Asset Allocation Weekly – The Supply Side Worry on Inflation (September 24, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

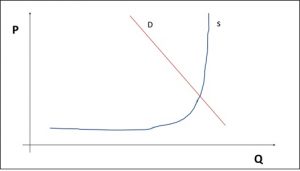

In the 1970s, the U.S. had a serious inflation problem. By the end of the decade, it had become the most critical economic policy issue. Although inflation can be a complicated topic, one way of simplifying it is to see it through the intersection of aggregate supply and aggregate demand.

On this stylized graph, prices levels are rising. In the short run, the most common way to address price levels would be to engage in austerity policies, e.g., raising interest rates, increasing taxes, reducing spending. However, that outcome also reduces output, meaning growth declines.

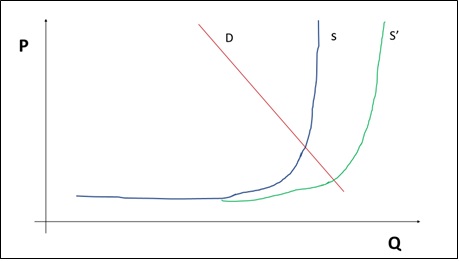

In the late 1970s, President Carter started implementing deregulatory policies. The goal was to affect the supply side. By expanding supply, price levels would decline and output would rise.

The supply side policies of the Reagan/Thatcher revolution were mostly deregulation and globalization. Deregulation allowed for the rapid introduction of new techniques and new technologies. Globalization naturally expanded the available supply. Both undermined the power of labor to push price increases into the economy.

The recent rise in inflation raises questions about the future path of prices. The FOMC maintains that inflation will be “transitory.” Although the actual definition of the word, at least in the context of policy, is “fuzzy,” it does appear that the rise in prices will moderate at some point.

Our concerns are twofold. First, using the second graph, we would argue that the supply situation has moved from S’ to S. Supply chains have been disrupted and supply will remain tight until they are repaired. However, the degree to which inflation is transitory may depend on how these supply chains are fixed. It is important to note that globalization relies on a functioning hegemon that provides global security and a reserve currency. America’s standing as a hegemon has become less certain as Americans appear less willing to engage in the sacrifices required to maintain the role. If that is the case, a return to S’ is less likely.

Another factor is tied to deregulation. In the 1970s, there was clear under-investment and malinvestment. The “rust belt” occurred to reduce the malinvestment that had emerged. To make new investment, saving had to rise and the most effective way to increase saving is to lower taxes on upper income brackets. Although overall saving doesn’t necessarily rise, it becomes concentrated in fewer households which makes it easier to concentrate investment in a similar fashion. However, over time, deregulation has tended to create industry concentration. Concentrated industries may hamper the expansion of supply.

Under conditions of competition, extraordinary profits tend to attract new entrants into the industry. As new entrants enter the market, individual firm profits eventually decline. In addition, the expansion of competition makes it difficult to raise prices. Competition acts as a break on inflation; if higher costs affect the industry, it may simply end up causing a decline in profit margins. But, with concentration, the ability for new competition to enter the market may be thwarted. Consequently, profits may persist. An oligopolist or monopolist might not increase capacity under high prices and may instead just simply accept elevated profitability.

The economic term for this is “market failure,” where the market fails to deliver the best outcome for society. In the 1970s, the supply constraints came from the lack of incentive to invest. Taxes were too high, and regulation increased costs and discouraged investment as well. Our current situation appears to be different. As the world deglobalizes, prices will rise as supply tightens. Ideally, this increase in price levels will trigger a supply response; however, if industry is overly concentrated, the response may not occur to the degree required.

It is too early to tell whether this is the situation we are facing, but the longer transitory price levels remain elevated, we have to entertain the notion that a period of higher inflation may be upon us. We still don’t see signs that we are returning to the 1970s—labor power is still too weak, and inequality favors muted inflation. But just because we are not seeing circumstances that resemble the 1970s, it doesn’t mean we are going to see inflation levels consistent with the last two decades.