset class; see comments in the Other Markets section below.) These sector views are formed from our work on valuations and industry fundamentals. Our growth/value posture remains at 60/40.

BOND MARKET OUTLOOK

As the economy shifts from efficiency to equality, we will be keeping close tabs on inflation, which tends to create significant risks for bond investors. However, we do not anticipate inflation to emerge quickly or without a measure of warning. Excess global supply capacity remains high for many industries and inflation is unlikely to build unless global trade is dialed down. Such a trend is possible but not yet in place. Accordingly, we continue to believe bond investors can utilize a combination of short, intermediate and long maturities in their portfolios. Bonds continue to provide excellent diversification and can help to address market volatility when combined with other asset classes.

At this point we do not anticipate a recession and do not expect large increases in bond defaults. Therefore, we continue to believe corporate bonds are relatively attractive. Still, our focus remains on investment grade corporate bonds, which we prefer over speculative grade bonds.

OTHER MARKETS

We expect real estate fundamentals to remain generally strong and believe this asset class can benefit from ongoing low interest rates. Still, this asset class has performed very well and we trim the exposure in some portfolios this quarter. Looking forward, the return/risk remains attractive, particularly where income is an objective.

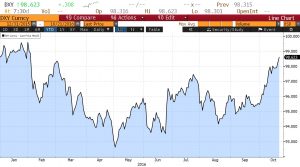

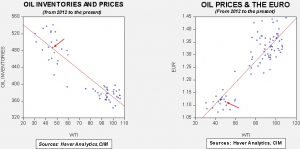

Commodities continue to provide diversification and we focus our commodities allocation on gold. Gold helps to address some of the risks emerging from global central bank policies aimed at depreciating currencies. This precious metal can also help address certain geopolitical risks and can perform well in the event the U.S. dollar weakens relative to other major currencies.

View the complete PDF