Daily Comment (January 6, 2020)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EST]

Happy Monday! It’s another risk off morning, as issues surrounding Iran dominate the news and the markets. We update the situation in the Middle East this morning. In other news, Hong Kong has a new administrator and Phase One of the U.S./China trade deal should be signed by the 15th. Here are the details:

Iran: The funeral of Qassem Soleimani continues in Iran to massive crowds. In the wake of the operation that killed Soleimani, here are the items we are watching most closely:

- Iran’s retaliation—we expect Iran’s retaliation to the event to be potentially broad. We list some of the potential areas of risk below:

- Iran announced it is essentially ending the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, commonly known as the Iran Nuclear deal. This is no huge shock; Iran had been slowly violating the terms of the agreement in response to U.S. sanctions. However, officially ending it does have ramifications. If Iran “sprints” toward developing a deliverable nuclear weapon it will likely force Israel to at least consider direct air strikes on suspected nuclear sites. In the past, an Israeli attack was difficult to coordinate as the raid would have to use airspace of unfriendly nations. However, under the current situation, we would expect Saudi Arabia to be more than open to allowing overflights. We should also note that “deliverable” doesn’t necessarily mean a warhead on a missile; Iran might have a device it could detonate at ground level, carried by a proxy. This plan would have its own complications but can’t be completely ruled out. A “dirty bomb” could be used as a terror weapon against targets in the region.

- Gulf shipping could be at risk. Although we believe that Iran can’t permanently close the Persian Gulf, it could reduce oil flow for a few months and push oil prices much higher.

- There could be a more serious attack on Saudi oil facilities. Although the last attack was serious, it could have been much worse, and it is possible Iran “pulled its punch” on this attack to avoid escalation. Escalation now may be the watchword.

- We would expect a cyberattack against the U.S. and allies. Although historical analogies are never perfect, the divergent interests and interlocking relations in the Middle East is somewhat similar to Europe prior to WWI. The trigger for that war was the assassination of the Austrian archduke and his wife, caused, in part, by complicated Balkan politics. What turned a regional issue into a massive war was outside power involvement. We don’t expect outside powers to come to Iran’s aid. Although China and Russia have somewhat friendly relations with Iran, they probably won’t risk war with the U.S. to support Iran. However, we would not be shocked to see Russia, China, and maybe even North Korea support Iran in a cyberattack on the U.S. This support is possible because attribution of cyberattacks can be very difficult. Thus, these outside powers could “cover their tracks” behind an Iranian effort and act as a force multiplier. There is already evidence that Iran is taking action in the cyber theater. Researchers at cybersecurity firm FireEye and the think tank Atlantic Council say they have already found evidence that Iran has stepped up its use of social media accounts to spread pro-Iran propaganda following Soleimani’s killing.

- We would expect Israel to become a target for Iranian proxies. Hezbollah has been cautiously avoiding triggering a war with Israel; but this event may remove that caution.

- We would also expect a global assassination effort against American military, business and political officials. Historically, Iran and its proxies have been very effective in the Middle East in these efforts. They also had success in South America, some in Europe, but little in the U.S. Thus, Americans overseas are likely now targets.

- What we don’t expect is a conventional military response. Iran’s conventional military power is limited and not all that effective. Although it can’t be completely ruled out, an invasion of Iran is highly unlikely as is conventional warfare by Iran against its neighbors, excepting naval action in the Persian Gulf.

- Iraq is at the crossroads—Iraq’s underlying problem is that it was never a normal nation, but a colonial construct. For most of its history it was ruled by a Sunni minority and doesn’t have a natural basis for nationhood. The more Iran pressures Shiites in Iraq to participate in actions against the U.S., the more Sunnis and Kurds will be open to separation from Baghdad. The decision over the weekend by the Iraqi Parliament to demand the U.S. troops leave Iraq was not binding and only occurred because Sunni and Kurdish lawmakers didn’t participate in the voting. It is important to remember that the rise of Islamic State was supported by Sunnis in eastern Syria and Western Iraq and another Sunni state could emerge there if Iranian pressure becomes overbearing.

- Oil is the key risk—since the early 1980s, geopolitical oil disruptions have become relatively short term in nature. Even the Gulf War didn’t keep oil prices high for more than a few months. The memories and historic gasoline price hikes and the notorious gas station lines are fading from the collective memory as baby boomers age. We have seen a steady stream of pundits in the financial media telling us that oil is nothing to worry about. If there is going to be a problem, it will come from hoarding. Under conditions of supply uncertainty, consumers will hold oil for precautionary purposes, driving up demand and prices. If the uncertainty is high enough, it can lead to excessive price increases, well beyond what inventory levels would suggest.

