Tag: Bessent

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – The Erosion of Exorbitant Privilege (February 2, 2026)

by Thomas Wash | PDF

Japan’s pursuit of aggressive fiscal stimulus has put it in a precarious position. Prime Minister Takaichi has called snap elections for February 8 to leverage her popularity and improve her parliamentary majority to pass a major tax cut plan. The market’s response, however, has been a haunting echo of the UK’s “Truss moment,” reflecting a broader crisis of confidence. Investors are signaling that even G7 governments can no longer count on a free pass for unfunded spending hikes, raising the risk of a sustained bond market pushback.

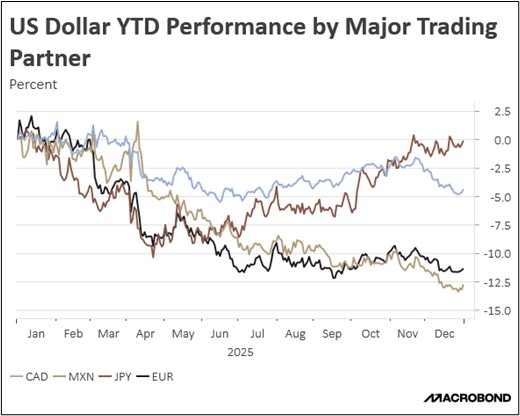

That warning turned concrete with a violent “twin sell-off” in Japan. Soaring government bond yields collided with the yen in freefall toward 160 against the dollar. The stress transmitted instantly to US Treasurys, a correlated sell-off severe enough to prompt US Treasury Secretary Bessent to confer with his Japanese counterpart, Satsuki Katayama. This episode delivers a stark market verdict: core developed nations are sacrificing long-term debt sustainability for short-term political stimulus. More critically, it forces investors to confront a once unthinkable possibility that the sovereign debt of advanced economies is beginning to mirror the structural fragility historically seen in emerging markets.

This twin sell-off is unique because it challenges the core distinction between developed and emerging markets, which is rooted in debt maturity. Historically, an emerging market currency crisis is precipitated when sovereign bond yields and domestic currency values move in opposite directions. Yields spike as investors flee, causing the currency to depreciate. Previous twin sell-offs signaled the collapse of investor confidence during the 1994 Tequila Crisis, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, and the recent volatility of the Argentine peso.

The mechanics of such a crisis differ fundamentally in developed markets, mostly due to the maturity structure of their sovereign debt. Unlike emerging markets, which are often forced to borrow via short-term instruments, developed nations have historically enjoyed the “exorbitant privilege” of issuing long-term debt. This extended duration insulates them from the immediate roll-over risk that often paralyzes emerging economies during a market shock.

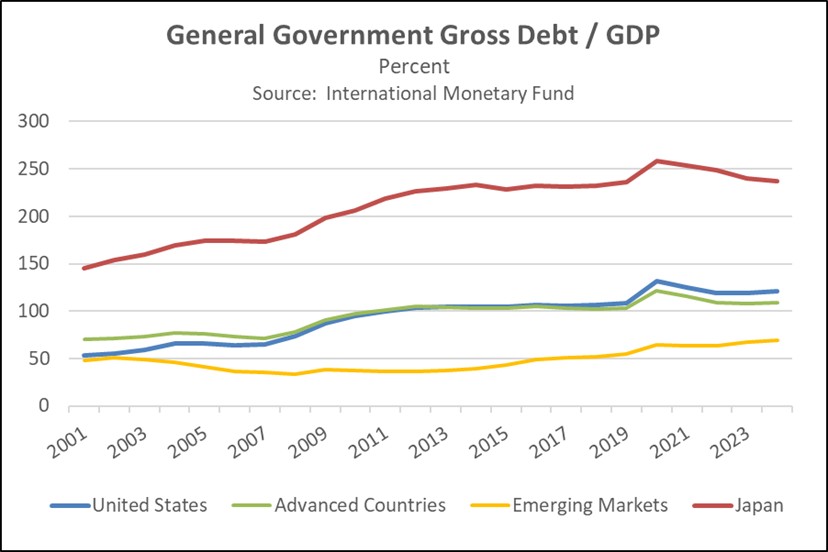

This privilege has afforded more than just insulation; it has effectively enabled developed nations to finance persistent, massive deficits without the immediate specter of a financial crisis. By issuing long-term debt denominated in their own reserve currencies, these nations have utilized a strategy of “extend and pretend,” rolling over maturing obligations while indefinitely deferring the structural reforms necessary for long-term solvency. This buffer is most glaring in Japan, which has sustained a gross debt-to-GDP ratio exceeding 200% for years with no imminent crisis in sight.

