Author: Rebekah Stovall

Asset Allocation Weekly (July 23, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

The availability of ample investment capital is vital for economic growth in both rich, well-developed countries and poorer developing nations. However, if the available capital is poorly utilized and/or debt levels get too high, the results can be quite negative. In such a situation, economic growth can slow as companies and individuals struggle to make their debt payments. Economic shocks can cause companies, individuals, or governments to miss their payments and go bankrupt, potentially sparking a financial crisis and damaging the country’s financial system. High debt levels in China have been especially concerning for years, so it may be useful to review the latest data on that country from the Bank for International Settlements.

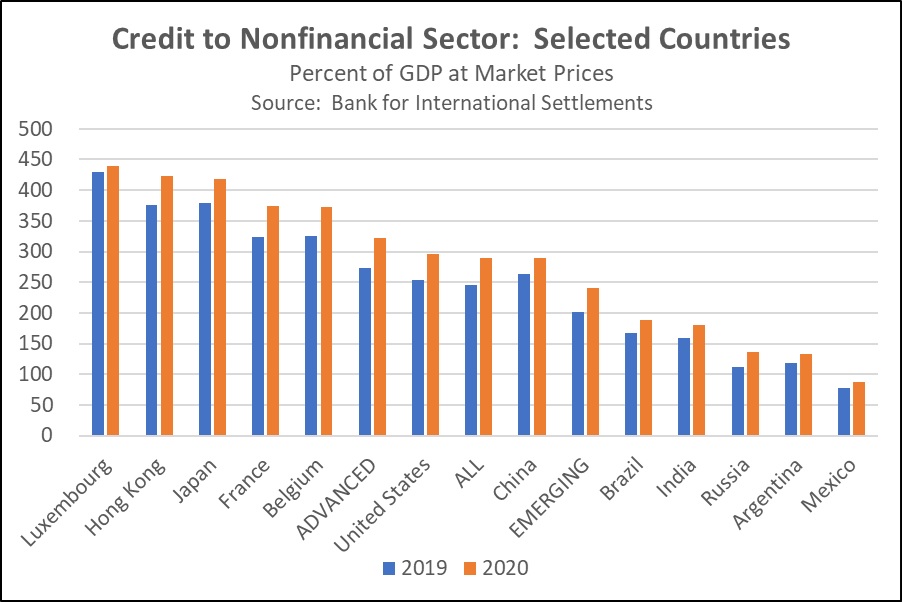

As shown in the following chart, the stronger, richer, advanced countries can typically tolerate a higher level of debt (per BIS practice, we focus on total credit to the nonfinancial sector). For the average advanced country in the BIS database, total credit to the nonfinancial sector stood at 321.3% of gross domestic product (GDP) at the end of 2020. For the average emerging market, credit to the nonfinancial sector stood at just 240.1% of GDP. Note, however, that China stands out with its debt burden of 289.5%, which is significantly higher than the emerging market average and far above the burdens for other large developing countries like Brazil, India, and Mexico.

