by Bill O’Grady and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] Happy Monday! It’s the last day of April (which felt more like early March temperature-wise). Here is what we are watching today:

Trade week: There is a lot of trade action scheduled this week. First, the trade delegation is in China this week. Treasury Secretary Mnuchin, NEC Director Kudlow, USTR Lighthizer and NTC Navarro will discuss trade with Chinese negotiators. This team is divided; the first two tend to support free trade, while the latter two usually want trade impediments. It’s not clear if much will come of these negotiations. Since they don’t face a deadline, we would be surprised by a breakthrough. China will likely try to divide the group, which would appear to be an easy task. It is interesting to note that Lighthizer didn’t want this trip now.[1] He wanted to focus on other trade negotiations. This brings us to the second trade event this week, the steel tariff exemptions, which are expected tomorrow. Commerce Secretary Ross told Bloomberg that not all nations will get an extension of tariff relief.[2] Currently, Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, the European Union, Mexico and South Korea were granted temporary tariff exemptions. South Korea is the only nation on this list that has been granted permanent relief due to its agreement on steel and car imports. The EU has indicated it will retaliate if steel and aluminum tariffs are applied to the group. Third, NAFTA negotiations were expected to wrap up this week but it doesn’t appear that will happen, in part, because Lighthizer is in China. We still expect a deal with NAFTA to be completed soon.

May trouble: PM May has seen her inner circle move to a harder stance on Brexit after her home secretary, Amber Rudd, stepped down and was replaced by Sajid Javid. Rudd was involved in the Windrush scandal, where the descendants of Caribbean immigrants from Commonwealth nations, originally brought to the U.K. in the 1960s, were subjected to deportation due to their lack of clear documentation. Rudd misled Parliament on the scale and scope of the deportations. Rudd was a “soft Brexit” supporter, who leaned toward joining the EU customs union. Javid is considered a hard liner on the issue. The shift has contributed to recent GBP weakness.

Iran nuclear deal: There is growing speculation that the Trump administration will likely pull out of the Iran nuclear deal. President Trump has been a frequent critic of the deal, calling it “the worst deal ever” because it allows Iran to install more centrifuges after 10 years at its Natanz facility as well as enrich uranium at its Fordo facility in 15 years. In addition, new Secretary of State Mike Pompeo expressed over the weekend a distrust for Iran, describing its activities in the Middle East as “destabilizing.” EU leaders are trying to keep the deal together; if the U.S. does end the pact, it isn’t clear whether Europe will cooperate on sanctions. And, it is almost certain that China will not.

A looming threat: President Trump has indicated he will shut down the government in September if Congress doesn’t give him more funding for his Mexican border wall. Although it’s too early for the financial markets to care, by mid-summer this could become an issue, especially so close to the midterms. Historically, such turmoil in front of elections hurts the instigating party but this time around we are not so sure it would be all that harmful to the GOP. The upcoming elections will be “base v. base” and actions that enthuse base voters may be more important than wooing independents. A case in point:

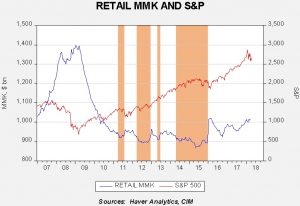

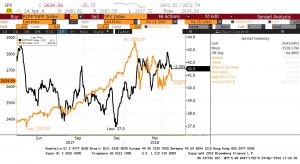

This is a chart we ran last week that shows the S&P 500 along with Trump’s approval rating. The low in his approval rating came around the time the tax bill passed. Note that the president’s approval rating has improved as the administration has shifted toward trade impediments. The congressional GOP wants to run on the tax cut; this data suggests that such a plan probably won’t work because the right-wing populists were not impressed with that bill because most of the benefits go to the right-(and left-)wing establishment. On the other hand, “going to the mattresses” on the border wall will likely energize the right-wing populists. Although President Trump’s negotiating style is to stake out an extreme position and then move to a more conciliatory agreement, the secret of his success is that he has no problem with watching the other party become uncomfortable in negotiations. [3] Thus, the chances of brinkmanship and shutdown threats could become quite rampant by late summer.

[1] https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-plans-trade-offers-for-u-s-envoys-on-high-stakes-trip-1525029506

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-29/ross-says-u-s-to-extend-duty-relief-to-some-allies-but-not-all

[3] https://www.axios.com/one-trick-pony-inside-trumps-negotiating-style-3b60acf3-76e1-4c7d-9c6b-8792ad38479b.html