Tag: stocks

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Meet Sanae Takaichi (November 10, 2025)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

In October 2025, Japan made history by electing its first female prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, a staunch conservative and protégé of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Her rise to power marks a significant shift in Japan’s political landscape, with implications for foreign affairs, domestic policy, and financial markets. As we show in this report, Takaichi’s administration promises a blend of hawkish national security, aggressive fiscal expansion, and economic revitalization, all underpinned by a nationalist ideology. As always, we wrap up the report with a discussion of the investment implications of her rise to power.

Note: The accompanying podcast for this report will be delayed until later this week.

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – The Cap-Weighted and Equal-Weighted S&P 500 (September 8, 2025)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

There are many ways to describe the strong performance in large cap US stock prices this year. You could simply call it a bull market, with the S&P 500 total return index up 31.2% since its low in early April and up 11.5% year-to-date. The strong buying pressure could even be called a “euphoria.” With continued gains, it would be no surprise if some observers started referring to it as a return to the type of “irrational exuberance” seen in the 1990s. In any case, the market is exhibiting strong momentum, especially in the growthy sectors such as Information Technology and Communication Services. Indeed, investors now widely understand that the lion’s share of the uptrend this year has come from just a few stocks within those sectors, i.e., the Magnificent 7. A key question is whether these trends will continue. And to the extent that there is a risk of these trends reversing, is there a good way to hedge the associated downside risk?

The growth of index investing in recent decades is probably one reason for the outperformance of large cap growth stocks like the Mag 7. Many individual and institutional investors simply channel their US large cap stock investments into funds tracking the S&P 500 Index, where each holding is weighted by the stock’s total market capitalization. Funds channeled into this version of the S&P 500 go disproportionately to those stocks with big market caps, especially the Mag 7, helping them appreciate even more. But there is also a version of the S&P 500 in which the allocation to each stock is an equal 0.2% — the S&P 500 Equal Weight Index. In this methodology, stocks with smaller capitalizations and more “value” characteristics have a higher representation than they do in the capitalization-weighted version. If we compare the performance of the cap-weighted S&P 500 to that of its equal-weighted counterpart, we can get a sense of the relative advantages or disadvantages of each index during different market scenarios.

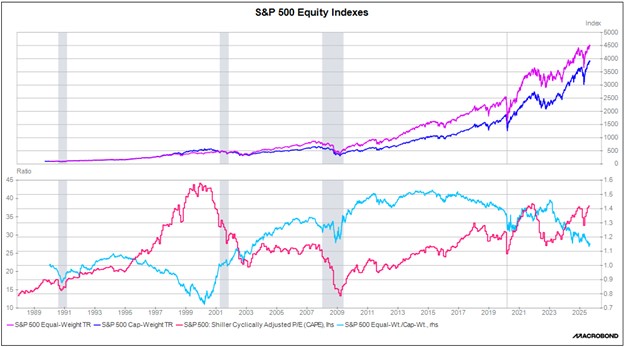

In the upper panel of the following chart, we show the S&P 500’s total return index in both its cap-weighted and equal-weighted forms, with each based to 100 in January 1990. The figure shows that over the last 35 years, the equal-weighted variation of the S&P 500 has produced a meaningfully higher total return than the market cap-weighted one. (Consistent with finance theory, the higher return for the equal-weighted index also comes with a higher standard deviation.)

Importantly, the relative performance of the two indexes changes over time. In the bottom panel of the chart, the light blue line shows the relative performance of the equal-weighted index to that of the version weighted by market cap. We have also included the Case-Shiller cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio as a measure of average stock valuation.

In the bottom panel, the long downtrends in the blue line from 1995 to 2000 and from 2015 to the present coincide with periods of intense market enthusiasm, strong momentum in big, popular growth stocks, and lagging performance in relatively smaller, less growthy stocks. These periods generally happen when investors are pouring funds into the market and driving up valuations. In these periods, including the present, it can be tempting for investors to just focus on the large cap growth stocks driving the market. However, the chart clearly shows that when market enthusiasm eventually reverses and investors pull out of the market, the relative advantage of the equal-weight index snaps back sharply. This reflects the sudden sell-off in trending, growthy, highly weighted stocks during such periods. In sum, the bottom panel illustrates how concentration risk increases in long, strong bull markets. This tends to set the stage for sharp portfolio declines when markets go into reverse, even for investors who think they are well diversified because they are invested in the cap-weighted S&P 500.