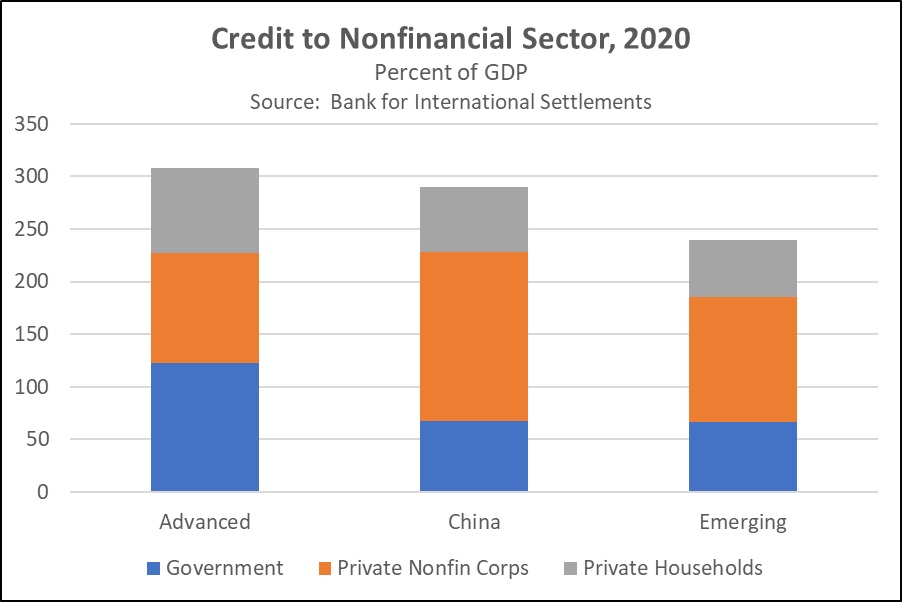

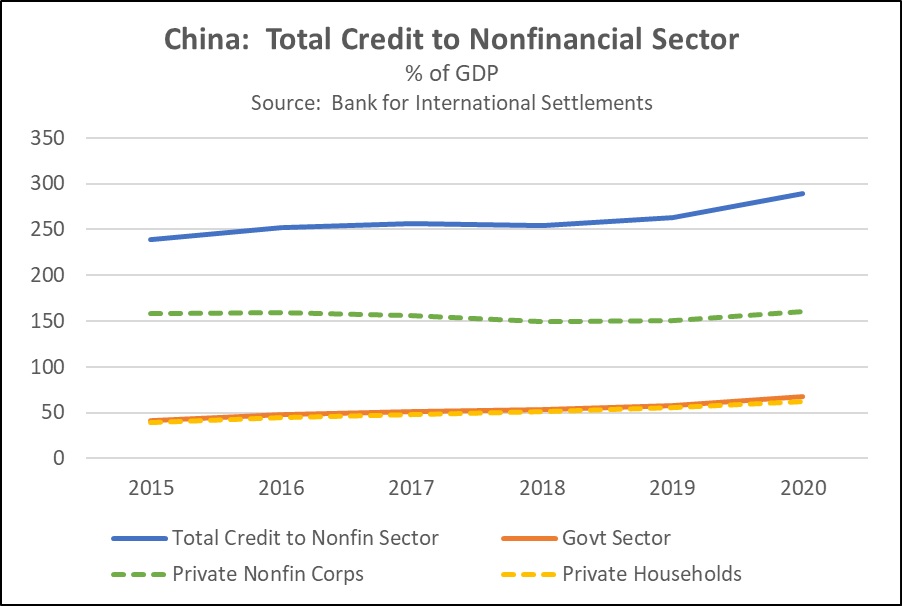

The BIS figures are broken down into the amount of credit provided to the nonfinancial corporate sector, the household sector, and the government sector. At this level of detail, we can see that China’s high overall debt burden stems mostly from its nonfinancial corporate sector. In China, nonfinancial corporate debt alone stands at 160.7% of GDP compared with 119.4% of GDP in the average emerging market. Moreover, China’s high corporate debt relative to the rest of the emerging markets has persisted for years. Often, China’s corporate debt burden by this measure is almost half again as high as for the average emerging market. China’s nonfinancial corporate debt burden is even higher compared with the 104.4% of GDP in the average advanced country. Indeed, nonfinancial corporate debt to GDP in China is even higher than in high-debt Japan, and it is almost as high as in Belgium.

This high reliance on corporate debt marks a new strategy for China. During the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, Beijing relied primarily on government fiscal spending and public borrowing to support the economy, but that left many government entities burdened with debt for years afterward. In contrast, Beijing’s approach to supporting the economy during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic was to channel funds through the business sector to keep workers in their jobs and maintain production to the extent possible. The resulting boost to debt in the corporate sector was even bigger than the increase in debt within the government sector, as shown in the chart below.

Because of the boost in credit to the corporate sector last year, Chinese companies may now be hobbled by their high debt levels, especially if interest rates rise or the worsening U.S.-China geopolitical rivalry further crimps Chinese trade flows. This is one reason why we have taken steps to limit our exposure to China in our asset allocation strategies. In our view, China’s combination of high corporate debt levels and increased regulatory risks related to potential capital flow restrictions should argue for below-benchmark weightings to the country.

