Daily Comment (June 21, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] | PDF

Happy Monday, the day after the summer solstice. Days will get shorter from here! We are watching the destruction waged by TS Claudette that moved through the Southeast over the weekend. The storm is on its way back to the Atlantic. We are getting a reflation trade bounce this morning, although we have little faith it will hold. Our coverage begins with the Iranian election. A deeper dive into Fed policy follows. There was a surfeit of political news from Europe, which we cover next. China news follows. Our international roundup comes next; economics and policy follow, and we close with pandemic news.

Iran Presidency: As expected, Ebrahim Raisi won the presidency easily. It was mostly rigged, as the Guardian Council eliminated nearly all the candidates and two conservatives withdrew from the race on Thursday. Turnout was below 50% of voters, which does undermine his legitimacy. Raisi is something of Ayatollah’s Khamenei’s executioner; as a prosecutor, he has overseen hundreds of executions.

The focus now shifts to talks on the U.S. returning to the nuclear deal. There is an element of a “Nixon to China” moment. Only an Iranian hardliner can make a deal with the U.S. because that person has political cover. A moderate would be criticized by the conservatives. In addition, Ayatollah Khamenei likely wanted a hardliner like himself to get credit for the lifting of sanctions. Of course, there is the awkwardness that Raisi is under U.S. sanctions.

When Obama made the deal, it appears he saw it as an opening gambit to eventually give Iran the role of regional hegemon. This would finally allow the U.S. to move on from the Middle East and focus on the Far East. Obama assumed Clinton would win in 2016 and negotiate a broader agreement. When Trump won, the Arab states and Israel moved quickly to isolate Iran and were successful.

As we move closer to a resumption of the agreement, its flaws will only be highlighted. The U.S. would like a broader agreement that would include curtailing Iran’s missile program and its support of proxies throughout the region. There is little chance Iran will give that up. Iran wants assurances that a new administration won’t again withdraw from the agreement. Since the Iran deal isn’t a treaty (which requires a two-third’s majority in the Senate), there is no guarantee a new administration wouldn’t withdraw again. Although we suspect that the U.S. will return to the agreement, it probably won’t matter all that much. Only nations like China and Russia will invest there, because any other nation knows that in 2024 the deal could be off. There is fear in the oil markets that the return of the Iran deal will be bearish due to increased supply. Any price weakness from that news isn’t likely to last.

The Fed: The repercussions of the change in the FOMC’s tone continue to affect financial markets. On Friday, after we published, St. Louis FRB President Bullard delivered a rather hawkish interview on CNBC. As we noted on Thursday, the dots plot pretty much ended the Fed’s earlier narrative of no hikes through 2023, and no amount of discussion by the Chair at his press conference could undo the damage. The market’s reaction has been swift and unmistakable. The reflation trade is being unwound. Commodities are under pressure, stocks fell, and the dollar appreciated. Perhaps the most profound change has been in fixed income, where the yield curve flattened rapidly.

