Asset Allocation Weekly (June 26, 2020)

by Asset Allocation Committee

(N.B. Due to the Independence Day holiday, the next report will be issued on July 10, 2020.)

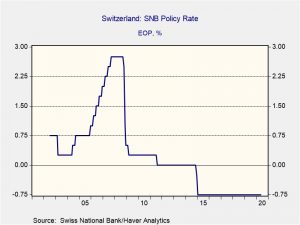

Since 2008, some central banks have implemented negative policy interest rates. Standard economics suggests that negative nominal rates on deposits are impossible because holders could simply liquidate the deposit and “put the money under the mattress.” We have observed that there are costs to holding cash in large amounts, so banks can implement a negative rate (perhaps best thought of as a fee) on holding cash. Although there are limits to how low negative rates can go (at some point, the cost of providing safekeeping exceeds the benefits), we note the Swiss National Bank has had a policy rate of -0.75% since December 2014.

Why would a central bank consider implementing a negative policy rate? If economic conditions warranted easing and inflation was low,[1] it may be impossible to use low but positive interest rates as a policy tool. In that case, negative interest rates or some other unconventional monetary policy may be necessary.

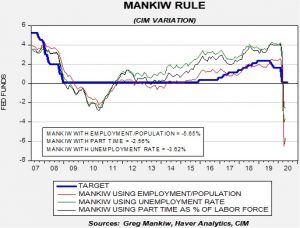

Are conditions similar in the U.S.? Our analysis of the policy rate, using the Mankiw Rule, a variation on the Taylor Rule, suggests that the FOMC could consider negative policy rates. The Taylor Rule is designed to calculate the neutral policy rate given core inflation and the measure of slack in the economy. John Taylor measured slack using the difference between actual GDP and potential GDP. The Taylor Rule assumes that the Fed should have an inflation target in its policy and should try to generate enough economic activity to maintain an economy near full utilization. The rule will generate an estimate of the neutral policy rate; in theory, if the current fed funds target is below the calculated rate, the central bank should raise rates. Greg Mankiw, a former chair of the Council of Economic Advisors in the Bush White House and current Harvard professor, developed a similar measure that substitutes the unemployment rate for the difficult-to-observe potential GDP measure. We have taken the original Mankiw Rule and created three other variations. Specifically, our models use core CPI and either the unemployment rate, the employment/population ratio, involuntary part-time employment or yearly wage growth for non-supervisory workers. In this report, we are not using the wage growth variation because it is yielding a sharply positive policy rate; wages have increased because lower paid workers have been laid off in greater numbers than higher paid workers.

As the recession developed, the unemployment rate jumped, the employment/population ratio fell, and the number of involuntary part-time workers rose. Complicating matters further, inflation declined. All these factors pointed to the need for policy stimulus. In fact, in the worst case, the employment/ population ratio variation, the nominal rate should be as low as -5.65%.

In 2008 through most of 2011, these variations of the Mankiw Rule suggested the policy rate should have been below zero. That is the case today. So far, the FOMC has rejected a negative policy rate and instead relies on expanding the balance sheet and forward guidance. The current program of balance sheet expansion is historically unique; for the first time, we are seeing the Fed buy an assortment of financial assets that expose it to credit risk. These include corporate and high yield bonds. As we noted last week, the current QE is reducing credit spreads, but, like forward guidance, the actual stimulative impact is uncertain.

So, why is the FOMC opposed to negative interest rates? The most likely reason is the structure of the U.S. financial system. The U.S. system has an extensive non-bank financial system; unlike banks, this system isn’t funded by deposits but by repo and money markets. The non-bank financial system, also known as the “shadow banking system,” finances large swaths of the U.S. economy. Although it is difficult to estimate the size, there are reports it may be as large as $1.2 trillion. The fear is that negative deposit rates would likely cause the money market funds to “break the buck” to account for the below-zero yield. That could lead to difficult-to-determine outcomes, but it is plausible that the non-bank financial system may find itself without a source of funding. Since there is no Fed backstop to the non-bank financial system, there could be a run on the loan providers. Other nations have much smaller non-bank systems and thus can manage negative policy rates. The U.S. probably can’t.

And so, additional policy stimulus, if necessary, will come from further expansion of the balance sheet and forward guidance. Another possibility would be yield curve control, which was implemented during WWII into the early 1950s. In this policy, the Fed will set the desired rate of some or all of the Treasury curve, absorbing all the Treasury borrowing that the market won’t buy, thus fixing the interest rate. The Bank of Japan and Reserve Bank of Australia are currently running such policies. Although the FOMC hasn’t taken this step yet, it is being considered by Fed policymakers. The conclusion—monetary policy will likely remain historically accommodative well into 2021.

[1] For example, Switzerland’s May CPI was -1.3% from last year.