Daily Comment (May 31, 2019)

by Bill O’Grady and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] Good (?) morning! It’s ugly out there this morning; markets are in full risk-off mode, with all the flight to safety assets (yen, gold and Treasuries) rallying, while equities and commodities are falling. A surprise new tariff was announced on Mexico. Chinese data underwhelms and Beijing is preparing to retaliate against U.S. trade and technology policies. Here are the details and more:

The Mexico tariffs: The White house announced a surprise 5% tariff on all Mexican imports; they are scheduled to be implemented on June 10 unless Mexico stops the flow of Central American immigrants to the U.S. border. Financial markets did not take the news well. The MXP plunged, 10-year Treasury yields broke 2.20%, the two-year briefly fell under 2%, German 10-year Bunds fell to their lowest level on record, at -0.204%, and equity markets worldwide stumbled. U.S. automaker shares fell especially hard on the Mexico news. Mexican President AMLO does not look like he will buckle in the face of the tariff threat. Here are some potential ramifications of this move:

- Mexico is an important trading partner; in terms of goods only, year-to-date, it is the largest trading partner with the U.S. The increase in tariffs will be modestly inflationary at best and disruptive at worst. This assumes no retaliation from Mexico. We don’t expect Mexico to apply widespread tariffs on the U.S. but it could target sensitive areas. However, it is also possible that AMLO could counter Trump’s position by simply opening the borders and encouraging increased Central American immigration. Things could get worse, in other words.

- UMSCA is in deep trouble. How can Mexico and Canada agree to a free trade deal when the U.S. is willing to unilaterally use tariffs as a punitive tool for issues unrelated to trade?

- Mexico was increasingly looking like a safe harbor if trade relations with China deteriorated further (we admit that this was our position). This action seriously undermines that outcome.

Overall, this surprise move further isolates the U.S. on trade issues. The White House is now engaged in trade conflicts on multiple fronts and it is hard to see how these actions are friendly to risk assets.

China prepares for more aggressive retaliation: China is preparing steps to take against U.S. tech restrictions. According to reports, it is creating a “blacklist” of U.S. firms that it views as taking hostile actions against China, which will seriously undermine their ability to maintain business in China. As we noted yesterday (and will have more on this in next week’s WGR), exports of rare earth products to the U.S. may be restricted. Huawei (002505, CNY 3.58) has reportedly ordered its employees to cancel contacts with U.S. firms. Retaliation is starting to move beyond just “tit-for-tat” tariff responses.

The broader story: We are starting to see the outlines of what the administration is moving toward, which is deglobalization. The White House has been indicating all along that it wants to see more production sourced in the U.S. This position is consistent with the multi-front trade war that is underway. There are reports of U.S. manufacturers starting to move production out of China. The idea seemed to be that these facilities would move to Southeast Asia or Mexico, and that could still happen. But, as the Mexico tariffs show, the U.S. can move with little warning against a foreign nation over all sorts of issues. The only truly secure supply chain may be in the U.S.

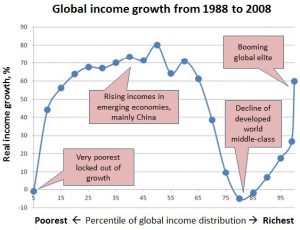

Essentially, there is a case to be made that the White House is attempting to use tariffs to address the famous “elephant chart,” at least for the U.S.

This chart shows inflation-adjusted income growth by income distribution across the world from 1988 to 2008. One can clearly see that the rise of the emerging world (China, India, etc.) has come at the expense of the Western middle class. The upper income elites in the West have also benefited. This chart illustrates one of the reasons for the rise of Western populism. Resourcing production back to the U.S. would be an attempt to pull down those in the 25%-65% area and lift the 75%-90% part of the chart. Since globalization is only part of this story (deregulation and automation are also important), tariffs and other trade restrictions, by themselves, might not work. Nevertheless, that likely won’t stop the administration from trying.

It should also be noted that the resourcing policy, i.e., bringing production capacity back to the U.S., might fail as a foreign policy. In other words, if the U.S. has a policy goal to thwart China’s belt and road project by increasing U.S. influence in Southeast Asia, then it might be better to support the shift of production out of China and into that region. However, that would likely work at cross-purposes to breaking down the elephant chart.

A key question for the 2020 elections is whether President Trump is an anomaly or a trend? The political establishment is desperately trying to confirm that he was a fluke. We disagree and would offer that even if Trump doesn’t win re-election the trend in policy to address the elephant chart is the new normal.

The Fed’s conundrum: GDP is running over 3%. Inflation remains tame. Financial markets are screaming for policy easing. So far, the FOMC continues to preach patience. This has also led some governors to make nonsensical statements. For example, Randy Quarles noted that the Fed’s primary job isn’t financial stability. We know what he meant—the Fed shouldn’t create the impression of a “Fed put,” coming to the rescue every time equities stumble. However, the origin of central banking was to create a backstop against bank runs; so, yes, the Fed’s primary job is financial stability, in the sense that the Fed needs to keep the banking system stable. Failure to do so means that no matter how well the Fed does everything else, it will have failed at its most important job.

The financial markets are clearly telling the Fed it needs to cut rates ASAP. A key problem for the Fed is discerning whether the financial markets are accurately projecting that the White House’s trade and technology policies are dramatically increasing the odds of recession. If the financial markets are right, and the FOMC wants to extend the expansion, then it needs to act. Then again, cutting rates creates two other problems. First, given all the pressure the president has put on the Fed to cut rates, will a rate cut for good reasons look like a surrender? In other words, will a rate cut lead to the impression that policymakers acquiesced to the president and thus undermine their independence? Conversely, if they hold steady and the financial markets are correct in their assessment of the outcome of trade policy, is a recession better than the impression of being politically undermined? Worse yet, if the Fed allows a recession to occur, will Congress and the White House simply end Fed independence and make the central bank the facilitator of Treasury borrowing as it was prior to 1951? Second, should the Fed ease policy in the face of what it sees as ill-advised trade and technology policies? In other words, if the goal of maintaining the expansion forces monetary policy to accommodate what it sees as inappropriate trade and technology policies, what’s the point of being independent? Imagine in the future that there is a White House aggressively using an MMT model to boost fiscal spending; should the Fed stand against that policy or accommodate it?

In the face of such paralyzing uncertainties, the path of least resistance is to do nothing. This path probably does increase the likelihood of recession.

Odds and ends:There are reports, thus far unconfirmed, that Kim Jong-un has executed Kim Hyok Chol, who led negotiations for the February summit in Hanoi. Chancellor Merkel gave a speech at Harvard that was deeply critical of U.S. foreign policy. Despite the proximity to Washington, she did not visit there. Belgium is beginning the process of forming a new government; deep divisions between the Flemish and the Walloons have made forming other governments very difficult.