Tag: China

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Mid-Year Geopolitical Outlook: Searching for the Endgames (July 14, 2025)

by the Confluence Macroeconomic Team | PDF

As the first half of 2025 draws to a close, we typically update our geopolitical outlook for the remainder of the year. This report is less a series of predictions as it is a list of potential geopolitical issues that we believe will dominate the international landscape for the rest of 2025. The report is not designed to be exhaustive. Rather, it focuses on the “big picture” conditions that we think will affect policy and markets going forward. Our issues are listed in order of importance.

Issue #1: US-China Tensions Remain

Issue #2: Russian-Ukraine War Continues

Issue #3: Fallout From Israel-Iran War

Issue #4: US Mulls Capital Controls

Issue #5: Prospects for Lasting Economic Change in Europe

Issue #6: AI Investing Gets Second Wind

The podcast episode for this particular edition will be posted under the Confluence of Ideas series later in the week.

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Podcast – #66 “Update on the US-China Military Balance of Power” (Posted 5/16/25)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Update on the US-China Military Balance of Power (May 12, 2025)

by Daniel Ortwerth, CFA | PDF

In early 2021, we published a series of reports assessing the overall balance of power between the United States and China in military, economic, and diplomatic terms. In early 2023, we provided an update to our analysis. The current report is the next in what we intend to be a biennial series on the subject. Looking comprehensively at both countries’ power and sources of power, we assess that, while the US retains the greater military capacity to influence the world and protect its interests, China continues to close the gap, perhaps at an accelerating pace. For example, China continues to expand its lead in the number of combat-capable ships in its navy, it has gained valuable operational experience, and it can deploy enormous forces to the South China Sea, the East China Sea, and the Taiwan Strait. China’s coastal military forces are now strong enough to potentially deter the US from intervening in a crisis around Taiwan.

In this report, we provide an update to the numerical comparison and our analysis of China’s military development over the last two years. We emphasize critical areas such as China’s continuing buildup of its strategic nuclear arsenal and how that could spur a destabilizing new global arms race. We conclude with the implications for investors.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – The US Geopolitical and Economic Bloc as an Investment Region (August 5, 2024)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

More than a decade ago, we at Confluence began describing how United States voters have become more reluctant to shoulder the costs of global hegemony. We’ve shown how increased populist isolationism in the US and other Western nations helped embolden Chinese General Secretary Xi, Russian President Putin, and other revisionist authoritarians to become more assertive in their efforts to undermine the US-led world order. As the resulting geopolitical tensions prompted leaders around the world to seek military, economic, and cultural allies to preserve their security and prosperity, we noted a clear fracturing of the world into relatively separate geopolitical and economic groups or “blocs.” We think this global fracturing is bound to have big implications for investors.

To better understand the new blocs and gauge how they might impact investors, we developed an objective, quantitative method to predict which bloc a country would adhere to in the coming years. We first published our findings in our Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report from May 9, 2022. In our report today, we update the analysis. We will also do a deep dive into the attractiveness of the US bloc as an investment region, the prospects for the bloc staying together after the US elections in November, and the implications for investment strategy.

Note: There will be no accompanying podcast for this report.

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Podcast – #51 “Meet Ferdinand Marcos Jr., President of the Philippines” (Posted 7/22/24)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Meet Ferdinand Marcos Jr., President of the Philippines (July 22, 2024)

by Daniel Ortwerth, CFA | PDF

Seven short weeks ago, we published a report on the brewing tensions between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea, focusing on their dispute over the Second Thomas Shoal. Despite the tight time interval since that report, the brisk pace of continuing developments in the area and the ever-present risk of escalation bid us to return to the subject. This time we direct our attention to a key individual who sits at the focal point of the crisis: Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the president of the Philippines.

