by Bill O’Grady and Thomas Wash

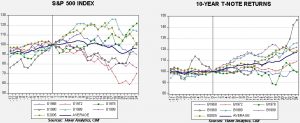

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] It’s employment day! We cover the data in detail below but the quick read is bullish. The key data point was a huge jump in the labor force, which increased 601k after falling 382k over the past three months. Thus, even with a rise in payrolls, the unemployment rate rose due to the increase in the labor force. The data is bullish for financial assets because it suggests there is remaining slack in the economy. Perhaps today is the day historians will mark as the beginning of the Great Trade War as the U.S. and China implemented tariffs against each other.

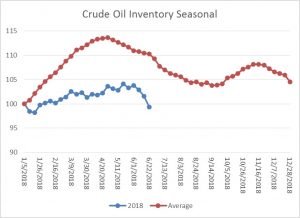

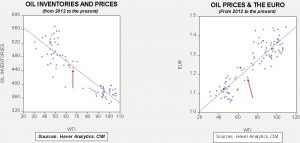

A note on our comment—we update the U.S. petroleum weekly data on Thursday but, this week, the numbers were delayed until yesterday due to the Independence Day holiday. Because of the length of the recap and our coverage of the employment report, we will delay our energy recap until Monday’s comment. Here is what we are watching:

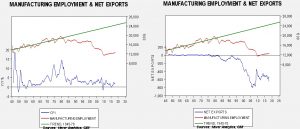

Trade wars: The $34 bn[1] of tariffs on China were implemented at midnight EDT.[2] China has undertaken similar measures. In 10 days, another $16 bn of tariffs will be added. And, President Trump upped the ante by suggesting he could apply tariffs to more than $500 bn in flow, essentially everything China exports to the U.S.[3] China is blaming the U.S. for the “war,”[4] which will only infuriate Trump, who holds the position that the U.S. is merely correcting what has been an unfair situation. We have talked about the trade conflict at length in recent weeks but one thing we want to reiterate is that winning a trade war is not about how much pain a nation can inflict on another but how much pain a nation can absorb. Note the difference between Europe and China. As we noted yesterday, the EU, at German urging, is considering ending tariffs on imported automobiles, something they would not have done without U.S. pressure. This suggests to us that the EU is simply not prepared to take the pain associated with a drop in car production. Consequently, they are suing for peace. On the other hand, China appears to be digging in for a long, protracted trade war.[5] The Chinese media is framing the trade war as the West’s attempt to contain China’s rise. In other words, Chairman Xi is planning on using nationalism to “steel”[6] his citizens for absorbing the pain by making the trade war more like a real war. Xi has often referred to the “century of humiliation” that began with the First Opium War in 1842. The Opium War narrative is that the Chinese failed to rally behind the emperor in 1842 and foreigners defeated and “carved up” the country and it could happen again if China fails to rally behind Chairman Xi.

In some respects, the timing of this trade war is unfortunate for China. The country is trying to deleverage while maintaining growth and the usual way to do this is to export one’s way out. The trade war will likely close that avenue of maintaining growth. At the same time, now Xi can blame any slowdown on Trump and can therefore use a slowdown to take the necessary steps to contain debt growth. In any case, China isn’t planning on backing down and our take is that the White House doesn’t think it can lose. Strictly speaking, we can’t. China has much more to lose because it runs a trade surplus with the U.S. However, a trade war will inflict pain and Americans will be less likely to rally around Trump when the economy begins to stumble because of trade disruptions. Thus, if winning a trade war is dependent upon the willingness to accept pain, China may be in a better position than generally expected.