Asset Allocation Quarterly (Third Quarter 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

- There is no recession within our forecast period. Monetary and fiscal stimulus should continue in the U.S. over our three-year forecast period, yet at a decreasing rate as the economy recovers.

- After a surge in inflation this year and into next year, resulting from the economic recovery following the pandemic, inflation should settle within the Fed’s threshold.

- The ECB remains aggressively accommodative and is supported by the EU’s fiscal stimulus, which should help to hasten the pace of their economic recovery.

- Equity allocations among all strategies remain elevated with the retention of a heavy tilt toward value and, where risk appropriate, an overweight to small capitalization stocks.

- The high allocation to international stocks remains intact given our expectations of overseas growth.

- In the more risk-tolerant strategies where emerging market exposure is employed, mainland Chinese stocks are either vastly underweighted or excluded.

- Commodity exposure is retained with heavier concentration in the more risk-averse strategies for the advantages they afford during heightened geopolitical risk.

ECONOMIC VIEWPOINTS

Although the boundless fiscal and monetary spigots are unlikely to remain open indefinitely, we find there is ample liquidity and activity to propel the economic recovery through our three-year forecast period, albeit in fits and starts. Though we note that the prospect for a shortened business cycle exists, this is not our base case. Rather, we expect real GDP growth over the next three years, yet certainly at a less robust pace than we have experienced thus far this year.

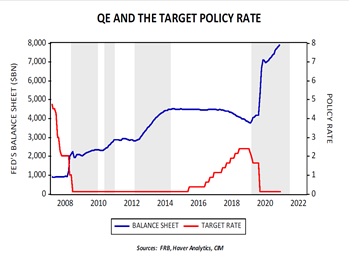

The latest meeting of the Fed registered growing concerns about persistently dovish policy. Where Fed members stated earlier in the year that they were “not even thinking about thinking about raising rates,” one of the ‘thinkings’ in the quote is now absent. The rise in core CPI that occurred in June, representing the largest monthly year-on-year increase in 30 years, has weighed upon the resolve of several Fed bank presidents. Nonetheless, though some have waivered on the prospect of being excessively accommodative for an extended period, we expect that the price increases measured against last year’s COVID-induced low base level and further pressure from rolling supply constraints will not prove durable. The higher probability is that current price increases will endure to varying degrees depending on products, but persistent increases beyond these supply adjustments are less likely. We expect that the Fed Chair and the composition of voting members will retain a dovish overall stance, despite some near-term cautionary flags being waved. The least likely Fed action is a decrease in the size of its balance sheet while simultaneously implementing a series of increases in the fed funds rate, as performed in 2018 and 2019. More likely is a decrease in the aggressive $120 billion monthly balance sheet purchases of Treasuries and mortgages. While this will probably lead to volatility in bonds and equities over a short period, similar to the “Taper Tantrum” of eight years ago, we expect prices to adapt relatively quickly.

In contrast with some Fed bank presidents expressing caution regarding future inflation, the European Central Bank [ECB] has pivoted significantly from its former position of combating inflation. Where it was previously unimaginable for the ECB to accept inflation above 2%, it is now willing to allow prices to run in excess of its ceiling. President Lagarde disclosed the ECB’s new policy framework of “symmetric 2% over the medium term” and the bank is expected to refresh its guidance on both policy rates and QE program. In addition, the sequential issuance of NextGenerationEU bonds as part of the COVID relief package will provide fiscal stimulus for the continent and support the euro as a reserve currency. Finally, the EU’s €1.1 trillion multi-year budget through 2027 has designated nearly half for modernization, adding further fiscal stimulus.

Beyond the U.S. and the EU, monetary and fiscal stimulus is rampant in developed nations as well as most emerging market economies as they attempt to recover from pandemic-induced recessions. Consequently, the world remains awash in liquidity. While this can lead to distortions in some asset prices and misallocations of capital, the liquidity will allow firms to remain viable during the recovery. The overriding issue, therefore, is whether the eventual reduction in the uber-accommodative postures will lead to a stunting of the business cycle or allow the global economy to enter an expansion. While we expect the latter to prevail, we note the potential for the former is greater than zero yet less likely within our three-year forecast period.