This report begins with a quick review of the geopolitical context that makes the Philippines-China dispute so important. We then outline the life and career of President Marcos Jr., and we review the relevant elements of the broader Philippine political landscape. Within that context, we will explain the key traits and actions of President Marcos Jr. as they relate to the present geopolitical concern, followed by an assessment of his likely course of action. Finally, we update the investment implications from the previous report.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #122 “A New Factor for Gold Prices” (Posted 7/15/24)

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – A New Factor for Gold Prices (July 15, 2024)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

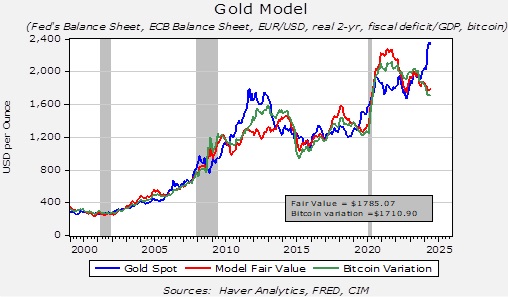

The standard regression model is as follows:

Y = α +β(X) + ε

Where Y is the dependent variable, X is the independent variable, α is the intercept, β is slope and ε is the error term. No model, no matter how many independent variables are added, can capture the complete relationship to the dependent variable. However, a well-constructed model will account for most of the variation in the behavior of the dependent variable.

Although it tends to get short shrift in statistics classes, the error term is rather interesting, especially with regard to time series models. Essentially, the error term, or epsilon, is where the unspecified causal factors that affect the dependent variable are housed. The goal of modeling is to select the most meaningful independent variables and then assume the ones that are not specified are not important enough to dramatically affect the dependent variable. It may be that the unspecified terms are not all that important, or if they are, they are offset by other unspecified variables so that the model’s performance isn’t adversely affected.

Sometimes, a dependent variable begins to exhibit deviations to the model’s estimate; this may be caused by several factors. One is that the relationship between an already specified independent variable and the dependent variable has changed. The relationship may have rested on some other factor, such as policy, that has made it more or less important. Over time, the β, or the correlation coefficient, will adjust to this new relationship. In other cases, a previously unimportant variable, contained in epsilon, becomes important.

We think this latter situation is affecting the gold market.

The chart above is our basic gold price model. As the chart shows, the model’s estimation occasionally deviates from the actual price. If nothing has changed, this deviation may suggest an over or undervalued market. The recent spike in gold prices is clearly running well above our model’s estimation. However, we think we have isolated a change that accounts for this deviation.

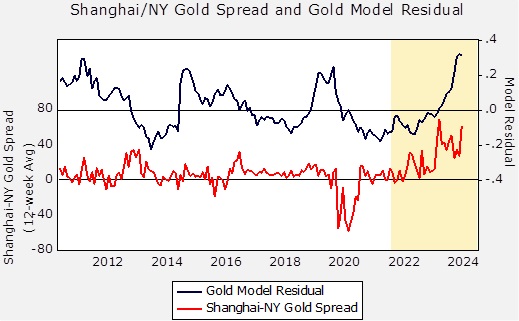

The upper line on the above chart shows the model’s residuals since 2012. The lower line shows the spread between gold prices in Shanghai and New York. The history of this spread shows some deviation, but in general, this condition invites arbitrage if prices are higher or lower in one market compared to the other. Note that the New York prices far exceeded those in Shanghai during the pandemic. We can assume the mechanisms for arbitraging that market were disrupted by the pandemic, and the spread narrowed when these mechanisms returned. The area on the chart above in yellow indicates the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Note that gold prices in Shanghai have been persistently elevated relative to those of New York.

The G-7 implemented sanctions on Russia in the wake of the invasion, and perhaps the most draconian of those was the move to freeze Russian foreign reserves. This move raised fears in other nations that if they were to see relations with the US deteriorate, then similar actions might be deployed against them as well. So, in response, foreign governments have been increasing their gold purchases. Since the Chinese are concerned about the vulnerability of their massive US Treasury holdings, it appears they have been aggressively buying gold to the point where the Shanghai price has been persistently above the New York price.

It’s still too early to determine what impact this spread relationship will have on the overall gold price in the future, but this situation is a good example of when a previously quiescent variable, well contained in epsilon, suddenly becomes important. Faced with a model that is deviating from its past performance, the challenge for the analyst is to determine the cause. We believe that Asian buying, both from central banks and private investors, is the cause in this case. This condition could mean that when traditional bullish conditions for gold return (e.g., lower interest rates, weaker dollar, central bank balance sheet expansion), the price of gold could move sharply higher, bolstered by this new factor — enhanced Asian buying.