by Bill O’Grady and Kaisa Stucke

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] After a rally in risk assets yesterday, we are seeing a reversal this morning. Although China’s official PMI data came in a bit soft (see below), we suspect the real story continues to come from the forex markets. Overnight, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), the country’s central bank, surprised the markets by cutting its policy rate to a record low of 1.75%. A Bloomberg survey showed that 12 economists out of the 27 polled had forecast a cut in rates. The bank cited low inflation as the reason. We have our doubts.

This chart shows the market’s reaction to the rate cut. The AUD is quoted in USD per AUD, meaning the higher the reading the stronger the AUD. Note the sharp decline in light of the unexpected rate action by the RBA.

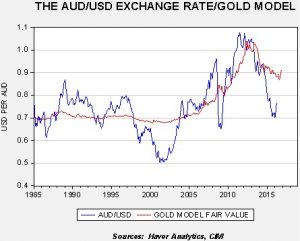

Here is a longer term look at the data.

This is a five-year chart of the USD/AUD exchange rate. The AUD fell sharply as commodity prices began to decline in 2014. During China’s stronger growth period into mid-2013, the AUD traded above $1.00. It slipped under 70 cents in Q3 2015 and has been bouncing around 70 cents until recently, when the currency began to appreciate.

We are coming to the position that no central bank or financial authority on planet Earth wants a stronger currency. Every nation is trying to engage in some sort of accommodative policy and an appreciating currency tends to undermine those efforts. The AUD has bounced, in part, due to Chinese stimulus. In fact, there is a positive relationship (r=76.7%) between gold and the AUD (with gold leading the currency by about eight months), and so this may be a move by the RBA to preempt further appreciation.

Although deviations this wide are not unprecedented, history suggests that such deviations tend to get corrected by an appreciating AUD. The recent rally in gold (seen by the late rise in the red line) makes the bullish case for the AUD even stronger. We suspect that Australian authorities do not want a stronger currency and thus are taking steps to weaken it by cutting rates.

If our thesis is correct, we should see the Eurozone and Japan take steps to address the recent strength in the EUR and JPY. Reuters reported yesterday that BOJ Governor Kuroda expressed concern about JPY strength, which was given as a reason for yesterday’s strength. We note today that comments out of Japan suggest that NIRP is very unpopular, meaning the BOJ may be forced into other stimulus measures, which might include even bigger QE, currency intervention (very controversial) or considerations of “monetary financing of fiscal spending,” or “helicopter money” in the vernacular.[1] We look for ECB President Draghi to react to recent EUR strength as well. Additionally, it appears to us that the Fed won’t really move rates higher without assurances that tightening policy won’t lead to a much stronger dollar…which it undoubtedly will. All of this means that easy policies will remain in place everywhere and currency depreciation may be the only tool left that will measurably lead to stronger growth. However, as the 1930s showed, everyone cannot have a weaker currency.

_______________________

[1] See this week’s WGR and the following two weeks’ WGRs.