by Thomas Wash | PDF

Mounting national debt and tightening financing conditions are pushing the US Treasury to rethink traditional funding strategies, and stablecoins have emerged as an unexpected contender.

Minutes from April’s Treasury Quarterly Refunding meeting reveal that officials are actively evaluating the use of stablecoins for buying US debt. This signals a strategic shift in government financing, blending innovation with necessity as the US recalibrates its fiscal approach in a changing global landscape.

Why Stablecoins?

Stablecoins are a type of cryptocurrency designed to maintain a stable value, typically by being pegged 1:1 to the US dollar, although any currency, in theory, could be used. Under the proposed GENIUS Act (recently passed by the House), the issued stablecoin must be supported by reserves that often include highly liquid assets like Treasury bills, insured bank deposits, and repurchase agreements (repos). Commercial paper has been used previously as a reserve, but if the legislation passes, then the reserve asset for stablecoins will be restricted.

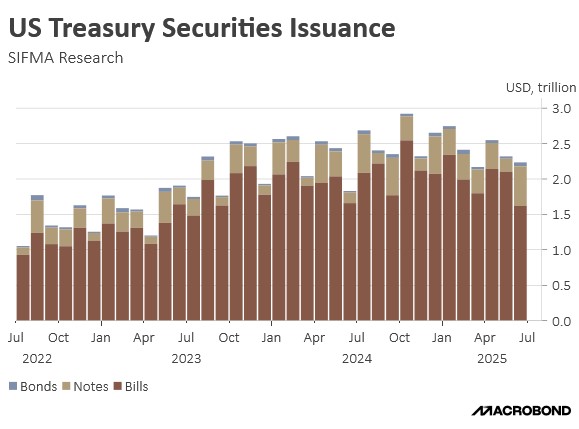

Widespread adoption of stablecoins could spur new demand for short-duration bonds, aligning with the Treasury’s recent pivot toward issuing shorter-term debt to fund spending. Currently, an estimated 80% of the stablecoin market, which represents about $200 billion, is invested in either Treasury bills or repos. Projections indicate this market could expand to $2 trillion by 2028 if legislation is enacted that creates a regulatory framework.

How Stablecoins Work

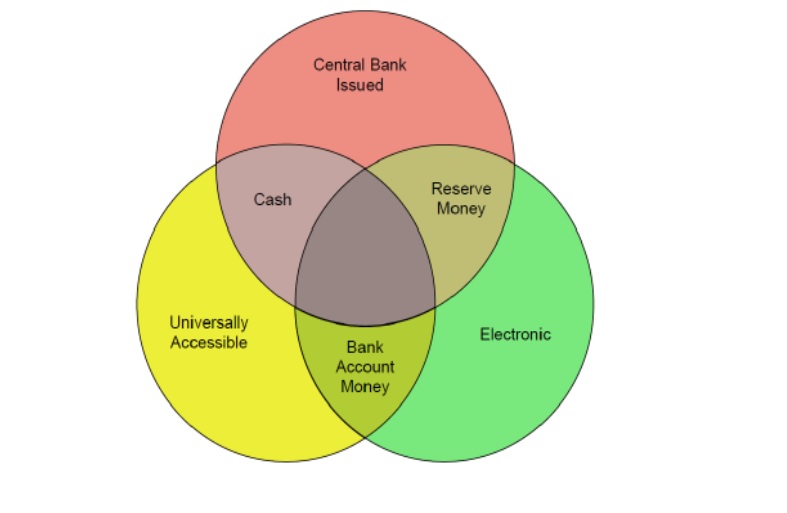

A stablecoin comes into being when a user exchanges another asset, such as fiat currency or a different cryptocurrency, with an issuer. Once the issuer receives this asset, they mint an equivalent amount of stablecoin and deposit it into the user’s account. These transactions are recorded on a distributed ledger (commonly known as a blockchain), which involves a network of participants.

The attractiveness of stablecoins lies in their use as a store of value. Their backing by real-world assets, such as fiat currency or other liquid instruments, allows the stablecoins to trade freely as a digital currency. This stability is maintained by the ability to convert the stablecoin back into its underlying reserve asset (e.g., US Treasurys) upon demand. In this way, stablecoins function similarly to money market funds with one important exception. Under current legislation, stablecoins cannot provide a yield to their holders. Doing so would make stablecoins a security.

Why Are Stablecoins Important?

Establishing a clear and enforceable regulatory framework is crucial for stablecoins to unlock their full potential as a reliable medium of exchange. As more individuals and businesses integrate stablecoins into their payment processes, a corresponding surge in demand for their underlying reserve assets, particularly US Treasury bills, is anticipated.

A core premise driving stablecoin adoption is their ability to offer individuals and entities worldwide exposure to the US dollar without requiring direct engagement with the traditional US banking system. This characteristic uniquely positions stablecoins as a potential alternative for efficient and cost-effective cross-border payments. By facilitating such transactions, stablecoins could further reinforce the US dollar’s dominant role in international trade and finance.

Market Ramifications

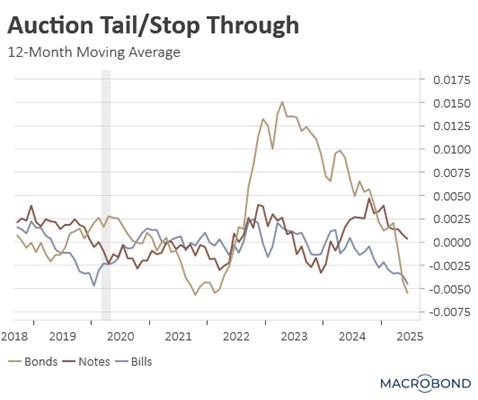

The increased use of stablecoins could facilitate the Treasury’s reallocation of funding away from long-term bonds in favor of shorter-duration instruments. This shift would not only improve Treasury auction performance but should also help exert downward pressure on long-term interest rates, thereby reducing overall borrowing costs across the economy.

The primary downside, however, is the possibility that stablecoins could attract capital that would typically flow into the traditional banking system, specifically money market funds, which have historically been a lynchpin of the financial system. Although, the inability of stablecoins to pay interest may reduce disintermediation. At the same time, the advent of stablecoins could force banks and money market funds to increase their yields. A significant concern we will monitor is the potential for stablecoin runs, given that some stablecoins have “broken the buck” during periods of uncertainty in recent years. This highlights the risk of instability if not properly managed.