by Asset Allocation Committee

My weekend exercise is to take my dogs on long walks. Both dogs seem to enjoy these walks and I use the time to listen to podcasts. I recently listened to a long podcast that interviewed Sebastian Mallaby, a British journalist and senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. He has recently written a biography on Alan Greenspan, titled The Man Who Knew. The FT Alphachat podcast[1] was an interview about that book.

Although I haven’t read the book yet (it’s on the list), a key takeaway from the podcast was that one of Greenspan’s attributes was that he was a savvy political operative. He understood that the Federal Reserve operates in a political environment and that one of the Chair’s jobs is to manage the political system to maintain the central bank’s independence. Mallaby suggested in the podcast that Greenspan was truly a “maestro” in managing the political situation. However, as I listened, I wondered if managing the political situation meant that monetary policy was being framed to please the politically powerful.

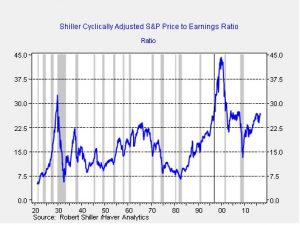

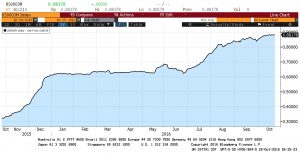

This chart shows the Shiller Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings ratio (CAPE). We have placed a vertical line at December 1996 when Greenspan gave his famous “irrational exuberance” speech, raising questions about equity market valuations. As the chart shows, the CAPE was approaching levels near the peak of the 1929 stock market bubble that was soon followed with a massive market crash. Although Greenspan didn’t suggest that the Fed was about to change monetary policy to curb asset prices, equity markets around the world fell sharply on fears that Greenspan was about to use monetary policy to lower the stock market. Greenspan faced heavy criticism for the speech.[2] Being the consummate political operator, Greenspan’s Fed policy seemed to evolve into a form where asset market bubbles cannot be established in advance and the job of the central bank was to use monetary policy to repair the damage wrought to the real economy once the bubble collapses.

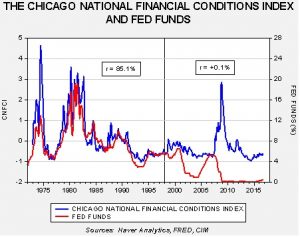

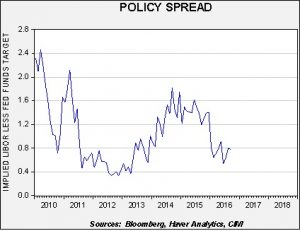

This chart overlays the Chicago FRB National Financial Conditions Index and the fed funds rate. The index measures stress in the financial system. The higher the reading, the greater the stress in the system.

The two series were closely correlated (85.1%) from 1973 through 1997, until the financial conditions index was created in 1998. When fed funds rates rose, financial conditions deteriorated. In some respects, financial conditions acted as a “force multiplier” for policy. But, from 1998 to the present, the two series have become virtually independent. After hearing Mallaby’s podcast, we suspect the FOMC may be trying to keep financial conditions calm, which could be construed as a reading under zero on the above chart.

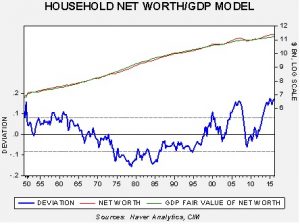

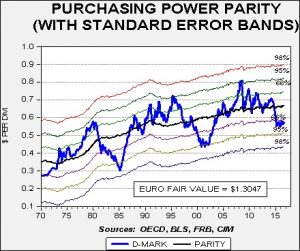

This chart shows a model of household net worth regressed against nominal GDP. Both series have been log-transformed. Net worth was elevated into the early 1960s but steadily declined into the late 1970s. It began to rise in 1995. Note that since 1998, net worth has generally outpaced GDP except during recessions.

Currently, net worth relative to GDP is elevated. It does appear that these increases in net worth that outpace the overall growth of the economy could be a function of monetary policy. As investors become confident that the Federal Reserve will continue to suppress financial stress, it appears there is a tendency for asset prices to rise to lofty levels. When valuations become unsustainable, often at the turn of the business cycle, it appears that sharp declines in net worth, caused by price declines in real and financial assets, leads to a fall in household net worth.

Mallaby’s research of Greenspan suggests he was inclined to allow asset prices to rise while striving to contain price inflation. It is arguable that Greenspan’s policies with regard to financial system stress have been adopted by his successors. If so, monetary policy is probably (although perhaps inadvertently) designed to aid asset prices. As the last chart shows, net worth is elevated again at levels that have been difficult to sustain in the past. We still believe that recessions are the primary triggers of market corrections and we closely monitor the economy for such events. The current level of valuation makes this exercise even more critical.

______________________

[1] http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2016/10/21/2177678/podcast-our-chat-with-sebastian-mallaby-on-alan-greenspan/