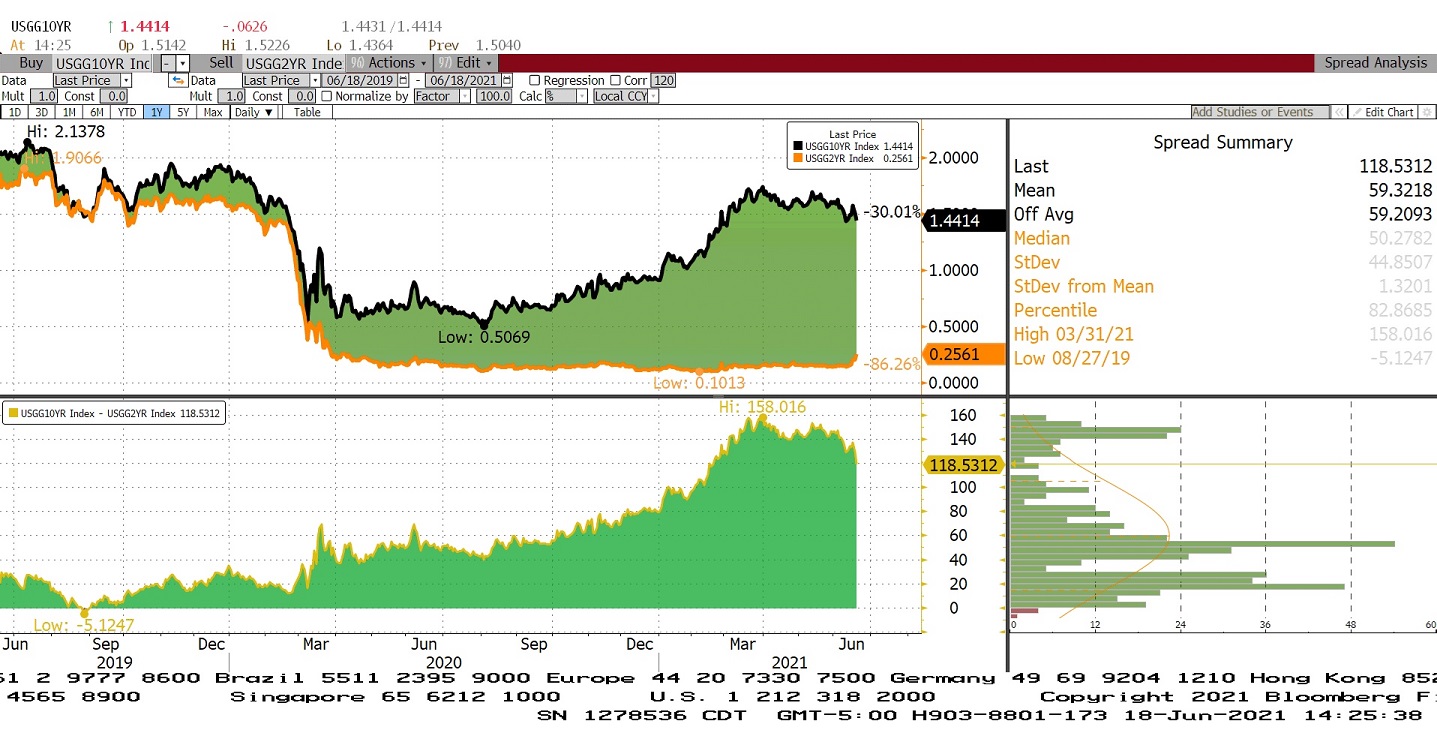

First, the 10-year/2-year spread:

