Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – The Hidden Battle in the “One Big, Beautiful Bill” (June 30, 2025)

by Thomas Wash | PDF

Tucked within the (ironically named) One Big, Beautiful Bill Act lies a provision that could dramatically reshape international capital flows. Section 899, colloquially termed the “revenge tax,” would empower the federal government to impose escalating taxes on the US passive income of individuals and corporations in countries with tax policies deemed discriminatory against American firms. This retaliatory tax, starting at 5% and potentially rising to 20%, represents a significant escalation in financial protectionism that could have far-reaching consequences for global markets.

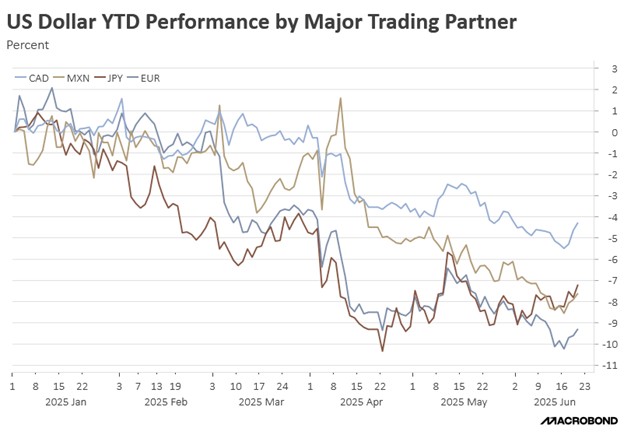

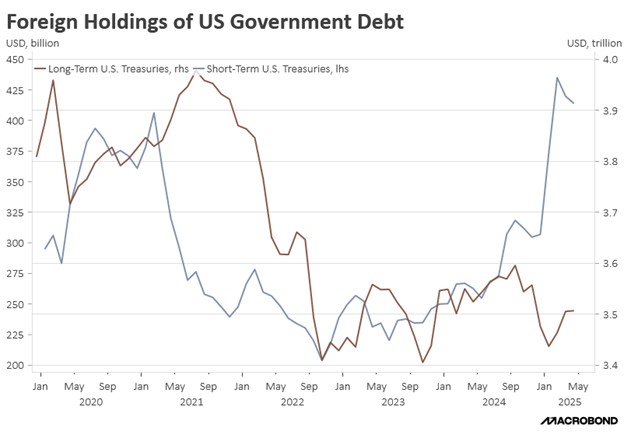

Approximately $25.7 trillion in foreign-held US assets could potentially be affected. This includes $18.5 trillion in US equities (representing 20% of the market) and $7.2 trillion in Treasury securities (30% of the market). By taxing capital income going to foreigners, this provision risks weakening the demand for US Treasurys and could potentially trigger capital flight. The timing is particularly concerning as recent trade tensions have already sparked worries about the US dollar’s role as the global reserve currency. Substantial capital outflows could significantly increase the US’s borrowing costs and undermine the dollar’s global dominance.

The legislation specifically targets foreign policies that US lawmakers view as discriminatory, including the OECD’s two-pillar global tax framework (particularly its Undertaxed Profits Rule), various unilateral diverted profits taxes, and the EU’s Digital Services Tax. Washington considers these measures extraterritorial overreach that threatens US fiscal sovereignty while disproportionately harming American firms. The provision reflects populist concerns that foreign governments and supranational organizations are teaming up against US corporate interests in violation of established international norms.

Drawing inspiration from the reciprocal tariff measures unveiled in April, this legislation introduces a coercive framework that is designed to compel foreign governments to either rescind tax policies deemed discriminatory by the US or incur financial penalties. Republican lawmakers assert that certain OECD and eurozone tax initiatives fundamentally contravene core provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), thereby creating direct conflicts with America’s established international tax framework. Specifically, the conflicts in question are with (1) Global Intangible Low-Taxes Income’s (GILTI) anti-profit-shifting rules, (2) Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax’s (BEAT) anti-base erosion protections, and (3) Foreign-Derived Intangible Income’s (FDII) innovation incentives. Consequently, the revenge tax functions as both a punitive instrument and a defensive mechanism.

If Section 899 is included in the final legislation, the US technology sector may emerge as a significant beneficiary. With major US tech firms deriving 40-60% of their revenue from overseas, the threat of retaliatory taxes could pressure foreign governments to reduce their own levies on American companies. This potential upside, however, must be weighed against broader market concerns such as weaker demand for US-denominated assets, which could push up Treasury yields and reduce the attractiveness of US equities. In turn, those developments could slow the economy and weigh further on the dollar, although one benefit would likely be a narrowing of the US trade deficit.

Senate negotiators are working to modify the most controversial elements of Section 899, including clarifying the status of Treasury securities and potentially lowering initial tax rates. But the administration’s track record of aggressive policy implementation has left many investors skeptical of verbal assurances. As the bill progresses, global markets will be watching closely to see whether this represents a strategic recalibration of US economic policy or a potentially destabilizing shift in international financial relations. The ultimate impact may depend on how foreign governments and investors respond to what could be interpreted as a new era of financial nationalism.