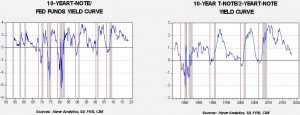

The Fed: The Fed minutes were released yesterday and they had a little something for everyone. The Fed intends to stay on its tightening path, although it did acknowledge the risk coming from the aforementioned trade war. Interestingly enough, Fed economists didn’t view the uncertainty surrounding GDP, unemployment and inflation to be different than the past two decades. We view this position as strikingly naïve. Market reaction to the employment data suggests a dovish response from the FOMC. This reaction is probably not warranted; after all, it’s only one month’s data in a notoriously volatile series. But, the key takeaway from the minutes is that the Fed is not altering its course.[7]

Brexit: PM May is meeting with her cabinet today[8] with the goal of establishing a unified vision of the economic and trading relationship the U.K. will have with the EU after Brexit. There is the potential for a breakup; watch for resignations. If some of her cabinet members quit, a leadership challenge is likely and there is a chance the government will fall. May has remained in office by weaving a perilous path between a hard and soft Brexit but, in the end, she leans toward the latter.[9] Elections could bring a Corbyn-led Labour government which would likely be profoundly bearish for U.K. financial assets.

Trump to Europe: The president travels to Europe next week and he blasted the Europeans at a rally in Helena, MT last night, which may be a forewarning of what his talks will be like.[10] The president is also meeting with President Putin,[11] which has raised fears not only with the U.S. establishment but also with European leaders. If the U.S. abandons NATO, the Europeans will be forced to defend themselves against the Russians.

Oil: A couple of quick notes and a reminder that we will recap the weekly data on Monday. First, there are growing doubts that the Saudis will ever introduce the Saudi Aramco IPO.[12] The key sticking point appears to be the scrutiny that going public would bring to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Saudi Aramco is essentially the funding arm of the KSA. When outside investors see how much profit is taken by the royal family, it would not only tell the Saudis where the money is going, but it would undermine the valuation of the stock. If the IPO isn’t going to happen, the Saudis will have less incentive to keep prices high and may decide to boost production and capacity to (a) take advantage of high prices, and (b) eventually undermine the shale revolution. Second, South Korea has suspended Iranian oil loading for this month, the first time since 2012, suggesting that U.S. sanctions are beginning to affect Iranian oil sales.[13]

[1] https://www.ft.com/content/5c5b66a8-80a6-11e8-bc55-50daf11b720d?emailId=5b3ef34663ab2e00040aceba&segmentId=22011ee7-896a-8c4c-22a0-7603348b7f22 and https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/business/china-us-trade-war-trump-tariffs.html?emc=edit_mbe_20180706&nl=morning-briefing-europe&nlid=567726720180706&te=1

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/bd99c39c-8024-11e8-bc55-50daf11b720d?segmentId=a7371401-027d-d8bf-8a7f-2a746e767d56

[3] https://www.cnbc.com/2018/07/05/trump-says-us-will-impose-16-billion-in-additional-tariffs-on-china-i.html

[4] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-china/china-state-media-slams-trumps-gang-of-hoodlums-as-tariffs-loom-idUSKBN1JW07L?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=newsletter_axiosam&stream=top

[5] https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-china-prepare-for-trade-battle-1530824054?mod=hp_lead_pos1

[6] See what I did there?

[7] https://www.wsj.com/articles/fed-expects-to-keep-raising-rates-ending-years-of-stimulus-1530813720

[8] https://www.ft.com/content/4e844a06-7f96-11e8-bc55-50daf11b720d?desktop=true&segmentId=7c8f09b9-9b61-4fbb-9430-9208a9e233c8#myft:notification:daily-email:content

[9] https://www.ft.com/content/36eafa08-804e-11e8-8e67-1e1a0846c475?segmentId=a7371401-027d-d8bf-8a7f-2a746e767d56 and https://www.ft.com/content/44fbf0e6-8041-11e8-8e67-1e1a0846c475?emailId=5b3ef34663ab2e00040aceba&segmentId=22011ee7-896a-8c4c-22a0-7603348b7f22

[10] https://www.axios.com/trump-nato-nightmare-defense-spending-europe-germany-74d2d010-e32a-40b2-8e71-920601f0e9a0.html

[11] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/world/europe/trump-putin-summit-election-meddling.html?emc=edit_mbe_20180706&nl=morning-briefing-europe&nlid=567726720180706&te=1

[12] https://www.wsj.com/articles/doubts-grow-aramco-ipo-will-ever-happen-1530813982

[13] https://af.reuters.com/article/energyOilNews/idAFS6N1R4016