Asset Allocation Weekly (March 19, 2021)

by Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

When discussing the fiscal deficit in a meeting with then-President Bill Clinton and his Council of Economic Advisors, Chief Strategist James Carville was quoted as saying, “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.” As Carville suggested, rising 10-year T-note yields are currently shaking investor confidence in global stocks, particularly in the Technology sector. The primary concern for investors is that the next stimulus package could spark inflation over the next couple of years. In this report, we discuss why some of those fears may be misplaced.

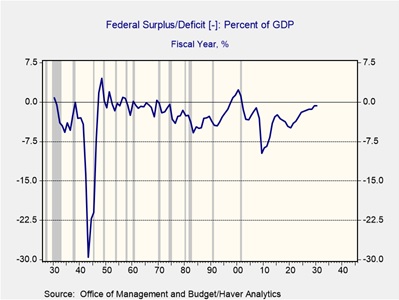

The 10-year T-note yield has tripled from 0.51% last August to a little over 1.54% today. The surge in yields can be partly attributed to fears of accelerated inflation due to the federal government’s growing deficit. The new COVID-19 relief plan has drawn the ire of bondholders because they suspect it was bigger than necessary. The prospect of higher borrowing costs hurts equities because it lowers valuations. In other words, higher yields tend to depress P/E multiples.

In general, the relationship between fiscal deficits and inflation is not all that strong. Over the last 20 years, the U.S. budget deficit relative to GDP has been the largest during any period of peacetime. Throughout this period, however, inflation has never reached the levels seen in the 1970s and 1980s. In fact, core CPI for the last 20 years has grown around the Fed’s 2% target. The two primary drivers of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) have come from healthcare and shelter. Composing nearly 40% of the index, prices in these two sectors have consistently outpaced the overall index.

Inflation has been relatively muted over recent years because the conditions that allowed it to thrive in the 70s and 80s no longer exist today. Deregulation, globalization, and lower taxes have made it easier to cut costs, while making it difficult for firms to raise prices. Deregulation and globalization have made it easier for firms to outsource labor and remove costly regulations, while lower taxes incentivized firms to adopt cost-saving technologies. Additionally, increased competition meant that only companies with differentiated or specialized goods had any real pricing power. As a result, the prices for goods such as apparel and vehicles have been roughly unchanged over the last 20 years.

Instead of seeing inflation in goods and services, we suspect that deficit spending will likely find its way into financial assets. Government spending is paid for through the private sector (which includes businesses and households) and foreign savings. Much of those savings so far have come from households as higher levels of unemployment have deterred spending. These savings have been used to pay down debt and invest in equities (cue the Reddit army). Foreign savings will likely also pick up in the coming months as consumers begin to spend more. This should be supportive of financial assets as a rise in imports is generally funded by an increase of flows into the capital account.

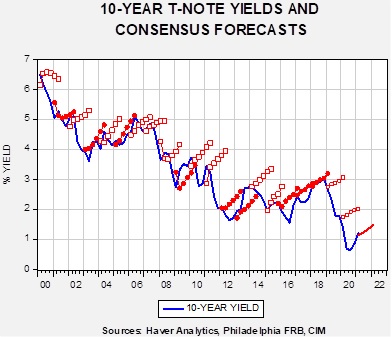

Nearly every president since Nixon has governed with an eye on the bond market. That is because bondholders overestimate the impact that new presidents will typically have on the economy. The chart above shows the 10-year T-note yield along with the first quarter forecast for the next six quarters from the Philadelphia FRB’s survey of professional economists. When the forecast is generally correct, we mark it with dots; when in error, we use open boxes. In 12 of the past 20 years, the expectation has been for rising rates and has been incorrect. Thus, investors should be aware that expectations lean toward higher rates but are wrong more than half the time. Another way of thinking about the recent rise in rates is that most of the time, the consensus is that long-duration interest rates will rise. That being said, we suspect the rise in current rates probably won’t exceed 2% on the 10-year T-note and equity markets will be able to manage this level of increase.