STOCK MARKET OUTLOOK

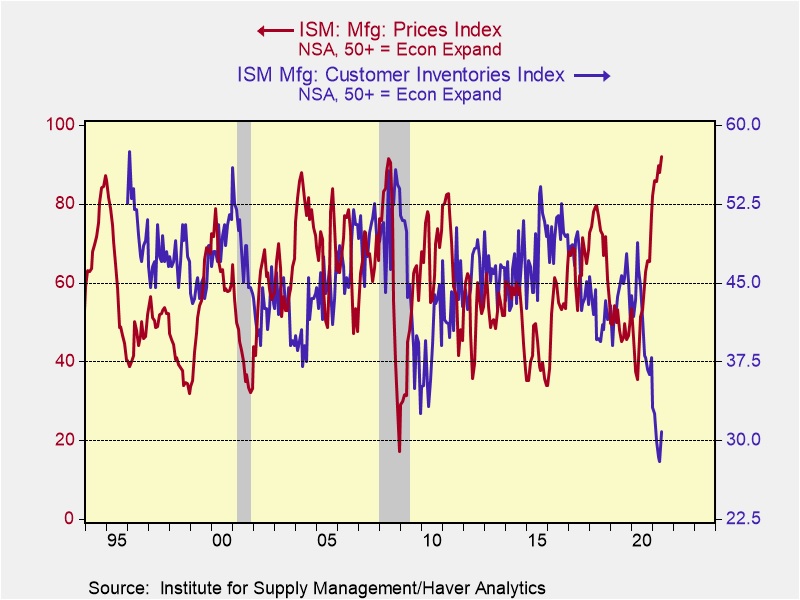

Exposure to equities remains intact as fiscal and monetary policies along with measures of sentiment all support continued economic recovery. Though our expectations have been tempered, our outlook remains positive despite near-term issues. One of the most cited issues is the supply shocks in different segments of the economy, whether semiconductors, building supplies, transportation, or used cars, among other items. The pre-pandemic trend of building redundant supply chains has accelerated and encouraged inventory accumulation, creating bottlenecks in supply and leading to rapid price pressures. The June CPI print of +4.5% year-over-year ex-food and energy underscores the price pressures from supply constraints as inventories are increased. As the chart shows, and economic logic dictates, building inventories historically leads to higher prices. The pandemic has magnified this effect to unprecedented levels, resulting in price increases, which we project could continue into early next year. However, as the uneven emergence from the pandemic unfurls and consumer appetites become satiated, price increases for certain goods could hold at higher levels but we don’t believe they’ll continue their ascent. Thus, we do not expect persistent rapid inflation.

Although the threat of inflation sends shivers through the equity markets, the economic recovery and potential move into expansionary territory bodes well for stocks. While inflation can negatively affect stocks in general, as future earnings are discounted at higher rates and P/Es compress, it affects companies, industries, and sectors disproportionately. Cyclical companies have historically held pricing power during periods of inflation, assuring continued profitability. Further, smaller entities are able to nimbly adjust to changes in supply chains and prices. Our original tilt to value versus growth, overweights to Industrials and Materials in U.S. large cap stocks, and lean toward lower capitalization companies were applied due to expectations of an economic recovery, but issues with near-term inflation don’t invalidate this premise. Rather, it underscores the benefits of this positioning as well as the overweights to Financials initiated in January and homebuilders in October 2020.

International developed markets are facing similar supply issues as the U.S., yet the ECB is more inclined than the Fed to allow inflation to run ahead of its target. We still consider the EU and U.K. to be lagging the U.S. economy by as much as half a year as they continue to struggle to emerge from the pandemic. Other developed nations (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Japan) are also lagging the U.S. in their respective economies, and their central banks, with the exception of New Zealand, remain ultra-accommodative. The strategies’ exposure to developed markets remains elevated and has an inherent overweight to the Materials, Industrials, and Financials sectors along with a decided tilt toward value, which mirrors the overweights in the U.S. portion. Regarding emerging markets, relative valuations are still attractive, encouraging the retention of a sizable weight to this asset class in the more risk-tolerant strategies. However, concerns surrounding Chinese equities are mounting as belligerence between U.S. and Chinese authorities continues. Since Chinese stocks account for upwards of 40% of the more popular emerging market indices, we find it more prudent to employ an ETF that excludes mainland Chinese stocks.

