Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – No Country for Recessions (August 4, 2025)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

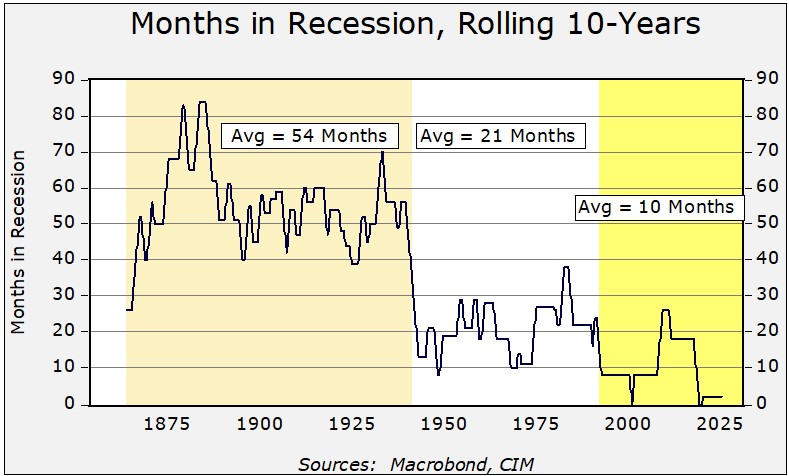

Recessions in the United States have become less frequent over time. To illustrate this, the chart below shows data from the National Bureau of Economic Research, the official arbiter of recessions in the US, which has been establishing business cycles since January 1854. In the chart, we show the total months spent in recession over a rolling 10-year period. Clearly, we have seen the incidence of recession decline over time. From 1864 until 1940, recessions occurred, on average, 54 months out of 120 months, or 45% of the time. From 1941 to 1991, the average declined to 21 months, or 18% of the time. Since 1991, the average fell to 10 months, or 8% of the time.

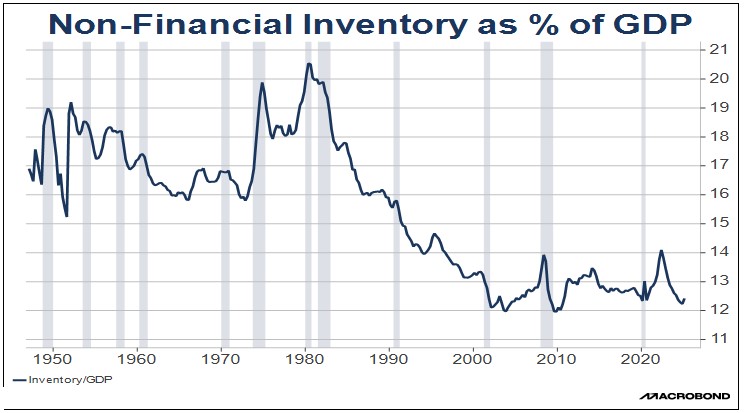

Why has the incidence of recessions declined? There are three primary reasons. First, as the economy evolved into being dominated by services instead of manufacturing, there were less inventory misallocations causing slumps, especially after 1980. As shown in the next chart, inventories relative to gross domestic product (GDP) have clearly fallen. Therefore, the likelihood of excess inventories or other issues arising from misallocation of inventory also fell.

Second, until the 1930s, recessions were thought to be natural occurrences. Often, the burden of policies that allowed recessions tended to fall on debtors and the lower classes, who had limited political influence. After WWI, this idea became contested and was one of the reasons for the unraveling of the gold standard. Because the gold standard created inelastic conditions for liquidity, central banks were restricted from easing credit conditions during downturns, leading to deflation. After WWII, monetary and fiscal policy became countercyclical; in other words, policies were designed to either prevent or mitigate recessions. By the mid-1990s, monetary policy transparency became the norm, further reducing the amount of policy shocks.

The third factor behind less-frequent recessions is the expansion of globalization that started in 1978 with deregulation and accelerated after the end of the Cold War. The rise of globalization increased the available supply, which led to lower inflation and a decline in interest rates. This period, dubbed “the great moderation,” made it easier to extend the business cycle.