The lesson from this discussion is that while fast-rising large cap growth stocks like the Mag 7 may still have some momentum left, investors should also consider broad diversification with meaningful exposure to undervalued and overlooked stocks, which could have the potential for solid, longer-run returns.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #147 “The Cap-Weighted and Equal-Weighted S&P 500” (Posted 9/8/25)

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #145 “No Country for Recessions” (Posted 8/8/25)

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – No Country for Recessions (August 4, 2025)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

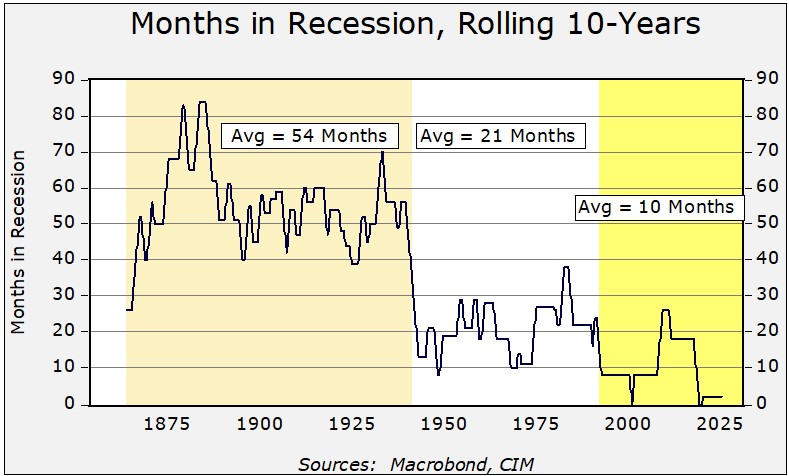

Recessions in the United States have become less frequent over time. To illustrate this, the chart below shows data from the National Bureau of Economic Research, the official arbiter of recessions in the US, which has been establishing business cycles since January 1854. In the chart, we show the total months spent in recession over a rolling 10-year period. Clearly, we have seen the incidence of recession decline over time. From 1864 until 1940, recessions occurred, on average, 54 months out of 120 months, or 45% of the time. From 1941 to 1991, the average declined to 21 months, or 18% of the time. Since 1991, the average fell to 10 months, or 8% of the time.

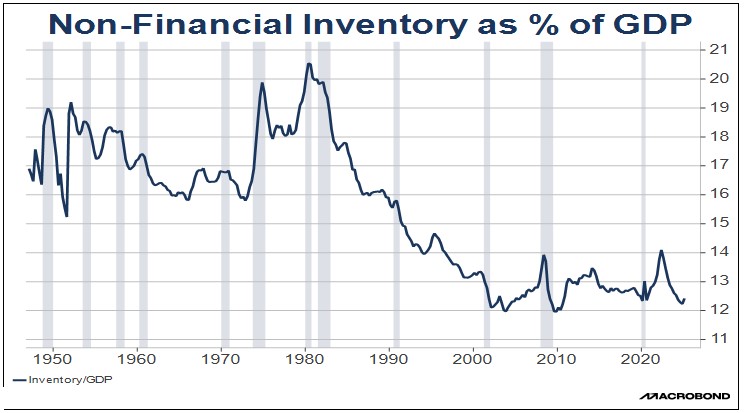

Why has the incidence of recessions declined? There are three primary reasons. First, as the economy evolved into being dominated by services instead of manufacturing, there were less inventory misallocations causing slumps, especially after 1980. As shown in the next chart, inventories relative to gross domestic product (GDP) have clearly fallen. Therefore, the likelihood of excess inventories or other issues arising from misallocation of inventory also fell.

Second, until the 1930s, recessions were thought to be natural occurrences. Often, the burden of policies that allowed recessions tended to fall on debtors and the lower classes, who had limited political influence. After WWI, this idea became contested and was one of the reasons for the unraveling of the gold standard. Because the gold standard created inelastic conditions for liquidity, central banks were restricted from easing credit conditions during downturns, leading to deflation. After WWII, monetary and fiscal policy became countercyclical; in other words, policies were designed to either prevent or mitigate recessions. By the mid-1990s, monetary policy transparency became the norm, further reducing the amount of policy shocks.