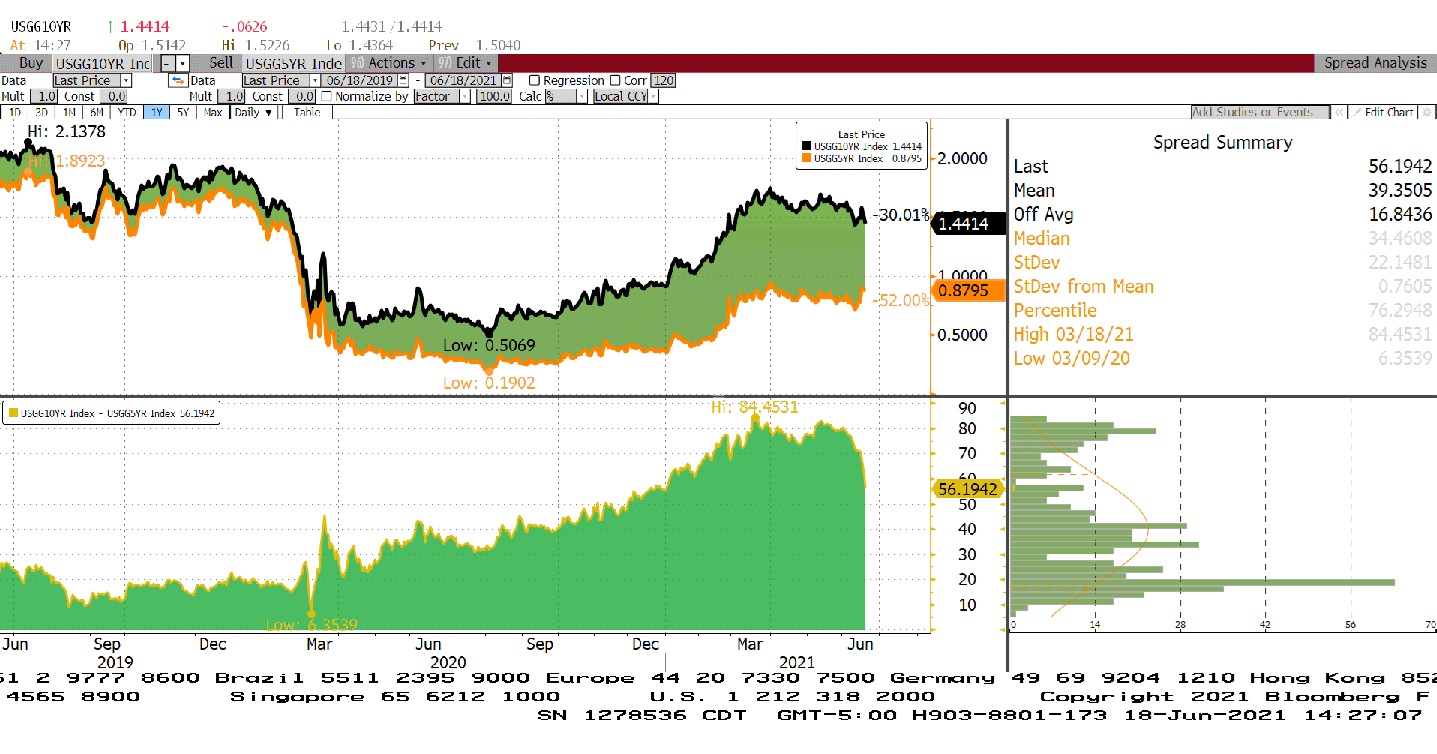

Next, the 10-year/5-year:

Although we are still a long way from inverting, the decline is unmistakable.

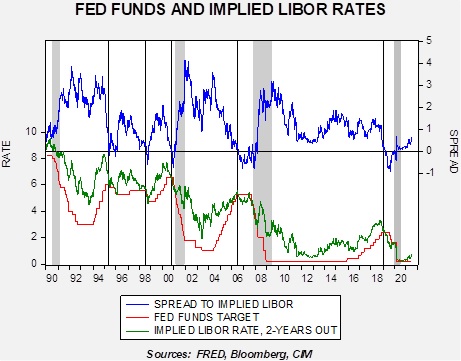

Meanwhile, the LIBOR futures are not yet factoring in rate hikes but are rapidly moving to a neutral position.

The two-year deferred Eurodollar futures have added 30 bps to the implied rate over the past week. Our model that incorporates the economy with Eurodollar futures suggests that short-term interest rate futures have not begun to build in tightening but are moving in that direction.

What happened here? It appears that Powell was trying to engineer a regime change at the Fed, shifting from an exclusive focus on inflation suppression to a greater consideration of full employment. The dispersion of the dots plot would argue that Powell has a rebellion of sorts on his hands. At the same time, we note that not all members of the FOMC have turned hawkish; Minneapolis FRB President Kashkari is still calling for a steady policy through 2023.

- Regime changes need different economic paradigms. The Phillips Curve dominated the Fed in the 1960s and 1970s. It is important to remember that Paul Volcker adopted monetarism by targeting the money supply and allowing fed funds to find their own level. Had he announced 19% fed funds in January 1981, he probably would not have survived. However, by saying the focus was on the money supply, it was the “market” that set the rate. This is obviously disingenuous (there is nothing sacred about a money supply target), but it gave him cover for doing something controversial. Powell has tried to change the regime by talking about an inflation target over a cycle and by a fully employed labor market. But he has never defined what these terms mean. By doing so, he hoped to give the FOMC maximum flexibility. By failing to set parameters, it was never clear when goals were close to achievement. So, when it came time to “stare down” the current spike in inflation, he apparently didn’t have the tools to sway a majority of the FOMC members.

