Tag: nuclear

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Implications of the Israel-Iran Conflict (July 28, 2025)

by Daniel Ortwerth, CFA | PDF

During the night of June 13, an already unsettled Middle East was shocked to a new level of unrest when bombs from an Israeli airstrike rained down on Iran’s key nuclear and military facilities. In what proved to be the opening salvo of a 12-Day War, which included the first use of “bunker-buster” bombs by the United States, Israel asserted that the barrage was necessary before its adversary could get any closer to building an atomic weapon. In an already tense and conflict-ridden region, questions abound as to how this conflict will affect the Middle East’s balance of power and the region’s relations with the rest of the world. With Iran’s nuclear program at the center of the conflict and the future of its government in question, a heightened sense of risk and uncertainty looms large over the deliberations of global leaders.

This report provides an overview of the war and discusses where things stand now (at least as of our publication date). The report also addresses the conflict’s likely impact on the Middle Eastern balance of power and examines its possible long-term regional effects. As always, we conclude with investment implications.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Podcast – #66 “Update on the US-China Military Balance of Power” (Posted 5/16/25)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Update on the US-China Military Balance of Power (May 12, 2025)

by Daniel Ortwerth, CFA | PDF

In early 2021, we published a series of reports assessing the overall balance of power between the United States and China in military, economic, and diplomatic terms. In early 2023, we provided an update to our analysis. The current report is the next in what we intend to be a biennial series on the subject. Looking comprehensively at both countries’ power and sources of power, we assess that, while the US retains the greater military capacity to influence the world and protect its interests, China continues to close the gap, perhaps at an accelerating pace. For example, China continues to expand its lead in the number of combat-capable ships in its navy, it has gained valuable operational experience, and it can deploy enormous forces to the South China Sea, the East China Sea, and the Taiwan Strait. China’s coastal military forces are now strong enough to potentially deter the US from intervening in a crisis around Taiwan.

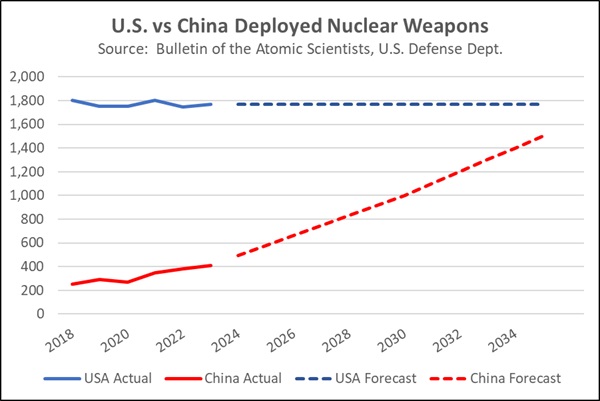

In this report, we provide an update to the numerical comparison and our analysis of China’s military development over the last two years. We emphasize critical areas such as China’s continuing buildup of its strategic nuclear arsenal and how that could spur a destabilizing new global arms race. We conclude with the implications for investors.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #117 “The Incremental Uranium Demand for Weapons” (Posted 4/15/24)

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – The Incremental Uranium Demand for Weapons (April 15, 2024)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

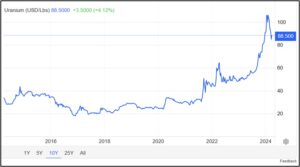

In our Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly report from March 4, 2024, we began to explain more fully our recent decision to introduce uranium and uranium miners into our Asset Allocation strategies. Our key thesis was that current and planned investments in new nuclear reactors for electricity generation, especially in China and India, will likely lead to booming demand for uranium in the coming decades, while supplies are likely to be constrained. This theory is increasingly discussed among investors, and we think it’s a key reason for the jump in spot uranium prices since 2022, as shown in the chart below. In this report, we discuss a less-recognized source of incremental uranium demand that could drive prices even higher: China’s ongoing rapid expansion in its arsenal of nuclear weapons and the possibility of a global nuclear arms race in the future.

After decades of keeping only a “minimal” nuclear deterrent of about 200 warheads, China has recently begun a dramatic expansion of its arsenal. Western analysts believe China’s arsenal has expanded by about 42 warheads annually since 2020, reaching 500 warheads in 2024. Publicly observable and classified evidence suggests Beijing aims to match the United States’s deployed arsenal of 1,770 warheads by 2035 (not including reserves), which would imply adding an average of 115 warheads per year until then. Finally, as we have written elsewhere, we think rising geopolitical tensions around the globe and growing doubts about the US’s commitment to its allies could potentially prompt a dozen or more non-nuclear states to develop nuclear weapons in the coming decade or two. If that results in a global nuclear arms race, the world could end up producing several hundred new nuclear warheads each year.

In every scenario we’ve looked at, China would be the main driver of new nuclear weapons production in the years to come. So, in order to understand the incremental uranium demand for weapons, we will focus on China’s expected needs. Because of China’s long nuclear history and technological prowess, we assume its nukes are similar to the advanced, plutonium-based hydrogen bombs fielded by the US and Russia. According to a 1999 declassification guide from the Department of Energy, such bombs can theoretically be made with just 6 kg of plutonium, similar to the mass of fissile material for a uranium-based bomb. Another DOE report says that the US has used 3.4 metric tons of plutonium in its 1,054 nuclear tests since World War II, implying the use of about 3.25 kg per test. Actual weapons probably use more plutonium than the hypothetical minimum or test levels, so we assume current and future Chinese bombs would use at least 10 kg of plutonium each. Data on weapons-grade uranium and plutonium stocks from the International Panel on Fissile Materials suggests modern hydrogen bombs encompass an average of about 15 kg of plutonium each, which we use in our calculations below.

Of course, very little plutonium occurs naturally on Earth; it is generally made from uranium. Open-source reports indicate that producing 1 kg of plutonium takes about 4,000 kg of uranium. If these reports are accurate, each new Chinese warhead requires about 60 tons of uranium, and China’s current annual production of about 42 warheads probably represents about 2,520 tons of uranium. Unclassified sources don’t clarify what form of uranium is used in the 1:4,000 ratio, but if it is standard uranium mine output (i.e., “yellowcake,” or minimally processed ore consisting of about 85% triuranium octoxide), then China’s current annual nuclear weapons output is using the equivalent of 4.2% of the approximately 60,000 tons of uranium that was produced by mines around the world in 2023. We therefore suspect that China’s current nuclear build-up is probably helping to buoy spot uranium prices even today.

Looking forward, if China increases its bomb output to the expected 115 per year, its nuclear program would require at least 11.5% of 2023’s global mine output and would more obviously put upward pressure on uranium prices. Moreover, we believe our estimates could be quite conservative. For example, it may be that the plutonium/uranium ratio of 1:4,000 refers to pure or enriched uranium, which would imply that even greater quantities of uranium ore are needed. China might also decide to build up an inventory of reserve warheads, further boosting the need for uranium ore. Plutonium and uranium production waste may also boost uranium needs. Finally, if geopolitical tensions do result in a global nuclear arms race, we believe the total uranium demand from China, Russia, the US, all other existing nuclear states, and new nuclear states could easily overwhelm global supplies and send long-term uranium spot prices dramatically higher.