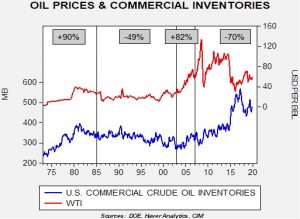

This chart shows the price of West Texas Intermediate with U.S. commercial crude oil stocks. Under normal circumstances, inventory represents the difference between supply and demand, and so there should be an inverse correlation between stockpiles and price. In other words, rising inventories should bring lower prices and vice versa. However, under conditions of hoarding, some of the inventory build represents precautionary demand and the correlation can turn positive. The chart above shows the relationship of these two variables since 1973, when OPEC became the global swing producer. Although the majority of the time the correlation is inverse, there have been significant periods of positive correlation, especially in the 1970s into the mid-1980s. In this period, unrest in the Middle East (two wars, the Yom Kippur War and the Iran-Iraq War, the Iran Revolution) led to constant fears of supply shortages and hoarding behavior. We also saw a short period of positive correlation from 2003-07, on “peak oil” fears and the rapid rise of Chinese oil demand.

The West has several tools available to dampen hoarding activity. First, the OECD nations and China have strategic reserves which, in theory, can be used to distribute supply globally to dampen hoarding. Second, the rise of U.S. shale production has created an important supply buffer outside the Middle East, where the vast majority of OPEC’s excess oil capacity resides. These may be enough to prevent hoarding. However, there is potential that these two factors may fail to prevent the hoarding instinct. First, the strategic reserves work because in a crisis, the OECD, through the IEA, would take control of national strategic reserves; in other words, the IEA could demand the U.S. sell oil to Panama from the U.S. SPR. This program has never actually been executed, but in the current nationalist environment, we think the odds of U.S. taxpayer provided oil being sold outside the U.S. to prevent hoarding in Central America is extremely unlikely. Second, the shale oil supply only dampens hoarding if it is available for export. In the case of a supply emergency, the temptation to close off American oil exports will be very high. Thus, WTI prices might stay low relative to world prices, but global prices, represented by Brent, might soar. The potential for oil prices disrupting global economic growth is probably as high now as it was in the 1970s. And so, the “playbook” of assuming that geopolitical events in the Middle East only have a short-term impact on oil prices, the pattern seen since 1985, may not be as operative as the parade of analysts on the financial media seem to think.

- S. is going mostly alone–British Prime Minister Johnson, German Chancellor Merkel and French President Macron issued a joint statement calling for de-escalation of the U.S.-Iran conflict. After U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo complained that the Europeans weren’t being supportive enough following the assassination of Iranian Revolutionary Guards General Soleimani, British officials offered tacit approval of the U.S. action. All the same, reports indicate the British were given no advance warning of the assassination. We suspect they found that perturbing, as it meant they couldn’t move their hundreds of troops and contractors in Iraq out of harm’s way beforehand.

China-Hong Kong: The Chinese government replaced its top representative in Hong Kong with Luo Huining, a former provincial leader who is expected to be tougher on the city’s continuing anti-China protests. Even though Beijing’s many similar baby steps haven’t led to a bloody confrontation, or clampdown yet, such a move is likely to keep alive the risk of such an outcome, so it will probably be negative for Hong Kong stocks.

Trade: It appears that Phase One of the U.S./China trade deal will be signed in Washington on January 15. Boris Johnson wants to “fast track” a deal with the EU to get a trade deal done before 2021.[1] France is warning the U.S. not to retaliate against its digital tax.

Venezuela: Opposition leader Juan Guaidó, who as head of the National Assembly declared himself interim leader of the country last year, was voted out of his legislative role and replaced by opposition deputy Luis Eduardo Parra. Ahead of the vote, police prevented Guaidó and his supporters from entering the legislative building, prompting U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo to accuse President Maduro of orchestrating the vote through an “undemocratic campaign of bribery and intimidation.” Guaidó’s supporters then held an impromptu vote to re-elect him, but it is not clear whether he will retain the confidence of the country’s anti-Maduro forces. We would score this as at least a short-term win for Maduro that will prolong Venezuela’s misery.

Turkey-Lebanon: President Erdogan said Turkey has already started sending soldiers to Libya to help its UN-backed government fend off rebel attacks, in defiance of President Trump’s call last week for Turkey to stay out of the conflict. Erdogan insisted the Turkish troops would have no direct combat role, suggesting their Syrian militia allies would lead the fighting.

India: In a sign that Prime Minister Modi’s Hindu nationalist movement is gathering force, a mob of Hindu rightwing activists stormed India’s most prestigious secular academic institution, Jawaharlal Nehru University, and commenced beating students and faculty members they accused of being insufficiently nationalist. It’s not clear whether the storming was sanctioned, or organized by Modi’s Hindu nationalist government, or whether it was spontaneous. In either case, accumulating incidents like this point to a potentially destabilized social situation that could eventually be negative for Indian stocks.

Global Cocoa Market: In devastating news for the world’s chocolate lovers, the West African countries of Ivory Coast and Ghana have agreed to form a cocoa cartel and will try to boost the price of the main ingredient of chocolate to $2,900 per ton from the current $2,500 per ton. Together, the two countries produce almost two-thirds of the world’s cocoa, so market participants are anticipating prices will rise substantially.

[1] See what we did there?!