by Bill O’Grady, Kaisa Stucke, and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EST] Happy Valentine’s Day!

For a mostly quiet market day there is a lot of news to digest. Let’s get started!

Flynn out: Yesterday, when Kellyanne Conway suggested that National Security Director Flynn had the full support of the president, we suspected he was doomed. We have all seen this vote of confidence just before someone gets ousted (most often in sports—when a general manager or owner gives a coach or field manager his “full confidence,” he is usually gone soon after). We see two takeaways from this situation that affect markets. First, Flynn’s short tenure and the circumstances of his resignation suggest a chaotic and mismanaged White House. It isn’t unique to Trump; most new administrations have the air of confusion for at least three to six months. However, given Trump’s lack of military or government experience, worries about his ability to manage the government are elevated and so this resignation adds to fears that the incoming president will struggle. And, the more he seems unable to control his message or policy path, the less confidence the markets will have in his ability to get anything accomplished. Second, Mike Allen at Axios has developed a useful taxonomy for the administration’s tensions when he describes it as the “confrontationalists” versus the “conformists.” The former, which include Bannon, Conway, Sessions and Miller, want to confront the Washington system and make aggressive moves on both foreign and domestic policy. We have characterized these members as populists. The conformists are the Kushners, Preibus, Cohn, Mattis and Tillerson, who want to execute the president’s policies within the framework of Washington. We have characterized this group as establishment. Flynn was a confrontationalist and the replacement names would fall into the conformist category, so the former team is losing a position.

If one backs away from the noise surrounding Flynn, there are a couple of oddities. First, Flynn would have known that his calls were being monitored. He had deep experience in intelligence and should have been shocked if the conversations weren’t being taped. The fact that he seemed to have multiple conversations does suggest that he, and his Russian counterpart, may have been consulting superiors. Second, although the Logan Act could be in play, which makes it illegal for private citizens to negotiate for the U.S., in fact, private citizens are involved in these sorts of things all the time. When a business leader talks to a foreign leader about investment in a foreign nation, there are potentially policy issues involved. Few people have ever been indicted under the act and no one has ever been prosecuted.[1] Thus, the threat of “blackmail” is probably not all that strong. Think of it this way; if the Logan Act was strictly enforced, no new administration could make contact with foreign governments. That doesn’t make much sense.

Instead, we suspect that Flynn was trying to create a policy that would be favorable to Russia in return for cooperation against IS. This is likely a fool’s errand; Russia’s primary goal in the region is to boost its influence through supporting Assad and IS hasn’t been a serious threat to the Syrian leader. It is quite possible that Mattis and Tillerson don’t support this deal with Russia and opposed Flynn trying to engineer it. Clearly, Flynn putting the vice president in a bad light is a real problem, but what we may be seeing here is simply a fight over policy and the conformists won.

Our take has been that Trump needs to placate both constituencies. The person that could prove to be the most powerful person beside the president is the one who shows him the path to this end. It isn’t obvious to us who that person will be, although if we had to bet, we are watching Jared Kushner. The equity markets and the dollar are rooting for the conformists. They would represent establishment policy goals and support low inflation.

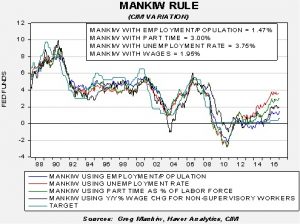

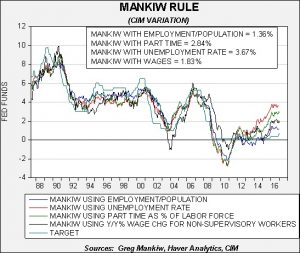

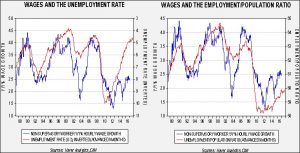

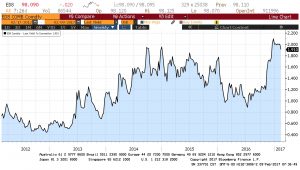

Yellen to Congress: The Fed chair goes to Capitol Hill for her semiannual testimony. Currently, the fed funds futures put the odds of a March rate hike at 30%. Although we don’t think the case for a rate hike is all that strong, we suspect Yellen would like the flexibility to raise rates in March even if the board decides to stand pat. Thus, we would not be shocked to see a rather hawkish speech today even if the FOMC decides not to hike next month.

Is Merkel in trouble? Reuters is reporting that the three leftist parties in Germany probably have enough support to form a government. Current polls suggest the SPD and Greens have about 38% support in the electorate; to form a government, the SPD would have to accept the hard-left Linke Party, which is seeing 10% support. Given proportional voting rules, 48% would probably be enough to form a narrow majority in the Bundestag. The key question is whether or not the SPD, a center-left party, could accept a coalition with the Linke. The latter wants to pull out of NATO, is open to a new security agreement with Russia and wants the removal of all U.S. bases from Europe. It also supports debt relief for European nations. We suspect the SPD would rather join with Merkel’s coalition but would want a much larger profile in the new government.

Kim Jong-nam dies: According to numerous media sources, Kim Jong-un’s estranged older brother, Kim Jong-nam, has died in Malaysia. Although unconfirmed, it does appear he may have been poisoned, supposedly by North Korean operatives. The elder Kim had been critical of his sibling’s government; if he was assassinated, it adds to evidence of the brutality of the North Korean regime.

View the complete PDF

_____________________________________

[1] https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33265.pdf