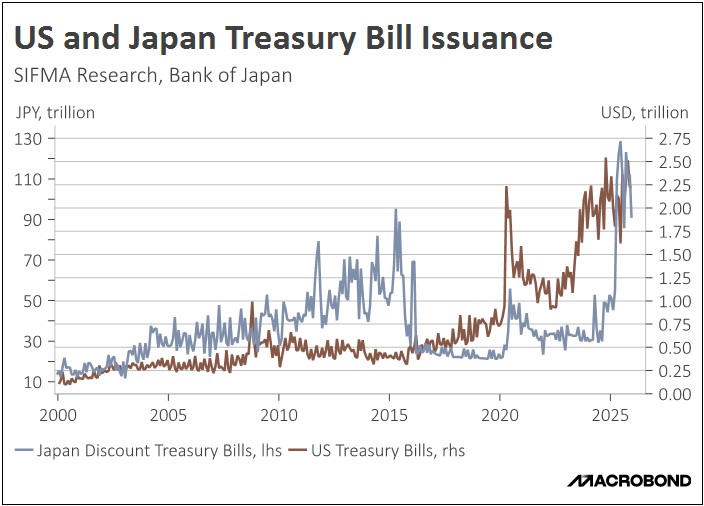

However, recent market volatility suggests that the era of unconditional trust in sovereign debt may be ending. A clear sign of this shift is the growing investor preference for shorter-dated securities, which is compelling governments to shorten their debt issuance profiles in response. For instance, Japan’s Ministry of Finance has moved to scale back the issuance of 40-year bonds and reduce 30-year volumes to stabilize the “super-long” end of the curve. Similarly, the US Treasury has significantly ramped up the share of Treasury bills to meet funding needs, a strategic pivot intended to provide relief to the long-term Treasury market amid fluctuating yields.

While the collective shift toward shorter-term debt temporarily suppresses long-term yields, it imposes significant systemic costs. It heightens the financial system’s sensitivity to monetary policy as frequent refinancing exposes institutions to immediate liquidity strains and rollover risk when rates rise. Ultimately, this concentration of short-term liabilities could handcuff central banks, forcing them to choose between fighting inflation and avoiding a market-wide liquidity crisis.

In this new era of heightened sovereign risk and policy constraint, portfolio management must adapt. A systemic crash is not inevitable, but the structural shift demands a strategic response. Practically, this environment may increase the appeal of non-correlated hedges like precious metals against currency debasement and inflation. Within fixed income, aligning with the prevailing supply-demand dynamic favors intermediate- and short-term securities. Above all, disciplined geographic diversification becomes more critical than ever to mitigate exposure to any single market undergoing a structural repricing.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #137 “Managing an Economic Slowdown” (Posted 3/31/25)

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – Managing an Economic Slowdown (March 31, 2025)

by Thomas Wash | PDF

Six months into his presidency, Reagan backed restrictive monetary policy to combat inflation. While the move initially drew criticism for its short-term economic pain, many viewed it as a necessary step toward long-term stability and growth. This optimism was ultimately vindicated, paving the way for Reagan’s landslide reelection in 1984. The lesson: an early-term recession, though difficult, can create strategic opportunities to push a bold and transformative agenda forward.

