Daily Comment (November 30, 2018)

by Bill O’Grady and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] Good morning! It’s a very quiet market this morning. Equities continue to consolidate in front of this weekend’s G-20 meeting. Here is what we are watching today:

The G-20 and China talks: We expect some sort of short-term accommodation at this weekend’s meeting. We look for the U.S. to delay implementing the tariff hike on China and postpone expanding tariffs on the rest of Chinese imports. China will offer to buy some American goods in return. However, the key issues, such as technology transfers and intellectual property theft, won’t be resolved. Although we do expect some modest agreement, we note that Peter Navarro, the president’s hardline trade advisor, has now been invited to the Saturday dinner with Xi. This may be signaling a harder line on China because he was initially kept off the seating chart. In our view, China and the U.S. see each other as strategic competitors. So, we may see a truce, which the financial markets generally expect, but a long-term resolution isn’t likely because it isn’t really possible. U.S. and China hegemonic competition is now in the open and will be a major issue for the foreseeable future. At the same time, as we detail below, Chairman Xi probably needs an agreement more than President Trump does, at least in the immediate term.

China’s economy: China’s official manufacturing PMI data came in weaker than expected, coming in at 50.0 in November, down from 50.2 in October. The official data is generally considered less reliable than the Caixin PMI report, which comes out on Monday. The fact that the report is now resting on the expansion line shows that the Chinese economy is under pressure. Although American trade policy is partly to blame, deleveraging is probably playing a larger role.

This chart shows China’s annual M1 growth along with the yearly growth of outstanding credit. Up until 2011, the two measures tended to follow each other closely. However, the response to increased money supply growth in 2016 was modest at best, suggesting the PBOC’s ability to stimulate is weakening. Further evidence is seen when comparing money growth to industrial production.

Why is this happening? One potential reason is that as China’s economy matures, it can no longer rely on investment spending to boost growth. In other words, until a few years ago, China’s economy could absorb new investment even if it wasn’t necessarily needed. But, if we have reached a point of saturation then monetary policy is essentially “pushing on a string.” This is why China’s trade issues with the U.S. are so important. After the Great Financial Crisis, China offset the loss of exports with an investment boom. If that isn’t working and consumption hasn’t improved, about the only sector left to support growth is the export sector and the Trump administration is essentially closing off that avenue.

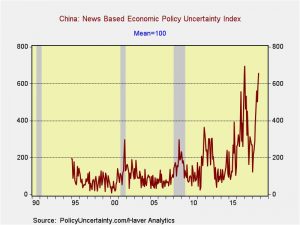

Perhaps the biggest issue is uncertainty. A group of U.S. professors[1] have created a basket of uncertainty indicators that are constructed by scanning articles about policy, economics, etc. They have created these indices for a variety of countries, including China. The index, which uses the South China Morning Post out of Hong Kong as its principal source, suggests that economic uncertainty is sharply elevated.

This data suggests the Xi government is facing a serious sentiment problem and needs to show that it can stabilize the economy. Unfortunately, it isn’t obvious what can be done if the credit impulse isn’t working; therefore, Xi may be more inclined to make a deal with President Trump, at least to support the economy in the near term.