BOND MARKET OUTLOOK

At the end of last quarter, the bond market rallied on the heels of concerns voiced by several Fed members on their expectations of combatting future inflation. The yield on the long end of the Treasury curve compressed from 2.34% in April to 2.06% by quarter’s end. The curve flattened but remained positively sloped. In addition, the spread on corporate bonds continued to narrow, reflecting investor willingness to accept credit risk. As noted in our Stock Market Outlook, though equity investors have become wary of inflation, the bond market has generally sloughed these concerns. Although we maintain the view that high levels of reported inflation will only last through this year, our outlook for bonds over the forecast period cannot be construed as being particularly sanguine. Not only has the utility of long bonds been eroded due to the rally, but the potential pressure on yields accruing from economic growth moving from a recovery into potential expansion yokes our total return expectations for bonds, especially beyond the seven-year maturity range. Accordingly, the strategies with income as a component have reigned in duration dramatically this quarter and carry heavier weightings to Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities [MBS]. While MBS carry both extension risk and also risk if the Fed unwinds some of its MBS positioning on its balance sheet, we view these as being compensated by the spreads widening close to historic levels.

OTHER MARKETS

Since S&P separated REITs into its own GICS sector in 2016, the complexion of REITs has become more varied. Retail, office, and hospitality now only account for roughly one-fifth of the market, while warehouses, data centers, and cell towers represent the majority. We view these latter segments as being fully valued and the traditional segments priced for recovery, thus our consensus expectation over the forecast period is for REITs to earn their dividend with little to no capital appreciation. As a result, REITs are employed solely in the Income strategy for the varied source of income they provide. Similarly, speculative grade bonds appear fully valued given their continued compression of option-adjusted spreads over the past year. Consequently, total return expectations for spec bonds are muted and they are used only in the Income strategy.

Expectations for continued global recovery lead to the retention of a broad basket of commodities containing a majority weight to energy components as well as industrial metals. In the more risk-averse strategies, this position is used in conjunction with exposure to gold, which we find attractive as the prospect for geopolitical risk remains elevated. In the more risk-seeking strategies, we added a position in silver for its industrial uses during a global economic recovery.

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Nigeria’s Conflict with Biafra and Social Media (July 19, 2021)

by Thomas Wash | PDF

On June 2, Twitter (TWTR, $61.72) removed a tweet posted by Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari that vaguely threatened Biafran separatists. Buhari’s tweet appeared to be in response to a series of attacks against Nigerian security forces and police officers. In any case, Buhari has become the latest high-level political leader to have his tweet removed by Twitter. The move comes just months after former U.S. President Donald Trump was permanently banned from the platform. In this article, we explore Nigeria’s current problems in Biafra and the government’s response. We also show how the situation reflects the growing friction between social media companies and governments all over the world. We end with a discussion of the ramifications for investors.

Daily Comment (July 16, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] | PDF

Good morning, all! U.S. equities appear to be headed for a higher open this morning. The overnight news was rather quiet. Our report begins with international news and discussions about rising tensions between Poland and the EU, Iranian hackers targeting workers in the defense industry, and the flood in western Europe. U.S. economics and policy news are up next, including an update on the protests in Cuba and the infrastructure bill. China news follows, and we end with our pandemic coverage.

International news: Flood in western Europe, defense workers being targeted by Iranian hackers, and rising tensions between the EU and Poland.

- African nations are planning to lower intercontinental tariffs and are looking to raise $8 billion to offset the loss of tariff revenue. The decision is designed to make intra-trade within Africa relatively easier.

- On Thursday, a flood in Germany and Belgium caused by record rainfall across western Europe led to 100 confirmed deaths and more than 1,000 people feared missing.

- A secretive Israeli spyware company, Candiru, sold its software exclusively to governments. The software makes it easy for states to hack into iPhones, Androids, Macs, PCs, and cloud accounts. It has been used by governments to monitor and track dissidents.