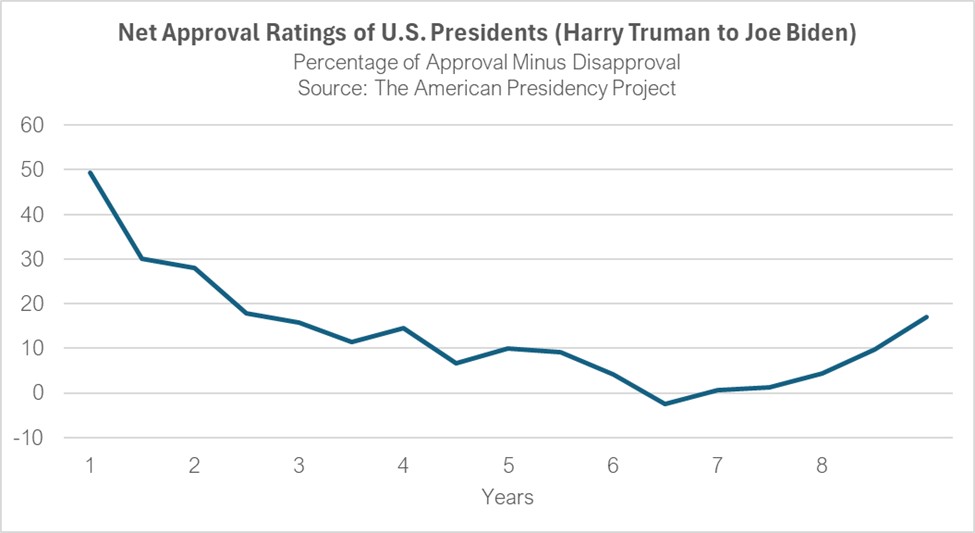

A president typically wields the greatest amount of political capital at the outset of their tenure. This period, often referred to as the “honeymoon phase,” is usually marked by peak public approval, fueled by the optimism and goodwill that was generated during the election campaign (see chart below). Supporters are often energized, and even those who may not have voted for the president often extend a measure of deference and give the new administration an opportunity to set the tone and pursue its agenda.

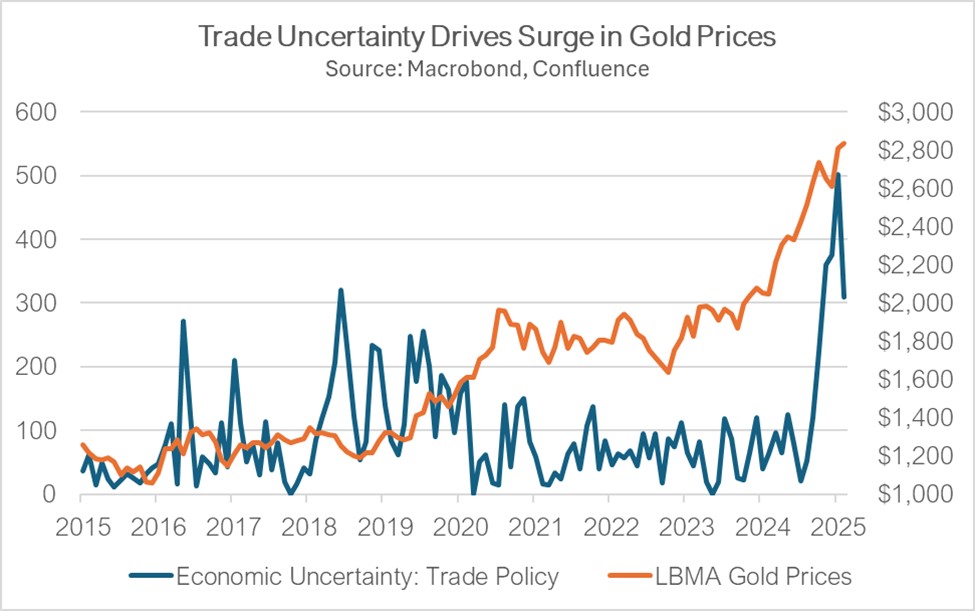

During this pivotal period, President Trump has escalated his aggressive trade war with the rest of the world. It appears that the administration’s strategy is to weather any associated short-term economic challenges — such as heightened market volatility caused by unpredictable trade policies and budget cuts designed to strengthen the government’s fiscal position — in order to achieve a broader goal of transforming the US economy from one driven by high consumption to one that prioritizes export promotion.

