by Bill O’Grady, Kaisa Stucke, and Thomas Wash

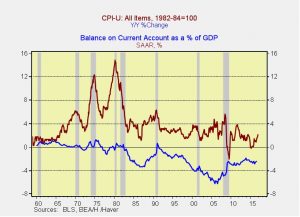

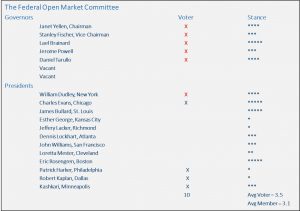

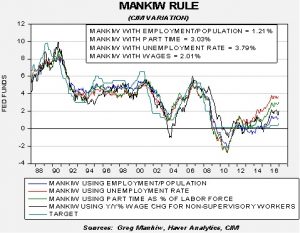

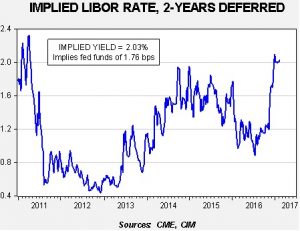

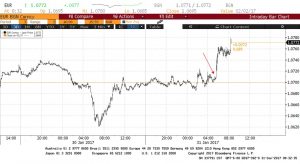

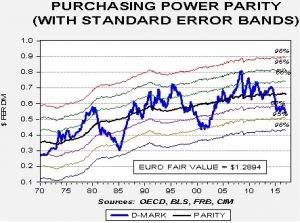

[Posted: 9:30 AM EST] We are seeing the dollar rise this morning along with U.S. equity futures. There isn’t a lot of news to indicate a reason for the rise in the greenback. Perhaps the best explanation is that the drop we have seen in the dollar over the past two weeks has mostly been a technical correction. Momentum indicators, such as the moving-average convergence/divergence indicator and the stochastic indicator, became overbought, suggesting that the market had gotten ahead of itself. Since mid-January, we have seen the market move from overbought to oversold, and chart traders have probably concluded that the short trade has reached its limit. Although the dollar is overvalued based on inflation differentials, expectations of tighter monetary policy (Dallas FRB President Harker suggested yesterday that March could be a “live meeting”), fiscal expansion and tax reform (the big one being the border adjustment) all point to a stronger greenback.

It appears that the recent U.S. operation in Yemen had a bigger target—Qassim al-Rimi, the head of al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. He apparently survived and is now taunting President Trump. Operations to remove leaders from terrorist groups have been part of the war against these groups since 9/11. However, this action in Yemen does bear watching. There has been growing speculation that the U.S. is taking a tougher stand against Iran and there is a temptation to view the proxy war in Yemen as a Saudi/Iranian conflict. Specifically, National Security Advisor Flynn has been openly hostile to Iran, saying “the days of turning a blind eye to Iran’s hostile and belligerent actions” have come to an end and he has also blamed Iran for Houthi actions against U.S. allies, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Although there are elements of a proxy war, the overall conflict is local. Yemen has struggled to unify for years. In fact, from 1967 to 1990, Yemen was divided into North Yemen and South Yemen.

There are echoes of this division in the current conflict; in fact, the Houthi military actions are more tribal in nature. Still, our worry is that the Trump administration could be lured into a quagmire in Yemen as a way of indirectly attacking Iran. Simply put, escalating the conflict in Yemen would probably be a distraction and “winning” (an undefined outcome at this point) would not significantly undermine Iran.

China’s foreign exchange reserves fell by $12.3 bn in January, a bit more than forecast.

This chart shows China’s forex reserves since 2000. They peaked in mid-2014 and have steadily declined ever since. We have seen the level dip under $3.0 trillion, which, being a large round number, is psychologically significant. However, as the chart shows, the recent decline is simply part of a longer trend. Why are reserves falling? One of the key reasons is that the PBOC is trying to prop up the value of the CNY. Without support, the Chinese currency would be weaker. Second, falling reserves could signal capital flight; as Chinese citizens move their assets out of China, it lowers the nation’s reserves. China has been clamping down on capital flows which may account for the slower drain of reserves but the overall trend is probably lower. Is this necessarily a bad thing? Not completely. The buildup of reserves reflected a deliberate policy to use export promotion for development. If China is restructuring toward consumption, then this level of forex reserves is probably unnecessary. If, however, the drop in reserves is mostly due to capital flight, then it is a worry because it suggests that Chinese investors are unhappy with developments in the Chinese economy and political system.