- Poland and the European Union continued their six-year feud over the rule of law. On Thursday, the European Court of Justice ruled that Poland’s system of overseeing and disciplining judges is not compatible with EU law. In response, Poland has argued that the ruling goes against the Polish constitution. If Poland persists with its oversight system, the commission could ask the court to impose daily fines.

- Russia banned an investigative website that published a report suggesting that President Vladimir Putin secretly fathered a child outside of his marriage. The publisher of the report, Proekt Media, is based in the U.S.; however, anyone associated with the site potentially faces a prison sentence.

- Facebook (FB, $344.46) announced that it removed several accounts connected to a group of Iranian hackers that targeted employees of defense and aerospace industries in the U.S. and Europe.

- The European Central Bank is expected to maintain its policy accommodation for the foreseeable future, according to a Bloomberg survey of economists.

Economics and policy: U.S. issues warning about business in Hong Kong, a U.S. tech firm is in talks to purchase its own foundry, and the Biden administration is exploring ways to restore the internet in Cuba.

- Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell reasserted his belief that inflation is likely going to be transitory. Although he has expressed concern with the rise in inflation, he stated it would be a mistake to withdraw the stimulus prematurely.

- The Biden administration restored protection of the Tongass Forest by re-imposing a ban on logging, roads, and mining in undeveloped forests.

- The Biden administration plans to issue a formal warning to companies doing business in Hong Kong. Officials are concerned that companies are not taking risks posed by China’s takeover of the region seriously enough.

- Intel (INTC, $55.81) is exploring a deal to purchase GlobalFoundries Inc. from Mubadala Investment, an investment arm of the Abu Dhabi government. Intel is expected to bid $20 billion for the U.S.-based foundry.

- The U.S. is exploring ways to help restore internet access in Cuba. The Cuban government shut off the internet following protests over its handling of the pandemic. Washington is also ready to send vaccines as long as the shots are administered by an international organization.

- Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has scheduled a vote on the infrastructure bill to take place on Wednesday. The bill is still largely unwritten and there have been a few obstacles that might prevent the bill from becoming law. Currently, the two sides are debating changes to funding mechanisms and the bill’s spending priorities.

- The U.S. is weighing a digital trade agreement to counter China’s growing influence. The new agreement will attempt to establish a global standard to the digital economy and will look to bring in countries from the TPP agreement.

China: Beijing gives exemption for firms listing in Hong Kong, China is growing uneasy about U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, and pork prices fall in China.

- Chinese officials announced that firms going public in Hong Kong will be exempt from first seeking approval from the country’s cybersecurity regulator. Regulators will still vet companies that are looking to go public to make sure they are complying with local laws, but only those that plan to list in other countries will undergo a formal review.

- China has expressed concerns about the quick U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. There are growing fears within Beijing that instability from Afghanistan, with which it shares a small 46-mile border, could spread into its country. Over the last few years there has been growing anti-China sentiment due to the country’s growing influence in the region and its treatment of Uighur Muslims. On Wednesday, an explosion near a bus carrying Chinese workers was described by Beijing as a terrorist attack.

- China refused to set up a meeting with Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman and her Chinese counterpart, Le Yucheng. Instead, China offered Sherman a meeting with Xie Feng, who is three ranks below Yucheng. The move was widely viewed as a snub and will likely heighten tensions between the U.S. and China.

- Chinese pork imports are expected to drop 50% following a sharp decline in domestic pork prices.

- Xi and Biden are expected to meet with other world leaders at the virtual APEC meeting on Friday. The informal meeting will focus on ending the pandemic and efforts to support the global recovery.

- At the urgency of the World Health Organization, Beijing is mulling over whether it will allow another inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus.

COVID-19: The number of reported cases is 189,024,605 with 4,068,772 fatalities. In the U.S., there are 33,977,713 confirmed cases with 608,406 deaths. For illustration purposes, the FT has created an interactive chart that allows one to compare cases across nations using similar scaling metrics. The FT has also issued an economic tracker that looks across countries with high-frequency data on various factors. The CDC reports that 388,738,495 doses of the vaccine have been distributed with 336,054,953 doses injected. The number receiving at least one dose is 185,135,757, while the number of second doses, which would grant the highest level of immunity, is 160,408,538. The FT has a page on global vaccine distribution.

