Daily Comment (May 9, 2017)

by Bill O’Grady, Kaisa Stucke, and Thomas Wash

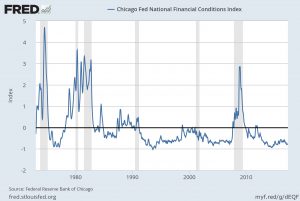

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] There isn’t a lot of economic or market news this morning. Most of the market talk is swirling around the low level of the VIX. Our contention is that the Fed is actively trying to suppress financial stress; in doing so, the need for insurance against stress, essentially, the VIX, isn’t as necessary. The problem that arises is that there are periods, such as the Great Financial Crisis, when investors lose faith in the Fed’s ability to contain stress. In such periods, stress soars and, consequently, so does the VIX.

This chart shows the Chicago FRB National Financial Conditions Index, one of the many different stress indices. It has 105 different variables, including the level of interest rates, spreads, volatility indices for various financial products, precious metals prices, etc. A reading of zero is normal; any reading under zero suggests low financial stress. Since the early 1990s, it appears the Fed has actively tried to prevent stress from developing. The trouble with this policy is that it breeds complacency, encouraging investors to take on increasing risk, confident in the view that the central bank is protecting them from danger.

Part of the problem with the VIX is that it suffers from time decay. In other words, like most insurance, each day that the insurance isn’t needed the payment for the protection is permanently lost. Simply recognizing that the VIX is low doesn’t necessarily mean that it should be bought; if conditions remain stable, it will continue to fall. We view the low VIX as an indication of investor complacency but would argue that, at heart, it’s really a reflection of the conduct of monetary policy.

There are three geopolitical concerns we are monitoring today.

A surge in Afghanistan? It appears the administration is considering an increase in U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan. Over the past couple of years, the Taliban has been steadily gaining control of the countryside. Advisors to the president are putting together a plan to boost U.S. troop presence with the goal of forcing the Taliban to negotiate a settlement. Currently, it appears that the level of troops is too small to be consequential but large enough to be a target. However, it’s difficult to see how an increase of a few thousand troops will change the Taliban’s battle plan, which has always been to outlast the U.S. In fact, this has generally been the battle plan of insurgents in Afghanistan throughout history. Although we harbor serious doubts that escalation will work, the political danger is that much of the president’s political support came from those who supported a de-escalation of U.S. hegemony. Escalating in Afghanistan flies in the face of that promise and could prompt a political backlash.

A new president in South Korea. Exit polls suggest that Moon Jae-in of the Democratic Party will become South Korea’s next president. He is replacing the disgraced Park Geun-hye, who faces corruption charges. South Korea tends to oscillate between conservative hardliners and more liberal leaders. Park was a conservative who conducted a hardline policy with North Korea. Moon is expected to be more conciliatory with the Kim regime. History shows that neither stance seems to work all that well with North Korea. At the same time, the incoming Moon government will face a tricky diplomatic situation with the U.S. The Trump administration has been very critical of the free trade agreement with South Korea and has threatened the South Koreans with a bill for the THAAD missile defense system the U.S. recently installed on the peninsula. Thus, the incoming Moon government will likely enjoy a very short honeymoon.

How will Macron govern? The new French president now faces parliamentary elections on June 11 and 18. The goal of any French president is to have a majority of seats in the legislature so the government is unified. However, Macron’s party is new and, at this juncture, has no seats in the legislature. Although Macron has indicated his new party will have a candidate for every seat, it is difficult to see how he can assemble such a roster unless there are massive defections from the major parties. So far, that hasn’t occurred. There is still about a month before the first round of elections are held but the most likely outcome is a divided government where Macron will have to work with a prime minister who isn’t from his party. If there is disarray in France, the parties of the extreme left and right will tend to gain power.