- Earlier chairs never had to deal with the transparency that is now in place. We know from biographies that earlier Fed Chairs faced criticism. But then again, the disagreement wasn’t so public in the past. Thus, markets were forced to estimate the degree of dissension. For example, if Greenspan had dots in the late 1990s, it probably would have looked like he was facing a rebellion. After all, several members, including Janet Yellen, wanted to tighten credit.

- We suspect Powell lacks the theoretical credibility to sway the members. He isn’t an economist. Although that may not be necessary for much of the job, in this circumstance, the lack of intellectual credibility is damning. To note, he has very good relations with Congress. He consults with members regularly and is well-liked. Yet, when a Chair is standing up against orthodoxy, he must show he can argue the point. Volcker was able to credibly argue for money supply control. Greenspan could delay rate hikes in the late 1990s by arguing that productivity gains would keep inflation suppressed. Powell lacks credibility in this area, and when the economic orthodoxy (Summers, Dudley, and El-Erian) constantly warns that the Fed needs to address rising inflation, Powell is unable to craft a response. He is apparently unable to control the committee either.

Although commentators correctly point out that the Fed actually hasn’t “done” anything yet, this is misleading. The flattening of the yield curve and the rise in Eurodollar futures rates will affect borrowing costs and potentially slow the economy. Is the orthodoxy right? It depends on the path of inflation. If inflation is transitory, the Fed has made a mistake; the current turmoil is unwarranted. If inflation expectations are rising, then tightening is the correct action, and we can expect the dots to steadily build in rate hikes.

For markets, the reflation trade—weak dollar, strong commodities, small caps over large caps, value over growth, and international over domestic—is in question. There are still elements that argue for reflation; it’s not just the Fed that drives the trade. Nevertheless, the Fed’s shift will lead to a recalibration of the position.

The EU: Local elections show a recovery of the center-right, Sweden’s PM facing a no-confidence measure, and the DUP leader resigns.

- France held local elections over the weekend, and the results were surprising. Macron’s party didn’t do well; neither did Le Pen’s. Instead, the Republicans carried the day. Conventional wisdom suggests that Macron and Le Pen will be the leading candidates for president in the next elections, but this local result may signal that French voters have had enough with non-establishment parties.

- A dispute of rent control has led the Left Party in Sweden to pull out of the coalition, triggering a no-confidence vote. PM Löfven lost this vote, making him the first in Swedish history to lose in this fashion. He may try to form a new government, but if this effort fails, new elections will be held.

- The leader of the Northern Ireland DUP, the loyalist party, resigned late last week. Edwin Poots resigned after making concessions to the republican parties. These concessions, which centered around Sinn Fein’s demand for wider use of the Irish language in Northern Ireland, angered the DUP members. His resignation may force Westminster to retake control of Northern Ireland’s legislature.

- Poland claims it was hit with a Russian cyberattack which revealed emails from government officials.

- The EU agrees to increase sanctions on Belarus regarding the recent hijacking of a civilian aircraft to detain a government critic.

- Although the German Green party has become more centrist over time, its recent election manifesto stayed true to its environmental roots. It has been slipping in the polls, probably on fears that new regulations will hurt the economy.

China: Germany is reluctant to oppose China, and the world is overly dependent on Taiwan for semiconductors.

- In President Biden’s recent visit to Europe, he tried to build a coalition to counter China. Germany’s CDU leader has pushed back against this idea, showing that Germany is reluctant to disrupt its relations with Beijing and harm its investments in China. Despite the apparent lack of progress, Beijing remains furious about U.S. and NATO talks concerning containing China.

- We recently published a series of WGRs on Taiwan and the overdependence on this island for semiconductor production. The WSJ published a weekend report on this issue.

