by Bill O’Grady and Kaisa Stucke

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] It was another quiet overnight session. Chinese inflation data (see below) was roughly in line with expectations. U.S. equity futures are modestly higher this morning, and Treasuries are rallying a bit as well. If anything, market action is consistent with late summer.

However, there are a couple of news items that are interesting. At the end of July, Ylan Mui of the Washington Post wrote a piece for Wonkblog noting that FOMC members are slowly coming to grips with a world in which growth is persistently slow and inflation remains soft. Former Fed Chair Bernanke has picked up this theme and noted that FOMC member forecasts have been steadily edging lower.

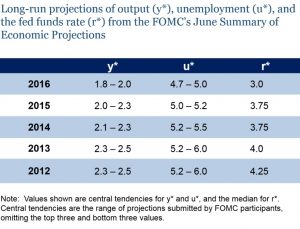

(Source: Brookings Institute, Bernanke)

(Source: Brookings Institute, Bernanke)

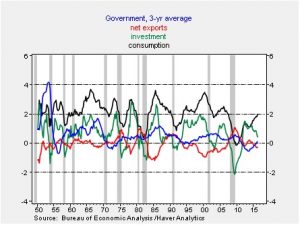

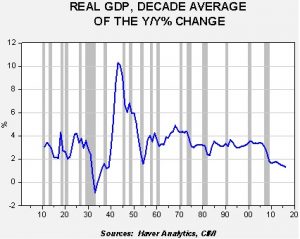

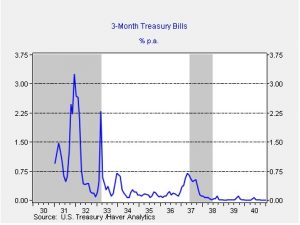

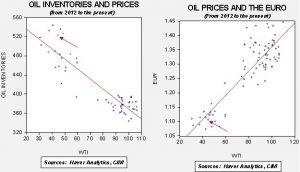

This chart shows the FOMC’s long-run projections for growth, unemployment and fed funds since 2012. Note that growth rate expectations have declined about 0.5%; there has been a similar decline for the “natural” rate of unemployment. The drop in growth and the lack of inflation has led to a long-run drop in the terminal fed funds rate. Why has this occurred? In one sense, it’s because earlier expectations continue to disappoint and so the committee is merely accepting reality. However, underlying these changes are, according to Bernanke, a change in the economy’s output potential. As productivity has declined, it takes more workers to generate the same level of growth, which would normally lead to higher wages and, eventually, higher inflation. But, if growth remains soft, the inflation lift never comes.

In our opinion, the missing part of Bernanke’s analysis is the dearth of discussion over slow wage growth. We suspect it is coming from three factors. First, technology is increasingly intruding into new areas of the labor market, reducing the number of people needed to operate the economy. For those areas not yet affected by technology, the threat tends to keep wages down. Second, globalization means that firms can search the globe for cheaper alternatives, which depresses wages. The third component is industry concentration. As firms merge, there are fewer staff positions available and firms develop market power over labor.

The bottom line is that the FOMC has become increasingly cautious about the economy’s future and thus doesn’t want to make a mistake by raising rates too soon or too much. Accordingly, the FOMC is likely to be hesitant to raise rates mostly because the economy isn’t behaving as it did prior to the 2008 Financial Crisis.