The third factor behind less-frequent recessions is the expansion of globalization that started in 1978 with deregulation and accelerated after the end of the Cold War. The rise of globalization increased the available supply, which led to lower inflation and a decline in interest rates. This period, dubbed “the great moderation,” made it easier to extend the business cycle.

This history raises two questions. First, will this period of infrequent recessions continue? And second, what are the ramifications if it does? Addressing them in order, it’s likely that infrequent recessions will continue because two of the three conditions described above should remain in place. We expect that services will continue to dominate the economy, while modern inventory management will maintain stability. At the same time, countercyclical policy isn’t likely to change. If anything, policy accommodation appears to be expanding (raising inflation concerns). In our view, only the third condition for less-frequent recessions will be less supportive. As the US attempts to rebalance the global trading environment, imports will become less plentiful, and the potential for supply shocks will rise. Of course, as domestic production responds, the potential for foreign-driven supply shocks (as observed during the pandemic) will also be less of an issue. But overall, the trend toward fewer downturns looks to be in place.

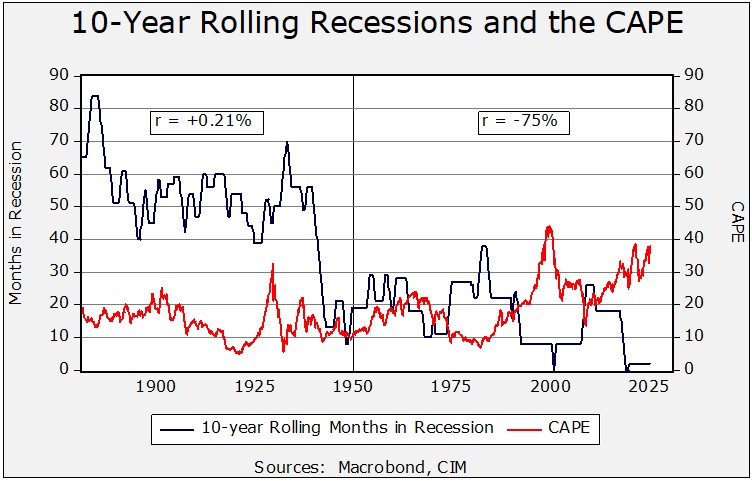

What does this mean for equity markets? Less frequent recessions, at least in the postwar period, correlate with higher price/earnings multiples. We show this in the chart below, which overlays the rolling decades of recessions with the Shiller cyclically adjusted P/E ratio. From 1870 to 1950, the correlation was low and positive. However, since 1950, the correlation has increased significantly and turned negative. In other words, the declining occurrence of recessions is now associated with higher stock valuations.

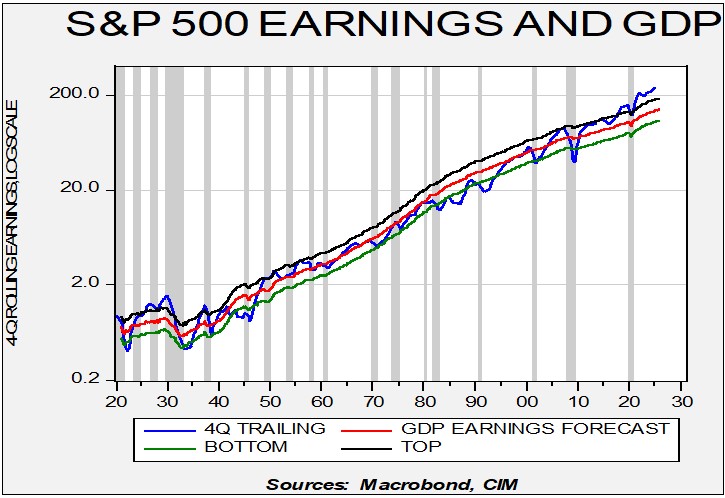

Finally, the chart below shows S&P 500 earnings on a four-quarter rolling basis compared to a regression of earnings to nominal GDP. Recessions are indicated by the vertical grey bands. The chart shows that, in the postwar era, recessions tend to depress earnings. Thus, if recessions remain less frequent, it makes sense that the earnings multiple would be higher. Investors generally can worry less about economic downturns, giving them greater confidence to bid up stock values relative to earnings.