by Bill O’Grady, Kaisa Stucke, and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] It’s May Day, the international labor day. As noted above, a large number of financial markets are closed today, including China and most European markets. Direct news flow is less than normal due to the closed markets. Here are the items of note:

See you in September: Congressional negotiators reached an agreement to fund the government into autumn when the debt ceiling will be hit and a broader spending package will be required. The vote is expected to be held early this week. There is $12.5 bn of new military spending and $1.5 bn for border security, although no wall money was allocated. The border spending only covers technology and repair to existing structures. Democrats were able to spare spending for Planned Parenthood, money to pay for Medicaid for Puerto Rico and a modest $100 mm for opioid addition reduction.

China’s PMI data a bit soft: China’s PMI data came in a bit soft at 51.2. We have been watching steadily tightening policy in China and this may be an early sign that policy is starting to “bite.”

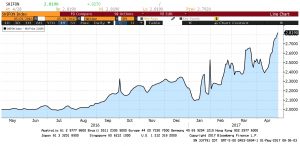

This chart shows the overnight Shanghai LIBOR. Since the January trough, rates are up just over 70 bps. It is something of a surprise that policymakers are tightening policy into the October CPC meetings. We have speculated that Chairman Xi wants to see a robust economy as he kicks off his second term. The best explanation for tightening policy is growing concern over rising debt and non-performing loans. China can achieve any growth it wants; it has an investment-driven growth model and so debt levels are the only constraints. The problem with determining debt capacity is that it really can’t be established ex ante; it can only be established ex post. In other words, the debt limit is discovered when a debt crisis occurs. Until the crisis, no one really knows. It is no great secret that China needs to change its model to drive growth from consumption. The transition will (a) mean periods of lower growth, and (b) weaken the power of those who have benefited from the current investment model.

The FOMC meets on Wednesday: We don’t expect any policy changes. This meeting doesn’t have a press conference and lately the central bank seems to reserve changes for meetings with such conferences. We will be watching for signs that the FOMC is teeing up for a June rate hike, but a lack of signal doesn’t mean that a hike won’t come. After all, there wasn’t anything in the January meeting statement that hinted at a March rise. The financial markets might take the lack of signal as an indicator that a hike is not coming soon, which would probably be a mistake. We do look for the Fed to acknowledge that some of the economic data has softened, but we also expect the committee to suggest that the slowing is temporary.

Matteo Renzi wins back party leadership: Renzi, the former PM of Italy, stepped down last year when he failed to pass political reform proposals. He ran to lead the Democratic Party and won the leadership vote with 72% of the ballots cast. Although Renzi is clearly popular within his party, the populist Five Star Movement continues to lead in the polls with 30% of the electorate. Similar to the Netherlands, it isn’t clear whether the Five Star Movement can form a government as it’s possible no other party will work with it. National elections are expected in February 2018; this may be the most risky election for the Eurozone in the next 12 months.

Other European elections: In France, Macron continues to hold a dominating lead. The latest polls show 60% support for Macron compared to 40% for Le Pen. Although there are still reasons to worry about Sunday’s election (e.g., preference falsification may be overstating Macron’s support; the wide margin may lead to complacency and a low turnout, which would help Le Pen), overcoming 20 points in less than a week would be unprecedented in modern Western elections. As we noted last week, Truman overcame such differences but it took him about two months. We would not be shocked to see a tighter final vote; 55% for Macron to 45% for Le Pen would be a likely outcome, but a Le Pen victory would be a shocker. Meanwhile, in Germany, the recent gains by Socialist Party candidate Martin Schulz are evaporating as Merkel’s lead has widened by eight points to 37%. The most likely outcome for forming a government remains a “grand coalition” of the Socialists and the Christian Democrats/Christian Social Union. The Greens and the Left Party are unlikely coalition candidates and the Free Democrats, often a junior coalition partner for the CDU/CSU, probably won’t get enough votes to form a government. Still, a Merkel win in September will be seen as good for markets.

Other items: Although the media focus continues around the 100-day mark for the Trump administration, we noted a couple of good weekend editorials. The NYT carried an op-ed by R.R. Reno suggesting that the Reagan era is over and the GOP is rapidly becoming a nationalist party.[1] This is a theme we have been discussing since 2014; the U.S. two-party system is one of forced coalitions and these coalitions are currently in flux. The cosmopolitan elites, who have benefited from globalization and deregulation, are becoming less welcome in the evolving GOP. We note a comment from The Hill that suggests the political obituaries for Steve Bannon were probably premature; economic nationalism has been a focus of the president’s recent speeches.[2] The FT noted in a similar op-ed that Sen. Sanders (I-VT) is now the most popular politician in the U.S.[3] Rana Foroohar notes that voter concerns are mostly economic. She also notes the leadership of the Democrat Party is remarkably ignoring this trend. We are reminded of the German sociologist Max Weber who made a distinction between class and status. Class is determined by income and wealth, while status is the social group(s) to which one belongs. Since Clinton, the Democrat Party has become less of a party of class and more of a party of status. In other words, the party has focused on helping a status group’s power through regulation, which gives rise to its focus on racial and gender rights. However, the Democrats have increasingly ignored class, becoming the party that supports technological disruption. Status rights are important but, in the current environment, not as important as class. Donald Trump is recreating the GOP into a working-class party, which may become uncomfortable for some elements of the business class currently in that party’s coalition. We don’t know how this is going to shake out but it does appear the coalitions are shifting and what defines a Democrat or Republican in the coming years may be much different than what defines them currently.

________________________________________

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/28/opinion/sunday/republicans-are-now-the-america-first-party.html (paywall)

[2] http://thehill.com/homenews/administration/330987-bannon-reasserts-influence-in-100-days-push

[3] https://www.ft.com/content/b34f5536-2c02-11e7-bc4b-5528796fe35c (paywall)