- Beijing is issuing new rules for the construction of commodity indexes. Although this may be a bid to standardize these indicators, we would not be shocked to see if they also minimized price increases.

- As birth rates plummet in China, Beijing is thinking about ending all restrictions on family size by 2025. We strongly doubt this will make much difference.

- Chinese high-yield bond prices are falling on fears of default. Index yields have hit 10%.

- China has expanded its crackdown on bitcoin mining.

International roundup: New sanctions on Russia, North Korea is threatening the U.S., and Brazil is dealing with drought.

- President Biden’s meeting with President Putin seems to have gone remarkably well. This is due, in part, to skillfully reducing expectations to the point where almost anything short of a blowup was seen as a success. It also seems that Biden has no illusions about getting along well with Putin, and therefore, both nations can pursue their interests on a clear-eyed basis. So, no great reconciliation, but a position where each party understands the other.

- Despite these talks, the U.S. is preparing additional sanctions due to the treatment of Alexei Navalny.

- Last week, we noted North Korea was probably facing severe food shortages if not famine. Almost on cue, Kim Jong Un is getting belligerent. When facing a crisis such as this, Pyongyang often threatens its neighbors in order to extract aid.

- Brazil is dealing with a crippling drought, said to be the worst in 90 years. Hydroelectric power is being curtailed, and crops are threatened.

Economics and policy: Tech remains under regulatory scrutiny, and a global tax deal may be unveiled by the end of June.

- The tech world is beginning to notice that its lobbying efforts are not achieving desired results.

- Left-wing populists in Congress are unveiling a large fiscal spending package designed to expand health care coverage. We don’t see how they have the votes to pass it in its current form.

- Sometimes, the U.K. acts as a harbinger for the U.S. In Britain, like here, companies are struggling to fill positions in the post-pandemic environment. Part of the U.K.’s problem may be due to Brexit, which has curtailed immigration.

- Treasury Secretary Yellen indicated that the U.S. would not back the global corporate tax plan if China is given carve-outs. A deal is expected by the end of this month. If so, it would pave the way for a domestic hike to corporate tax rates.

- The Fed’s shift in policy is a factor hitting timber prices and bitcoin.

- If banks pass the Fed’s stress tests, they hope to boost cash returns to shareholders.

COVID-19: The number of reported cases is 178,528,742 with 3,867,050 fatalities. In the U.S., there are 33,542,382 confirmed cases with 601,825 deaths. For illustration purposes, the FT has created an interactive chart that allows one to compare cases across nations using similar scaling metrics. The FT has also issued an economic tracker that looks across countries with high-frequency data on various factors. The CDC reports that 379,003,410 doses of the vaccine have been distributed with 317,966,408 doses injected. The number receiving at least one dose is 177,088,290, while the number of second doses, which would grant the highest level of immunity, is 149,667,646. The FT has a page on global vaccine distribution.

- The Delta variant, which emerged from India, is rapidly spreading through the EU. It has already delayed the U.K. reopening and is threatening the continent’s plans as well. Russia is reporting a surge in cases tied to this variant as well.

- Brazil has suffered 500,000 COVID-19 fatalities.

- Japan will limit attendance to Olympic events to 10,000. An Olympian from Uganda tested positive for the virus upon his arrival in Japan.

- Moderna (MNRA, USD, 199.19) says it will boost the production of its vaccines.

- We have been tracking the lab leak origin theory of COVID-19 for the past few months. The theory has been downplayed by numerous researchers; however, there is growing concern that these scientists may not be unbiased. In Wuhan, the lab was conducting “gain of function” experiments on various viruses. These experiments, in part, manipulate the virus to increase its potency to determine how it might evolve to become more dangerous. The practice, obviously, is controversial. The research industry attempts to deal with the issue by arguing it has strong safety protocols. The fear among researchers is that if COVID-19 did escape from a lab due to inadequate safety procedures, it could lead to a halt of such studies. So, we may not be getting a clear read from these scientists regarding the origin of the virus. There is a history of such deception.