- The U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy expressed concerns over the growing wave of misinformation about COVID-19 and related vaccines. He has called on tech companies to adjust their algorithms to demote false information.

- Health officials in southwest Missouri have asked for emergency hospitals to be set up to deal with the surge in cases of the Delta variant.

- Los Angeles County has told its residents that it must wear masks indoors following a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases. The county is weighing implementing new restrictions if cases continue to rise.

- President Biden announced that he is considering lifting travel restrictions with Europe following his meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

- Half of the people that contract COVID-19 experience other health complications. Although complications were more common for those over 50, young adults have also experienced health issues.

- Canada announced that it may start allowing vaccinated travelers to enter the country in September if “the current positive path of vaccination rates and public health conditions continue.”

- A Hong Kong study shows that health workers who have been fully vaccinated with the BioNTech/Pfizer (PFE, $40.09) shot have 10 times the mRNA than those who were vaccinated with the Sinovac Biotech (SVA, $1.36) shot.

- Nursing homes have struggled to convince staff to get vaccinated. Slightly more than half of nursing home staff have been fully vaccinated.

- States are starting to outlaw the required use of masks and proof of vaccinations in school.

Asset Allocation Weekly – #45 (Posted 7/16/21)

Asset Allocation Weekly (July 16, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

The pandemic-related expanded benefits for the unemployed are expected to end in September. States that have ended the booster early have seen a sharper decline in initial claims than states that haven’t ended them. Although the end of enhanced employment benefits could help resolve the labor shortage, there is also the likelihood that it could lead to an increase in the unemployment rate. If this happens, this could force the Fed to rethink its decision regarding when to reduce its policy accommodation. In this report, we will discuss the possibility that the unemployment rate could rise and how it could impact monetary policy.

Currently, the labor market appears to be improving. National continuing jobless claims have fallen from an all-time high of 23 million in March 2020 to 3.5 million in June 2021. Additionally, during this time frame, the unemployment rate fell from 14.8% to 5.9%. The labor market has tightened so quickly over the last few months that firms have struggled to find workers to fill their open positions. However, this labor tightness is somewhat misleading. Continuing claims, currently at 3.3 million, remain well above the historical average of 2.8 million. In addition, employment has not recovered to its pre-pandemic peak. Finally, labor shortages remain especially bad in particular industries, most notably, Leisure and Hospitality and Transportation and Warehousing.

Since the start of 2020, many firms have been forced to limit their operating capacity to meet COVID-19 restriction guidelines. Firms, particularly in services, were forced to reduce the number of customers they could serve, limit their offerings, and, in some cases, temporarily shut down to comply with restrictions. As a result, there was a huge drop-off in hiring in the services sector at the start of the pandemic. Although the removal of restrictions led to a resurgence in hiring, the recovery was uneven.

As the recovery accelerated, firms began to rapidly increase hiring. Services related to tourism and travel, in particular, saw a spike in sales. Consumer expenditures on travel and airlines have doubled from the prior year. As a result, firms that found themselves understaffed began raising wages. When that didn’t work, states voluntarily withdrew from the extended unemployment benefits program to increase the size of the available workforce. Although somewhat successful, the initiative highlights the fact that there are still a lot of workers that haven’t committed to looking for work. Hence, when extended benefits end in September, it could lead to an increase in the number of unemployed people genuinely looking for work.

Although benefits recipients are technically required to look for work, some states have been lenient on enforcing it. Therefore, the end of extended benefits could lead to an increase in the civilian labor force, thus pushing up the unemployment rate. This is because the unemployment rate is calculated as a ratio of unemployed persons to the civilian labor force. The civilian labor force is defined as those working plus those who are unemployed but actively seeking employment. If those who are relying on the expanded benefits decide to join the labor force, ending expanded benefits may expand the labor force and usual frictional labor market issues may, at least temporarily, lead to a rise in the unemployment rate.

