by Bill O’Grady and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] Happy Monday! We are seeing a bit of optimism this morning as Chinese equities rallied overnight. There was nothing in the news that was necessarily bullish for China but a constant drumbeat of supportive statements from CPC officials has likely given investors the idea that the government will directly support the economy and perhaps the equity market. Here are the other items we are watching this morning:

The INF Treaty: It appears the U.S. is preparing to end its participation in the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty, a late-Cold War agreement that limited short- and intermediate-range nuclear weapons from the European theater.[1] There is evidence to suggest Russia has been violating the treaty for some time; Russia makes similar accusations against the U.S. Although the demise of this treaty is worrisome, it was really a relic of America’s unipolar movement. The INF puts the U.S. at a significant disadvantage to China in the Far East and would have needed to be scrapped at some point. But, what this action likely shows more than anything is that the world is again devolving into competing blocs and is additional evidence that the post-Cold War world is moving from American dominance to a more unstable geopolitical situation. If this view is correct we will likely see more modifications in other arrangements over time.

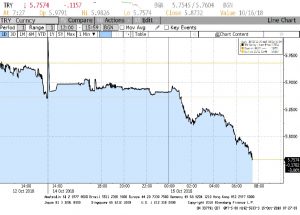

The Khashoggi affair: The Saudi Royal family is working hard to contain the uproar over the death of Jamal Khashoggi, a prominent Saudi journalist. The current narrative around his death, which took a while for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) to admit had occurred, is that it was an arrest gone awry. Obviously, there are massive problems with this story. First, the crown prince projects the image of being in full control. For this incident to have been a blunder undermines this image. Second, Turkey appears to have a significant degree of signals intelligence on what happened inside the Saudi consulate. And, President Erdogan has played his hand deftly, leaking information on a selective basis to undermine any story coming from Washington or Riyadh. Ankara is working to extract as much as it can with the information it has. Erdogan’s goals would be to extend Turkey’s power projection into the Persian Gulf[2] and to reduce Kurdish influence in northern Iraq and Syria.

Our key takeaway from this event is that the U.S. isn’t going to rupture its relations with the KSA over this affair because the Saudis are simply too important to isolating Iran and maintaining some degree of order in the oil markets. But, it is also becoming clear that the crown prince is a significant danger to regional stability. The list of his rash actions is long.[3] Although some members of the Trump administration are clearly fond of Mohammad bin Salman (MbS), he is proving to be a dangerous actor. Thus, we wouldn’t be surprised to see at least some steps to curtail his power; the history of the KSA shows that kings can be removed and crown princes replaced.[4] If MbS survives this affair with no changes in power, it would suggest he has solidified his control and will be the fount of continued turmoil.

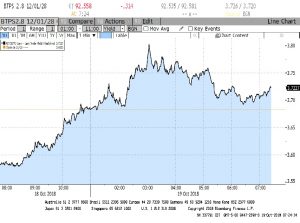

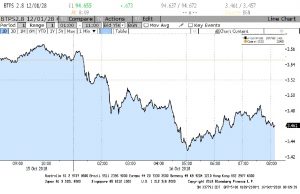

Italian chicken: Tensions between the European Commission and Italy remain elevated. On Friday, Moody’s downgraded Italian local and foreign currency sovereign debt to Baa3 from Baa2,[5] putting its debt near “junk” status. Although some commentators are arguing that this morning’s equity rally is partly due to “relief” that Moody’s didn’t take Italy to junk status, this appears to us to be a stretch. For the most part, the action taken by Moody’s was about as expected. S&P is scheduled to review Italy’s debt on Friday. The EC continues to express displeasure with Italy’s budget and the Italian government continues to indicate that it intends to keep its budget regardless of the EC’s protests.

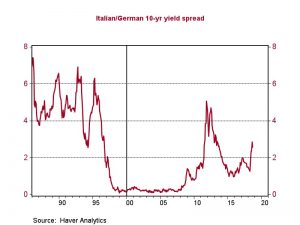

The Italian position is actually rather simple. Although there is occasional talk of Italy leaving the Eurozone, polls suggest that Italians actually favor being in the single currency.[6] The current government has made it clear that it has no plans to exit the Eurozone.[7] Given how high Italian interest rates were pre-Eurozone, it is understandable why being part of the single currency is popular.

The euro started in 2000, as shown by the vertical line on the chart, but note that yields between Germany and Italy converged in the late 1990s in anticipation of Italy joining the Eurozone. Even in the worst of the Eurozone crisis in 2011-12, Italy’s yield spread with Germany didn’t reach the pre-euro peaks. The chart also makes it obvious why a spread of 4% is psychologically important.

Italy wants to stay inside the Eurozone but to ignore the fiscal restraining rules. Although Italy has enjoyed lower interest rates, its economic growth has been stagnant.

This chart shows Italy’s industrial production. We have placed a vertical line showing the start of the Eurozone. Note that production growth has been nil since entering the single currency.

The populist government has a mandate to (a) boost growth, and (b) keep interest rates low, which likely means staying in the Eurozone. The EC does not want to see a large Eurozone economy flagrantly defy the fiscal rules. These are incompatible goals. Thus, we have a classic game of “chicken.” We don’t expect Italy to blink here. The enforcer of fiscal rules in the EC is Germany and Chancellor Merkel’s political situation has deteriorated enough to likely prevent a strong response from the Merkel government. If Italy is allowed to violate the fiscal rules, at least initially, it’s bearish for the EUR. However, if we end up with a wider easing of fiscal rules that leads to tighter monetary policy, we could see the EUR eventually strengthen.

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/bolton-pushes-trump-administration-to-withdraw-from-landmark-arms-treaty/2018/10/19/f0bb8531-e7ce-4a34-b7ba-558f8b068dc5_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.4d4ffd595242

[2] https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2018/10/turkey-gulf-rapprochement-with-kuwait-may-cause-tension.html

[3] For example, see: Weekly Geopolitical Reports, Moving Fast and Breaking Things: Mohammad bin Salman, Part I (11/20/17); Part II (12/4/17) and Part III (12/11/17).

[4] See Weekly Geopolitical Report, Saudi Succession (1/20/15).

[5] https://www.ft.com/content/848c8f7e-d3e1-11e8-a9f2-7574db66bcd5

[6] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-italy-euro-poll/polls-show-most-italians-want-to-stay-in-euro-idUSKCN1IW0MT

[7] https://www.ft.com/content/9b324788-d4b2-11e8-ab8e-6be0dcf18713