This history raises two questions. First, will this period of infrequent recessions continue? And second, what are the ramifications if it does? Addressing them in order, it’s likely that infrequent recessions will continue because two of the three conditions described above should remain in place. We expect that services will continue to dominate the economy, while modern inventory management will maintain stability. At the same time, countercyclical policy isn’t likely to change. If anything, policy accommodation appears to be expanding (raising inflation concerns). In our view, only the third condition for less-frequent recessions will be less supportive. As the US attempts to rebalance the global trading environment, imports will become less plentiful, and the potential for supply shocks will rise. Of course, as domestic production responds, the potential for foreign-driven supply shocks (as observed during the pandemic) will also be less of an issue. But overall, the trend toward fewer downturns looks to be in place.

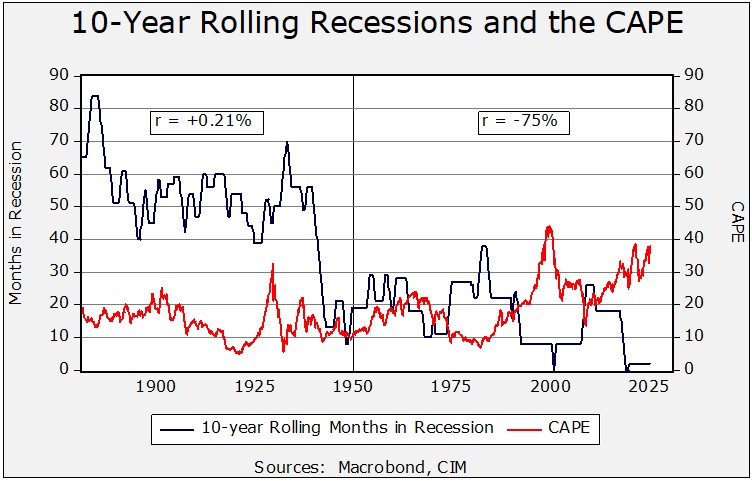

What does this mean for equity markets? Less frequent recessions, at least in the postwar period, correlate with higher price/earnings multiples. We show this in the chart below, which overlays the rolling decades of recessions with the Shiller cyclically adjusted P/E ratio. From 1870 to 1950, the correlation was low and positive. However, since 1950, the correlation has increased significantly and turned negative. In other words, the declining occurrence of recessions is now associated with higher stock valuations.

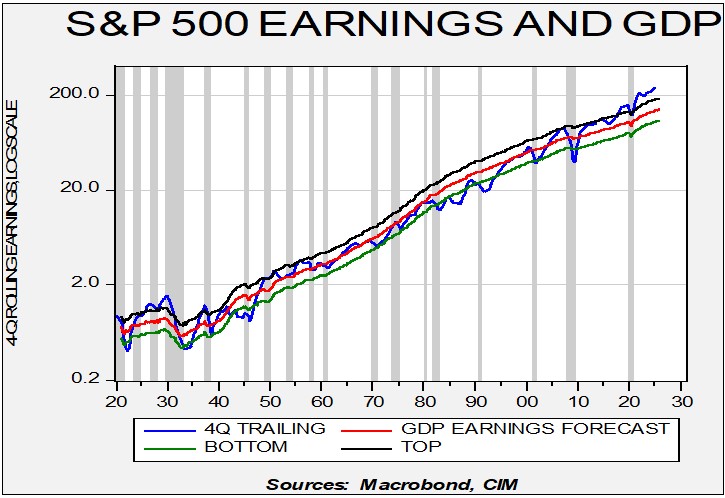

Finally, the chart below shows S&P 500 earnings on a four-quarter rolling basis compared to a regression of earnings to nominal GDP. Recessions are indicated by the vertical grey bands. The chart shows that, in the postwar era, recessions tend to depress earnings. Thus, if recessions remain less frequent, it makes sense that the earnings multiple would be higher. Investors generally can worry less about economic downturns, giving them greater confidence to bid up stock values relative to earnings.