Asset Allocation Weekly (October 14, 2016)

by Asset Allocation Committee

Given continued sluggish economic growth and fears that monetary policy has reached the point where it can no longer stimulate growth, a renewed attention has been brought to discretionary fiscal policy. In the 1970s, discretionary fiscal policy fell out of favor due to a number of shortcomings:

- Public investment, if needed, should not be timed to offset recessions. In other words, if the Navy needs an aircraft carrier, one should be built without waiting for a recession. Thus, public investment should be based on need, not designed as a countercyclical policy.

- Discretionary policy must pass through the legislative process. This tends to slow the outcome to the point that the recession may have passed by the time Congress allocates spending.

- Fiscal spending, especially fixed asset spending, can “crowd out” private spending. In functioning investment markets, investment spending should be generated by cutting interest rates rather than by directing public investment by government fiat. In addition, private investment is forced to pass through the test of profitability, reducing the likelihood of malinvestment.

From the late 1970s, economists generally concluded that discretionary fiscal spending was unnecessary and that countercyclical monetary policy was sufficient to guide the economy through recessions. Although there were occasional extraordinary fiscal measures taken during some downturns, such as tax rebates and extended unemployment insurance payments, for the most part, monetary policy was the measure of choice in terms of countercyclical policy.

However, the developed world now finds itself in a situation where monetary policy may have reached its point of diminishing returns. The Bank of Japan (BOJ), the Swiss National Bank and the European Central Bank (ECB) have tried to implement negative interest rates. In these cases, it appears that the damage to the banking system is offsetting any gains from lower rates. Balance sheet expansions (QE) have been deployed by the aforementioned central banks and the Federal Reserve. In general, balance sheet expansion has become less effective; a common complaint is that asset values have been extended in many markets without generating much economic growth. Central banks are also struggling to find assets to purchase. The BOJ has been buying equity ETFs and the ECB has added corporate bonds to its balance sheet, causing further financial market distortions.

This isn’t to say that the central banks have exhausted all their options, but the ones that remain cannot be implemented without help. For example, central banks could implement quantitative easing by purchasing foreign bonds; this would likely lead to currency depreciation that would boost exports. However, such “beggar thy neighbor” policies would likely bring retaliation and further reduce global trade. The other option is “helicopter money,” which is the direct central bank financing of government spending. Although this policy would be effective, it does require the participation of fiscal authorities. In addition, central bank independence would almost certainly be compromised.

So, if fiscal policy is expanded, would we face the problems outlined above? Generally speaking, the biggest risk would be point #2 above. Getting spending plans through a divided Congress would be difficult. In addition, avoiding malinvestment, regardless of whether it’s public or private, is always hard. But in the current partisan environment, coming up with public investment that would foster future growth will be problematic. However, there is evidence to suggest that public spending has been neglected for some time and that private investment is currently weak, reducing the problem of “crowding out”; in other words, concerns about points #1 and #3 are reduced.

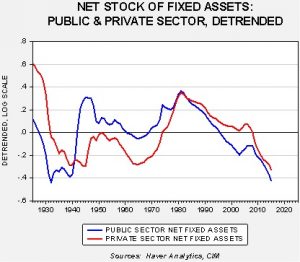

This chart shows the net stock of fixed assets for both the public and private sectors. We have log transformed the data and de-trended both series. In general, a reading over zero indicates the net stock of fixed assets is above its long-term trend and vice versa. Note that public sector assets were above trend from 1940 into the mid-1990s. This was mostly due to elevated Cold War defense spending. During this period, private sector fixed asset levels tended to remain under trend, although a surge that began in the mid-1960s did eventually lead to a rise above trend. Note that the surge of both public and private spending on fixed assets in the 1970s probably led to crowding out and higher inflation.

Current conditions suggest that both private and public sector investment are well below trend. In general, private sector investment tends to have a greater impact on future growth and would thus be preferred. However, given an environment of weak asset formation from both sectors, the economy would likely benefit from increased investment in either sector. Thus, promises of increased spending on infrastructure and defense would likely have a positive effect on the economy and be positive for equity markets.