Daily Comment (January 31, 2017)

by Bill O’Grady, Kaisa Stucke, and Thomas Wash

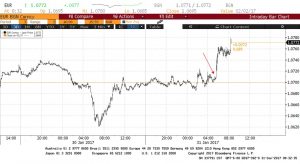

[Posted: 9:30 AM EST] There was a lot of political news overnight but it didn’t have much impact on financial markets. However, this morning, Peter Navarro, the director of the newly formed National Trade Council, told the FT that Germany is using a “grossly undervalued” exchange rate to “exploit” the U.S. and its EU trading partners. The EUR rose on the news, indicated by the red arrow on the chart below.

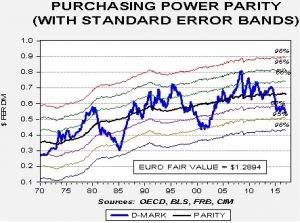

In terms of his analysis of the euro, we tend to agree with him. Here is our parity model of the euro, using German and U.S. consumer inflation.

Purchasing power parity uses relative inflation to value exchange rates. The theory is that in a freely floating environment, the exchange rate should move to equalize prices between nations. So, if cars in Canada are cheaper than in the U.S., Americans would buy Canadian cars but the demand for Canadian dollars would rise as a result and the exchange rate would appreciate to eventually equalize the exchange rate-adjusted prices between the two countries. Simply put, the lower price levels are in a nation, the stronger its exchange rate. In reality, it’s only a guide to exchange rate valuation. For example, not all goods in a consumer price index are tradeable, so relative inflation rates are not perfect proxies for exchange rate valuation. Trade isn’t frictionless, so deviation in the price of goods can persist even if tradeable. And, financial factors, such as interest rates, may overwhelm inflation. However, at extremes, the measure has some value.

The model suggests the D-mark is trading almost two standard errors from the forecast, or around 18% undervalued relative to the dollar. There have only been two other periods when the dollar has been this strong relative to the D-mark, in the mid-1980s and at the turn of the century. Eventually, the exchange rate reversed.

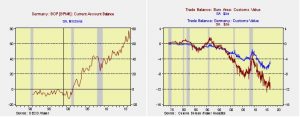

Navarro’s claim that Germany manipulates its currency also has merit (although technically it’s Europe’s currency, in reality, Germany effectively controls it because of its economic dominance over the Eurozone). Germany has traditionally suppressed consumption and boosted saving, macroeconomic policies designed to bring trade surpluses. Until the introduction of the euro, Germany was typically prevented from expanding its trade surplus due to D-mark appreciation. However, now that it uses the euro, its European trading partners can’t use depreciation to remain competitive. Since the euro was introduced, Germany’s current account (trade surplus plus official and private remittances) has ballooned.

These charts show Germany’s current account (the vertical line shows the introduction of the euro) and the Eurozone and German trade accounts with the U.S. Clearly, Germany and the Eurozone run persistent trade surpluses with the U.S. and the German current account has swelled since the introduction of the euro.[1]

Here are the complications in Navarro’s comments. First, the Treasury has the mandate for currency policy. If multiple voices start commenting on exchange rates, it will make it tricky to determine what the administration’s currency policy actually is. Second, the U.S. runs trade deficits because this is how the system is designed. As long as we are the reserve currency, other nations in the world have an incentive to adopt the same policies as Germany (and many do, including China, South Korea, Japan, etc.). The U.S. does benefit from being the reserve currency; we receive goods from the world and give dollars back that are held as savings. In fact, if these reserves are not immediately spent, those dollars are recycled back into the U.S. financial system in the form of investment, often in Treasuries. This means that foreigners give us stuff and also help fund our deficit in return for dollars; The Economist describes this condition as writing checks that nobody cashes. The downside? If one competes in an industry facing import competition, there is a fair chance one will not be working at some point. It’s hard to compete in a globalized world.

It appears the administration is figuring out that its goals of reducing the trade deficit and boosting jobs in the U.S. could be thwarted by a strong dollar. In fact, the controversial border adjustment in the GOP House corporate tax reform bill won’t be inflationary if only the dollar appreciates. So, the administration is finding itself at cross-purposes. On the one hand, it wants to create more jobs in the U.S. and is targeting import reduction as a policy to achieve that goal. However, as long as the dollar is the primary reserve currency, other nations will take steps (e.g., currency depreciation) to maintain import flows into the U.S. In fact, the more barriers we erect, the more aggressive foreign nations will become because the dollar is still the best currency to use for global trade.

Perhaps the most important person in this whole debate is Chair Yellen. If the Fed turns more hawkish on fears of inflation and fiscal expansion, the dollar will tend to appreciate. As we continue to say, we will be watching very closely to see how the president reacts to Fed tightening. If the Fed faces a strongly negative reaction from the administration, the dollar may not rally much from here. Of course, the lack of monetary tightening, a weaker dollar and trade impediments are a recipe for inflation and higher interest rates, especially on long-duration assets.

So, the FOMC meets tomorrow. Current expectations for a rate hike are only at 13%; in fact, they don’t exceed 50% until June (all based on fed funds futures). This suggests the markets are not expecting an overly hawkish statement. Stay tuned…

____________________________________

[1] For a deeper look at this issue, see this week’s WGR.