The administration’s ability to manage an economic downturn will be largely influenced by the capacity to lower long-term rates, especially in today’s high interest rate environment, as well as the fiscal flexibility created by recent efforts to curb government spending. Extending the 2017 corporate tax cuts could also provide businesses with a financial buffer, enabling them to adapt to the impact of new tariffs.

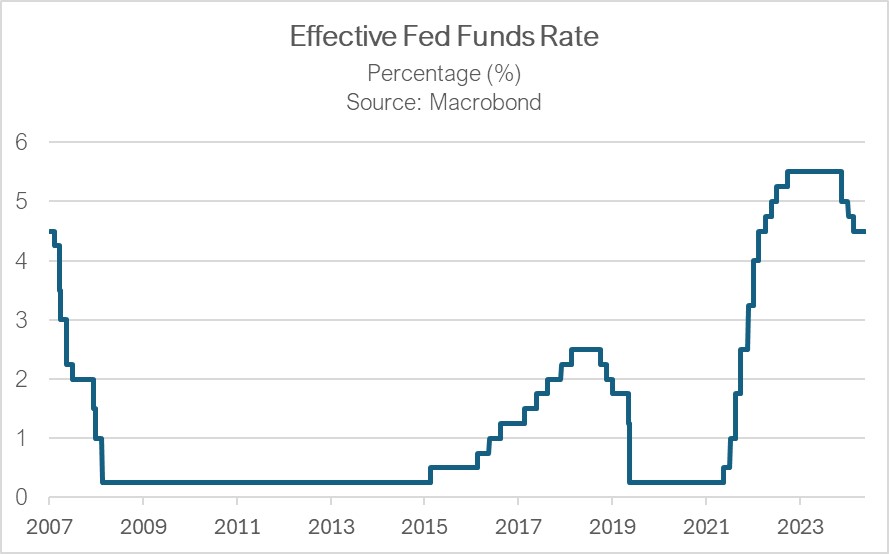

Importantly, the Trump administration is apparently counting on the Federal Reserve to serve as an economic safety net in the event of a severe downturn. While the central bank has already reduced rates by 100 basis points from their peak during the tightening cycle, it still has the ability to cut rates and restart balance sheet expansion, if needed. These measures could enable households to refinance their mortgages at lower rates, thereby improving household balance sheets and paving the way for higher spending.

That said, this strategy carries significant risks. For example, if the downturn persists for too long, it could potentially trigger a financial crisis, undermining household confidence and consumers’ willingness to spend. In such a scenario, the government might be forced to take more drastic measures, such as implementing a bailout or fiscal stimulus to restore confidence and stabilize the economy. Such spending could lead to a sharp increase in government debt, raising concerns about its long-term sustainability and potentially leading to a period of stagnating growth.

While there is no reward without risk, the president’s ability to slow the economy to implement longer-term, sustainable reforms also hinges on his capacity to embrace short-term political pain in exchange for long-term gain. For example, we note that while the Reagan recession was relatively short, it resulted in Republicans losing House seats to the Democrats. This scenario could present considerable challenges for the Trump administration. Unlike President Reagan, who successfully advanced his agenda by working across the aisle, Trump may find himself constrained by a lack of bipartisan cooperation given the current political climate. As a result, he may be more incentivized to ensure that Republicans regain and possibly add to their majority in Congress, something Reagan was not able to do in the mid-term elections during his first term.

In such a scenario, the president would need to pivot strategically, prioritizing the delivery of a tangible and widely recognized victory to the public ahead of next year’s primary election to sustain momentum and galvanize support. This could take the form of highlighting major achievements, such as breakthroughs in trade negotiations or the successful passage of the long-awaited tax bill.

We continue to believe that equities will be able to produce attractive long-term investment returns, especially if the Trump administration achieves its long-term goals. However, given the current level of uncertainty and the risk of near-term economic disruptions, we also see gold as an attractive option. Additionally, the potential for a decline in long-term interest rates could make this an opportune time to extend duration in government fixed-income securities.