Daily Comment (August 12, 2019)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] It’s an August Monday. Equities are under pressure again this morning and risk assets, in general, are weaker. Here is what we are watching:

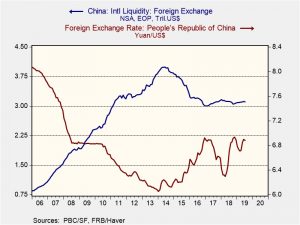

China and the dollar: For the third consecutive day, the PBOC fixed the CNY/USD exchange rate above 7. Although this reference rate was a bit stronger than Friday’s level, it suggests PBOC policy is more about stabilizing the exchange rate at a point weaker than 7 (the higher the rate, the weaker the CNY). There are two reasons why the PBOC probably isn’t letting the CNY sink lower. First, there is the constant problem of capital flight. During previous periods of CNY weakness, foreign reserves fell as Chinese investors moved money out of the country to protect themselves from a depreciation.

This chart shows foreign reserves and the CNY/USD exchange rate. The CNY began to weaken in early 2014. From 2014 to late 2016, the currency weakened nearly a full CNY and foreign reserves fell by nearly a trillion dollars. Some of the decline in reserves was due to valuation changes but there were notable levels of capital flight. China has measures to prevent capital flight but, as the data shows, regulators’ ability to prevent it is limited. The second issue, as we noted last week, was the high level of dollar-denominated debt in the private sector. There are reports that private Chinese companies are being forced to sell off foreign assets because they face a shortage of dollars. There is some debate among analysts as to what this dollar shortage means. One possibility is that the above chart’s $3.1 trillion of dollar assets is not liquid or is already committed. In other words, these companies may be facing a real dollar shortage and China may be in bigger trouble than it appears. The second explanation is that China has ample dollar reserves but doesn’t want to spend them on the private sector. Allowing (forcing?) private companies who splurged on foreign buying (which may have been related to capital flight) may be in Beijing’s best interest. The leadership may want to discourage Chinese companies from buying assets overseas and warn foreign lenders that lending to private Chinese companies, even big ones, is riskier than it looks. We tend to think the second explanation is more likely. There has been a clear bias toward the state-owned enterprises (SOE) under Chairman Xi, and “starving” the private sector’s demand for dollars while allowing access for the SOEs would fit that partiality. Still, the reason there is a debate at all is due to the opaque nature of China’s reserve management; it is possible that the first explanation is correct and, if it is, China could be quite vulnerable to market volatility.

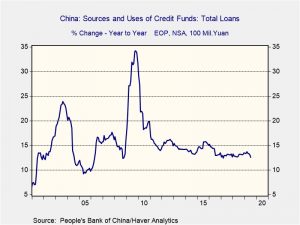

China’s lending slows: Chinese lending in July came in weaker than expected. Total loan growth slowed under 13% as the PBOC tries to rein in lending.

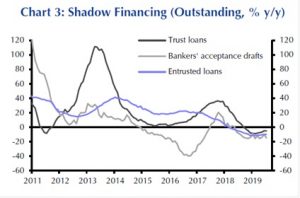

The slowdown highlights the problem Chinese authorities are facing, something similar to what the U.S. saw in 2011-13. Although monetary policy itself suggests easing, regulatory constraints are hampering the transmission process. Essentially, the entities that China wants borrowing from aren’t doing so and the firms that need the liquidity are being restricted. For example, components of private financing, or “shadow banking,” are down for the year.

In other words, China wants to see more borrowing but only by certain borrowers. If this bias continues, monetary stimulus will likely disappoint.

Authoritarians under pressure: Hong Kong remains a tinderbox as protests continue. Air traffic was halted due to unrest as thousands of demonstrators flooded terminals. Protests continue in the city as well. Beijing is escalating its rhetoric, calling it “terrorism,” which may be laying the groundwork for a military crackdown to restore order. Meanwhile, there were massive protests in Moscow, dwarfing those of previous weeks. Although the bulk of the unrest remains in Moscow, there is evidence of smaller actions elsewhere. One source of trouble for Putin is a disappointing economy. With Hong Kong, the protests there could trigger a Tiananmen-style response. If that occurs, capital flight would soar and relations with Taiwan would harden. In terms of Russia, we expect Putin to remain in control but the fact that protests are happening at all suggests his power is under pressure. In another interesting sidelight, a massive munitions explosion last week apparently caused a radiation leak, raising speculation that the blast involved a nuclear cruise missile project. If so, this is yet another setback in Russia’s military technology.

Italy: It is still unclear whether the government will fall, but the uncertainty isn’t helping Italy’s perilous financial situation as it faces credit downgrades. Salvini had to deny that his party wants to exit the Eurozone; such talk would lead to further capital flight and more downward rate pressure on German Bunds.

Brexit: There is growing talk that MPs may not be able to stop PM Johnson from a hard Brexit if he is determined to go that path. It is starting to look like the available measures of no-confidence will probably backfire and may deny MPs any role in halting a sudden exit.

Argentina: In a sign that populism may be returning to Argentina, Alberto Fernández of the Peronist party won the nationwide primary election over the weekend by a far larger margin than expected. Fernández, whose wife is former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, received 47.0% of the vote, while the current pro-business president, Mauricio Macri, won just 32.7%. Investors probably fear the return of the Peronists’ radical, unorthodox economic policies under Fernández and Kirchner, so Argentine assets will likely come under pressure in the coming days.

Deep thoughts: With fond memories of Jack Handey, here are some broader items that caught our attention over the weekend:

- The waning superpower problem: The FT ran a long thought piece about what happens to the world if the U.S. becomes less involved. We have been discussing this issue for some time; our take is that Americans were sold the policy of containing communism to foster participation in the hard work of hegemony. But, in reality, containing communism was only a small part of freezing other global conflicts worldwide. When communism fell, most Americans believed we could end the hegemonic role without realizing that a world without a hegemon is a world at risk of WWIII. We found the comment section from the aforementioned FT article to confirm that position.

- Other kinds of inflation: Although price inflation remains sticky, firms will try to maintain margins in other ways. Showrooms may have fewer sales staff; dining rooms may be less clean. Sizes may shrink. If tariffs bite, we would expect more tactics like this to maintain margins and price levels.

- The long expansion: One characteristic of this expansion is that most of the benefits have accrued to a few major metropolitan areas. Much of the rise in growth has not found its way into the rest of the country. That may be starting to change. As the cost of living in the supercities becomes onerous, there are reports that some areas of the country are seeing a secondary boom as people leave the “hot” areas for parts of the country that are more affordable. If this is the beginning of a trend, policymakers will likely try to support it by keeping policy more accommodative.