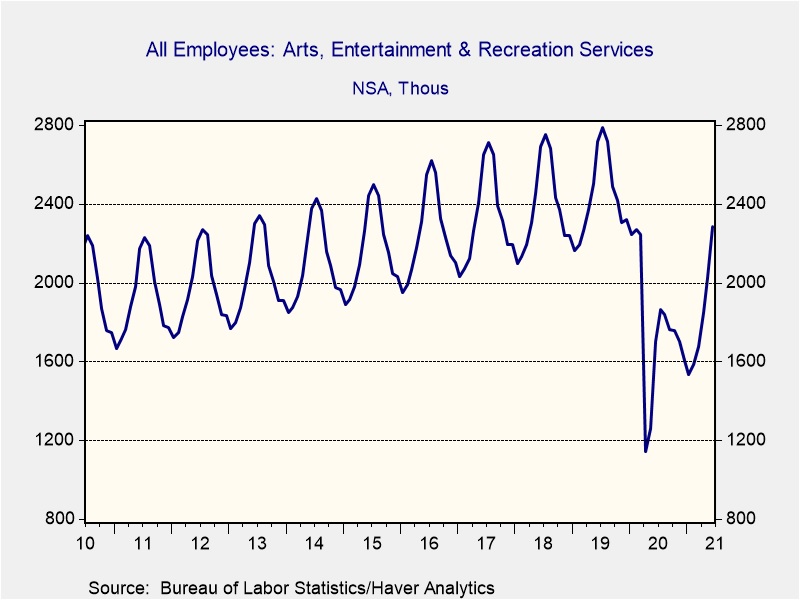

The timing of the expiration of the expanded benefits may also play a role. Many of the new jobs that have been added over the last five months have come from industries that are traditionally seasonal. For example, leisure and hospitality accounted for 60% of the jobs created in that period. For comparison purposes, the sector has accounted for 20% of the jobs created in the last decade. This problem becomes more apparent when you consider that a growing share of Leisure and Hospitality jobs are coming from Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation, a sector known for its seasonal swings. In other words, ending the expanded benefits could lead people back into the labor market at a time when firms are starting to slow their hiring.

In response to the June jobs report, St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard suggested that the labor market may be tighter than it looks. Given Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s focus on full employment in guiding monetary policy, Bullard’s comments were regarded as rather hawkish. Thus, if the removal of the expanded benefits proves successful in bringing people back into the labor force, it could lead to a rise in the unemployment rate. Although we believe that a rise in the unemployment rate will likely be temporary, it may also slow down the drive to remove policy accommodation. Therefore, a rise in the unemployment rate could be favorable for risk assets.

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Unrest in Colombia (July 12, 2021)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

When you find yourself surrounded by a squad of masked, black-clad fighters with their machine guns aimed at you, you can be pretty sure you’re about to have a bad day. The sense of foreboding was especially strong when this happened to me on a deserted road high up in the Colombian mountains, just after my jeep passed an abandoned one-room schoolhouse with “ELN Vive” spray painted on its wall, announcing that one of Colombia’s main rebel groups was active in the area. My only other feeling at the time was consternation: When my Colombian wife had talked me into letting her take our two young sons to spend the summer at her family’s coffee plantation outside the city of Manizales, she had assured me that it was perfectly safe. I was now on my way to pick them up and bring them home from this supposedly safe mountainside. As I watched the gunmen approaching my jeep, I realized that “safe” is a relative term for Colombians.

Once the soldiers had emerged out of the tall grass along the road and made my driver stop, their leader walked up and motioned for me to surrender my passport. In situations like this, the moment you hand over a U.S. passport is the moment you start to feel like you have a bullseye painted on your back. But as he examined mine, it gave me time to look more closely at the fighters. Their uniforms were all brand new and of the finest quality, including their Kevlar helmets. Their M16 rifles were so new they didn’t have a single scuff on them. The commander handed back my passport, assured me his squad would be patrolling nearby if my family needed help, and motioned me onward. I had just been rescued by Colombian solders trained and equipped by the U.S. Department of Defense under the “Plan Colombia” aid program.