by Bill O’Grady and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] It’s the Ides of March! Be careful out there. Markets were very quiet overnight. Here is what we are watching:

Trump 2.0: As expected, Larry Kudlow is replacing Gary Cohn as NEC director. This should be a somewhat market supportive appointment. Kudlow isn’t an economic heavyweight; he doesn’t have a degree in the subject and his claim to fame is mostly as a supply side pundit. On the plus side, he is a skilled media spokesman and will improve the profile of the administration, whereas Cohn could be a bit stiff in front of the cameras. Kudlow will be in his element. We doubt he will push back too hard against the president’s policies but we do expect him to frame the policies as pro-growth and pro-market. Contorting trade impediments into being pro-growth and pro-market will be a feat but, if anyone can do it, Larry is the best candidate. He has already come out in favor of a “strong dollar” in a public statement; the forex markets ignored his comments. Kudlow likely assumes the strong dollar of the early 1980s was due to supply side economic policies. We doubt they played a major role; a more important part was played by Paul Volcker’s tight money policies. But, returning to allowing the markets to set exchange rates is a better policy stance than Treasury Secretary Mnuchin’s comments at Davos.

There are reports[1] that the president is preparing to replace more of his cabinet and aides, including Chief of Staff Kelly, National Security Director McMaster and AG Sessions. Financial markets have not reacted well to previous departures, although we expect the impact will decline over time. As we noted yesterday, this is a normal pattern that presidents follow. They usually attract strong characters in the first year but by the time their first four years end presidents tend to surrounded themselves with people who can execute the president’s plans, not comment on the plans themselves.

Russia and Britain: We are still awaiting Russia’s official response but the commentary has been denial and contempt. Russia is trying to portray itself as a great power and actions like executing old double agents are part of that narrative. The U.S., Germany and France have joined the chorus demanding that Russia accept responsibility for the attack, although we note it hasn’t been a universal position. In France, a spokesman suggested Britain’s proof of Russian involvement is “fantasy politics.” However, the Macron government did later indicate that it believes the British claims of Russian involvement. In the U.K., Labour leader Corbyn refused to endorse May’s claim of Russian responsibility, reminding British voters what a “PM Corbyn” would look like. We don’t think diplomatic expulsions will make much difference and we don’t expect major sanctions to follow. Sadly, the lack of an effective response will only embolden Putin to take more aggressive steps.

Abe’s woes continue: The land scandal that has ensnared Finance Minister Aso is expanding. If Aso and perhaps Abe either ordered or knew documents were altered, it could bring down his government. The end of Abe would likely end Abenomics as well. We would expect a “knee-jerk” rally in the JPY and a weaker Nikkei.

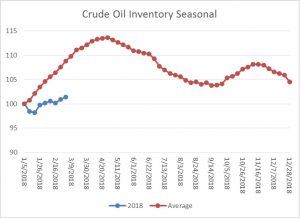

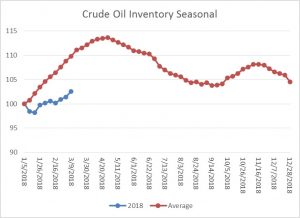

Energy recap: U.S. crude oil inventories rose 5.0 mb compared to market expectations of a 1.9 mb build.

This chart shows current crude oil inventories, both over the long term and the last decade. We have added the estimated level of lease stocks to maintain the consistency of the data. As the chart shows, inventories remain historically high but have declined significantly since last March. We would consider the overhang closed if stocks fall under 400 mb.

As the seasonal chart below shows, inventories are usually rising this time of year. This week’s rise was more in line with a normal increase in oil inventories during late winter into spring. If this pattern continues, oil prices may come under further pressure in the short run, although it still appears to us that prices are undervalued.

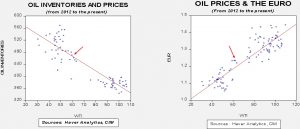

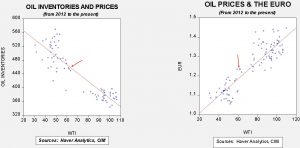

Based on inventories alone, oil prices are undervalued with the fair value price of $63.90. Meanwhile, the EUR/WTI model generates a fair value of $75.13. Together (which is a more sound methodology), fair value is $71.45, meaning that current prices are below fair value. Oil prices have been struggling on fears that U.S. production is going to overwhelm OPEC supply cuts. Earlier this week, we published our Quarterly Energy Comment[2] looking at the rapid rise in production without a commensurate increase in rig counts. We wonder if that production level can be maintained without an increase in resources. If not, oil prices should move higher once seasonal pressures dissipate.

[1] https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2018/03/trump-swinging-the-axe-at-tillerson-mcmaster-sessions-jared-and-ivanka

[2] See Quarterly Energy Comment, 3/13/18